Tony Nicklinson: Decade since death of right-to-die campaigner

- Published

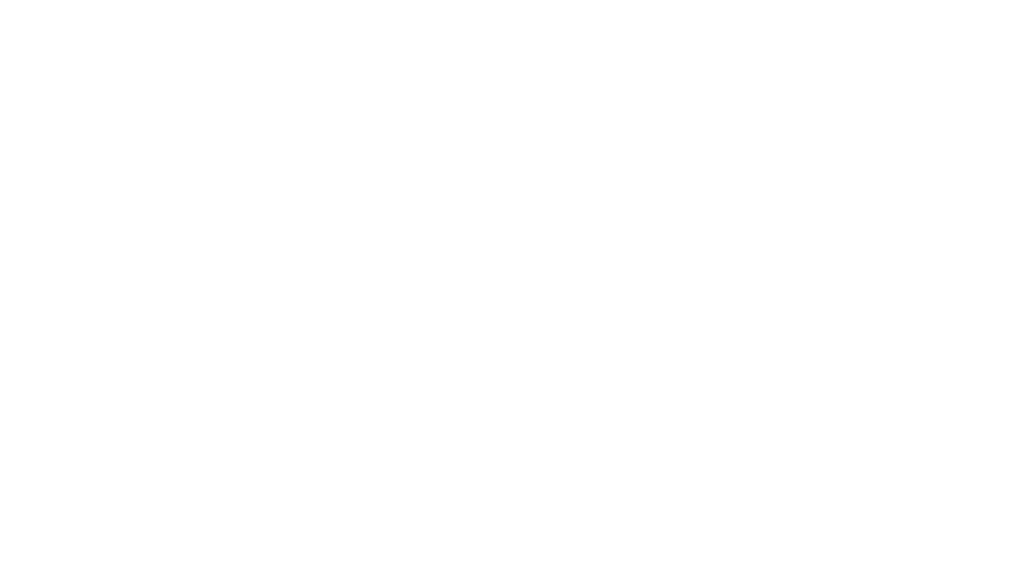

Tony Nicklinson was left with 'locked-in' syndrome after a stroke

Right-to-die campaigner Tony Nicklinson would be "angry" there has not been more progress on the issue a decade after his death, his daughter has said.

Mr Nicklinson had locked-in syndrome and fought for the right to legally end his life.

He was paralysed from the neck down after suffering a stroke in 2005. He died on 22 August 2012.

His daughter Lauren Peters, said he would be "disappointed" with the limited changes in legislation.

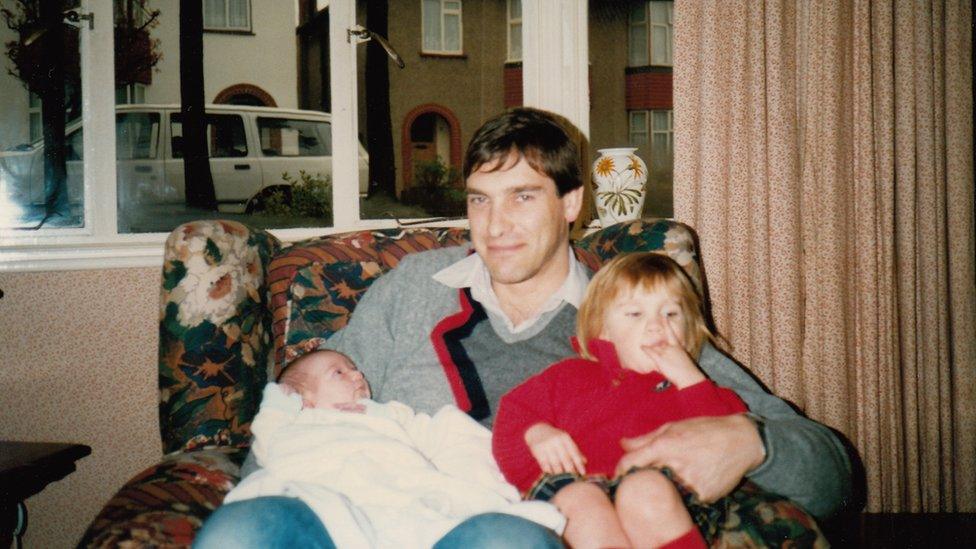

She added the family "desperately" miss her father and she knows he would have been a "brilliant" grandfather to his three grandchildren.

Mr Nicklinson, from Melksham, Wiltshire, died after refusing food not long after losing his High Court battle to allow doctors to end his life.

Mrs Peters, 35, who now lives in Bristol, said the 10-year anniversary would be a day of reflection.

She said: "One of the ways I like to deal with my grief is knowing there is meaning attached to his suffering and it is so frustrating knowing it is still not being discussed openly and is still not being addressed."

Lauren Peters, Tony's daughter lives in Bristol

Mr Nicklinson had made an advanced directive in 2004 refusing any life-sustaining treatment.

He was paralysed from the neck down after suffering a stroke in Athens while on a business trip in 2005 and described his life as a "living nightmare".

A person with locked-in syndrome is both conscious and aware, but completely paralysed and unable to speak. Mr Nicklinson could only communicate by blinking.

The 58-year-old campaigned for the law to be changed to allow doctors to assist his death without fear of prosecution.

In an article he wrote for the BBC, he said: "What I find impossible to live with is the knowledge that... I have no way out - suicide - when this life gets too much to bear.

"It cannot be acceptable in 21st Century Britain I am denied the right to take my own life just because I am physically handicapped."

Locked-in syndrome is a rare neurological disorder

Three High Court judges rejected his plea for the law to be changed, saying the issue should be left to Parliament.

His daughter, Mrs Peters, said: "There has been nowhere near enough progress, certainly not when it comes to assisted dying for those with incurable suffering.

"When we were going through our court proceedings 10 years ago, the public support we received was just phenomenal and a decade later nothing has changed and I think it still shows how cowardly our politicians are when it comes to addressing this issue.

"It will not go away, please just address it and do something."

A Ministry of Justice spokesman said: "Our sympathies remain with the families and loved ones affected by these deeply upsetting cases.

"Any change to the law in an area of such sensitivity and importance is for individual MPs to consider rather than a decision for Government."

Mr Nicklinson played a lot of rugby before his stroke

Mrs Peters added: "I think dad would be angry. Everything we did legally, everything we put into the campaign in terms of our emotion, being so upfront and open with our story - I think he'd be really disappointed to know 10 years later nothing has changed."

Trevor Moore, chair of My Death, My Decision, an organisation that works closely with the Nicklinson family, said: "We call on the Justice Secretary to set up a Parliamentary inquiry into assisted dying as soon as possible.

"Only then can decision-makers hear and test the evidence for and against - especially from those countries like Australia, Canada and New Zealand that already have a law. We owe it to Tony's family to carry forward his powerful legacy and end this grave social injustice."

Mr Nicklinson would have been a wonderful grandfather, his daughter said

Assisted Dying Bills are currently progressing in the Scottish, Jersey and Isle of Man parliaments, with votes expected in all three next year. Jersey has taken the step to say they will change their law.

Many of the attempts to change the law in England would not have helped Mr Nicklinson as they focused on those with terminal illness given six months or fewer to live, not those with incurable suffering.

Richard Huxtable, a professor of medical ethics and law at Bristol University, researches issues in end-of-life decision-making and said the difficulty revolves around the "fraught" ethics with opinions remaining "divided".

He said: "I find myself advocating a middle-ground position because I recognise strong arguments on both sides. We want to respect autonomy, we want to remove suffering but at the same time we want to protect people and lives.

"I argue we should put assisted dying in its own legal box, where we recognise it is a crime, which is an uncomfortable message, but it may be a crime for which there may be relevant, moral or ethical excuses."

Concerns have long been raised about changes in assisted dying laws by campaign groups such as Care Not Killing. It argues it would place pressure on vulnerable people to end their lives for fear of being a financial, emotional or care burden upon others.

Dr Gordon MacDonald, CEO of Care not Killing, said it could increase the instances of elder abuse and people opting for an assisted death out of depression and loneliness. He added it would undermine suicide prevention programs.

'Don't forget my dad's suffering'

Mrs Peters added she hopes people do not forget her father's suffering.

She said: "Please don't forget dad or his story. When he decided to go public, when he decided to effectively take on the government to try and achieve the death he wanted, he put so much into that, as did my mum, my sister and I - we gave a lot and at points it was tough.

"Ten years later we may have lost a little bit of relevance, but I don't want people to forget his face or what he went through. I want to know that years gone, Dad is still having an impact."

If you are affected by issues raised in this article, help and support is available via the BBC Action Line.

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published19 June 2012

- Published19 June 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012

- Published22 August 2012