Tony Nicklinson: The trapped man

- Published

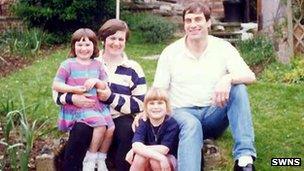

Tony Nicklinson died with his wife, daughters and sister by his side

BBC Wiltshire presenter Lee Stone got to know Tony Nicklinson during his battle for a law change that would allow doctors to legally end his life.

Here he offers his personal tribute to the 58-year-old, who died earlier.

Less than a week ago, I was sitting in Tony Nicklinson's kitchen looking at a solitary good luck card on the tidy granite work surface.

It was five minutes to 14:00 BST, and the nation's media had crammed into his modest Melksham bungalow to hear whether the High Court would let a doctor end the life that Tony described as "miserable, demeaning, and not worth living".

As it turned out, Tony Nicklinson had no luck. When two o' clock arrived and the court handed down its decision, he burst into tears.

He wept like a child, uncontrollably and without dignity.

He wept in the way most of us would weep if we were told we were going to die. For Tony, the news was worse. He was going to live.

I first met Tony Nicklinson three years ago. He had been a successful engineer who had lived and worked in Hong Kong and Dubai.

The plain walls of his small room were covered with pictures of him playing rugby, skydiving, and standing proudly with his wife and two children.

'Twisted and broken'

He sat in front of those memories, slumped in a medical chair. His body was twisted and broken after a catastrophic stroke during a business trip to Athens in 2005.

The first interview was tough. How do you talk to a man who can only answer by blinking letters to his wife so that she can painstakingly guess at what he's trying to say?

A man who makes lucid, compelling arguments while dribbling incessantly and coughing alarmingly?

It became easier as I began to understand his rather stubborn viewpoint.

After his stroke, Tony Nicklinson could only communicate by blinking

The more he told me, letter by letter, that he didn't give a hoot about what the religious lobby thought, the more I wanted to challenge his position.

And the more I wanted to challenge him, the more I began to share the frustration that he was feeling as he sat, locked into a body that simply refused to do what he asked of it.

Over time we shared emails. His were always direct and to the point. They were sharp and clear.

As months progressed, his campaign gathered pace. He became clearer about how he wanted to die.

He sent me a document which he had written, asking me what I thought about his idea for a machine which could administer a lethal injection to end his life. His life was the stuff of nightmares.

What will Tony Nicklinson's legacy be? He leaves behind a wife and two daughters who have been his fiercest advocates.

They are a family who loved him enough to be prepared to let him go. More than that, they were prepared to fight for him to go.

Seven years late, they will be able to say goodbye to the man they lost back in Athens in 2005.

But there is a sad paradox to Tony's death. His natural passing puts an end to his long campaign to take back control of his life.

Now, he will not achieve his aim of wrestling control of his life from a legal system which couldn't find a way to protect the vulnerable while allowing him freedom of choice.

Ultimately, death has robbed him of the right to die.

- Published22 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published16 August 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published19 June 2012