A commander's story: Loss and frustration in Iraq

- Published

Bill Moore was responsible for the 19th Mechanised Brigade

When a British commanding officer was sent to Southern Iraq in June 2003, he led 4,500 soldiers into war. They were told the country had weapons of mass destruction that were a threat to international peace.

Operation Free Iraq began on 20 March 2003, when the US and UK led a coalition invasion of the country in a mission to remove its leader Saddam Hussein.

Then a brigadier, Bill Moore of Wiltshire, commanded the 19th Mechanised Brigade that operated in the provinces of Al Basra and Maysan.

"A lot of us who came back from the Iraq war, we were no longer the same as when we went away," he said.

"Some of us did not come back.

"We lost nine of the team in Iraq, many more were seriously injured. I could have changed nothing - but a sense of responsibility is something that will stay with me for the rest of my life."

By May, Iraq's army had been defeated and its regime overthrown. Saddam Hussein was later captured, tried and executed.

However, no weapons of mass destruction were uncovered.

Twenty years on Mr Moore, who was aged 44 at the time, has been reflecting on the legacy of the conflict.

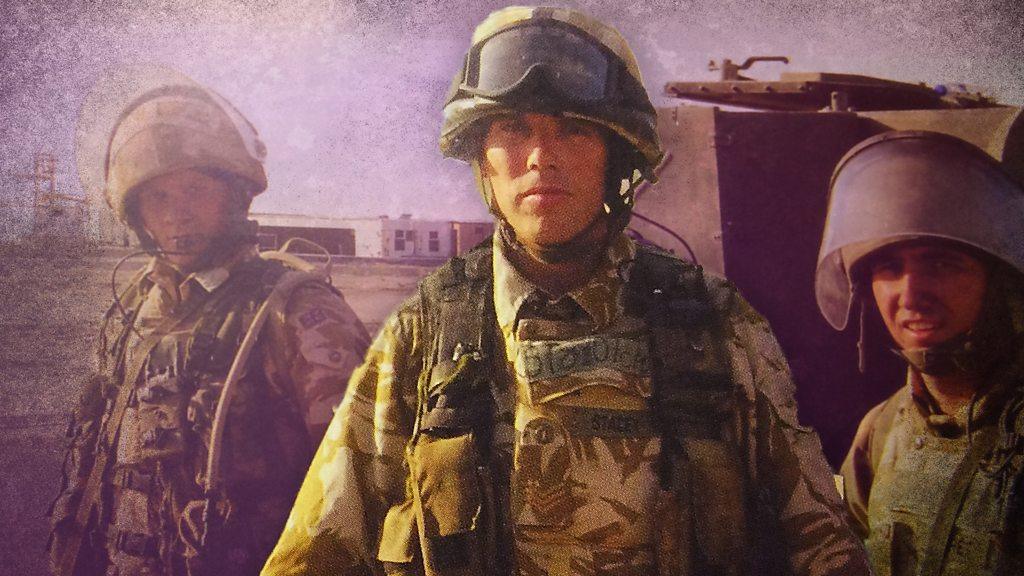

Mr Moore with some members of his team in Al Basra

When he arrived in Southern Iraq, it was the height of summer, and soldiers were operating in temperatures as high as 58C.

"There was no electricity, little water and no humanitarian aid," he said.

"People shot at us, they used mortars and made home-made bombs which became very sophisticated and could destroy our tanks.

"Our objective was to provide a secure environment so we could grow the Iraqi institutions and provide stability for the local people to thrive. But that was made very challenging."

Mr Moore said the different departments across the UK government did not work together to provide the right resources for soldiers and local people.

"There was nothing tangible in the two provinces to show the UK was committed to re-construction of Iraq," he said.

"There were no clinics staffed by British doctors and nurses, no cultural offices to engage the locals, there was no training to help Iraqi police, no teachers to help reform schooling and no local government officials to help resolve the financial crisis."

Having later been promoted to Maj Gen, Mr Moore returned to Iraq in 2009 for a joint operation with US and Iraqi Armies

Mr Moore said his brigade faced hostility from local people who did not believe the UK was serious about improving their country.

"If things are not going right in the country, people take it out on the occupying forces, not the powers behind them - so they took their frustration out on us soldiers," he said.

"There would be verbal abuse, stone-throwing, petrol-bombing, and shootings.

"It wasn't because they didn't like what we stood for, it was frustration that nothing was changing.

"Local people were fed up of not having electricity, water, jobs, and they were still living in bombed-out buildings."

Mr Moore working on joint operations alongside the Iraqi Army

Mr Moore said the lack of progress made by the government, created a situation where gaining the trust of local people was difficult.

"One thing we knew we needed to do was to try and understand the culture we were being introduced to," he said.

"I met all the key imams in the area, and also received a couple of dressing downs from them.

"I got on very well with them, they knew we were in a difficult position, but they also had their position to sustain.

"One gave me a telling off about how useless the British were, but I was hugely respectful to him, he was a religious leader.

"Later, I found out he had taped the conversation and played it to his followers, to show he had put a British commander in his place."

Mr Moore commanded 4,500 troops across Southern Iraq in 2003

But a task even more difficult was the weight of being responsible for 4,500 people, even 20 years later, Mr Moore said.

"When we left Iraq in November 2003, we felt a sense of unfinished business, despite doing the best job we could do," he said.

"I always reflect on whether it was worth it - for all the injuries and people who did not come back.

"No weapons of mass destruction were found. It is a tricky and frustrating equation to square away.

"Those soldiers and officers, they were somebody's husband or son, or sister or brother."

Sir John Chilcot's inquiry into the war found intelligence "had not established beyond doubt either that Saddam Hussein had continued to produce chemical and biological weapons or that efforts to develop nuclear weapons continued".

Prime Minister David Cameron made a statement in the House of Commons , externalon 6 July 2016 following the publication of Chilcot's inquiry report.

"Saddam had built up chemical weapons in the past - and used them against Kurdish civilians and the Iranian military," Mr Cameron said.

"He had given international weapons inspectors the run around for years.

"And the report clearly reflects that the advice given to the government by the intelligence and policy community was that Saddam did indeed continue to possess and seek to develop these capabilities.

"However, as we now know, by 2003 this long-held belief no longer reflected the reality."

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published20 March 2023

- Published20 March 2023

- Published20 March 2023

- Published19 March 2023