Calls for government to confirm Sergei Skripal was a spy

- Published

Mother-of-three Dawn Sturgess died after coming into contact with the Russian nerve agent Novichok

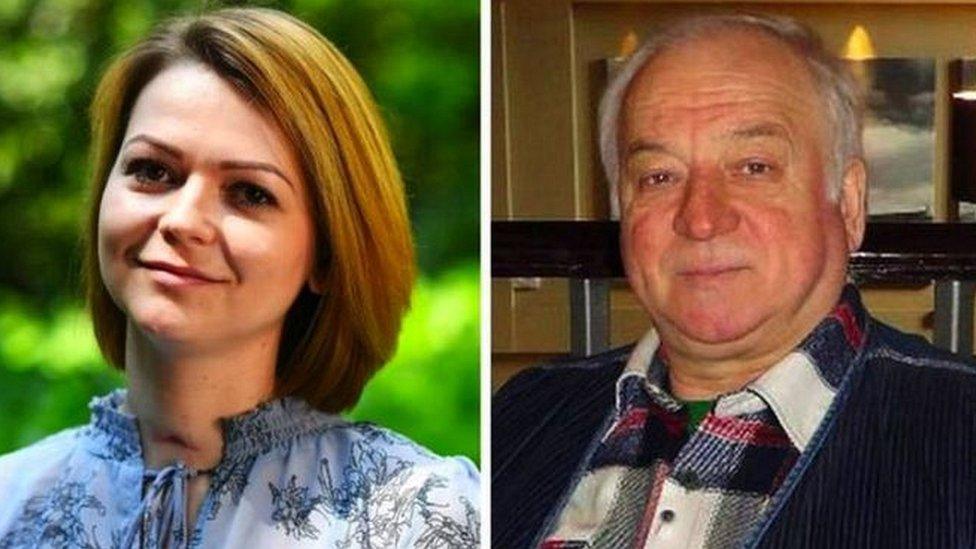

The government is facing calls to confirm that Sergei Skripal, who was poisoned by a Russian nerve agent in Salisbury in 2018, was a British spy.

The demand came in a preliminary hearing of the public inquiry into the death of Dawn Sturgess, who died after coming into contact with Novichok.

Barristers for Ms Sturgess and her partner Charlie Rowley said the link had already been widely reported.

A barrister for the government said confirmation could put people at risk.

Ms Sturgess died in hospital on 8 July 2018 after she was exposed to Novichok, which had been stored in a discarded perfume bottle found by Mr Rowley and given to her as a gift.

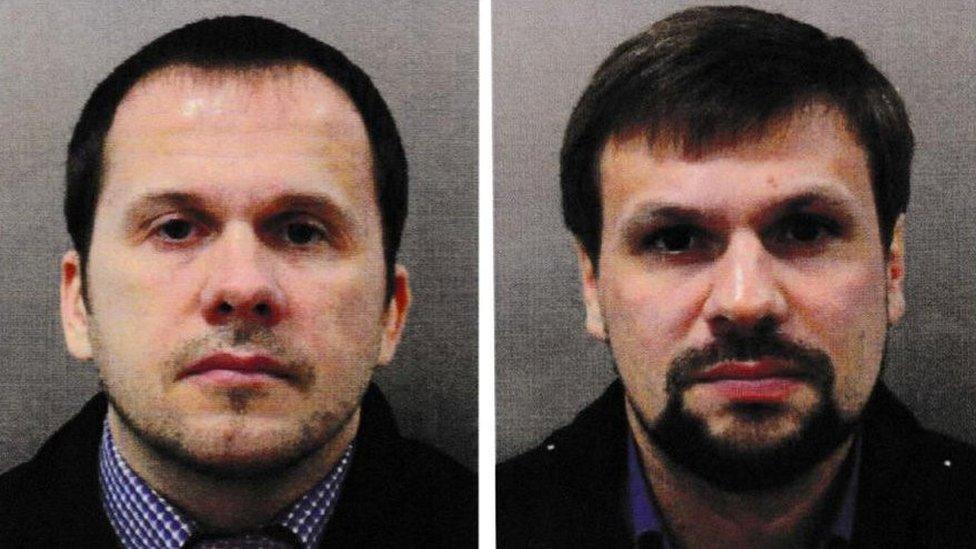

It followed the attempted murders of Mr Skripal, his daughter Yulia, and ex-police officer Nick Bailey, who were poisoned in Salisbury earlier that year in March.

The previous inquest into Ms Sturgess' death was converted into a public inquiry to allow it to have access to top secret intelligence that will be considered in private.

Chairman of the inquiry, Lord Hughes, said on Wednesday it was inevitable there would be "perhaps quite a lot" of material kept secret from the public.

Lord Hughes said that although the starting point would be for everything to be heard in an open hearing, issues of national security and police workings would have to be heard in private.

He described it as "immensely frustrating" for those who can only attend public hearings.

Acting on behalf of Ms Sturgess' family, Adam Straw KC argued that the more information put in the public domain, "the greater public confidence will be".

The family's barrister also urged Lord Hughes to consider ordering the government to identify Mr Skripal as a UK agent, despite its policy to "neither confirm nor deny".

Mr Skripal, who had been living under his own name in a quiet street in Salisbury, gave interviews to BBC correspondent, Mark Urban, discussing his links to MI6.

In 2017 he detailed his recruitment by MI6 in interviews with Mr Urban, for his book The Skripal Files.

Michael Mansfield KC, also acting on behalf of the family, told the inquiry at the Royal Courts of Justice in London, it was unlikely this account had been fabricated and the government should confirm whether Skripal was a spy.

Not to confirm or deny this was almost "Alice in Wonderland" he said.

"No-one is disputing he was a spy, at least for Russia."

Mr Skripal was convicted of high treason and espionage by Russia in August 2006 when it was claimed he was working for British intelligence.

"He was then involved in a spy swap", Mr Mansfield said. "A bit odd if he's not a double agent."

'Vital intelligence'

The chairman of the inquiry, Lord Hughes, said in response that establishing the facts of Mr Skripal's role was for the inquiry.

Cathryn McGahey KC, for the government, said that it would not abandon the principle of neither confirm nor deny (NCND).

She added: "Confirming a person is an agent may put that person at risk.

"Confirming someone is not an agent may put someone else at risk. That risk may be of death.

"Potential agents will not work for His Majesty's Government if they think their identities will be revealed in a public inquiry.

"If people will not work for us then vital intelligence will be lost."

Novichok was smeared on the door handle of Sergei and Yulia Skripal's home in Salisbury

She said it did not matter whether someone had claimed to be an agent.

A "hostile actor", she said, could plant stories, in the hope the government confirmed them.

The inquiry is considering an application from the government and police to prevent a large amount of information being put in the public domain, as part of the inquiry.

Lord Hughes said there were "great lists" of documents that would be considered individually, rather than preventing the publication of whole categories of information.

Both the families and the media have raised concerns about the application, warning that it risked breaching the principle of open justice.

Jude Bunting KC, representing the BBC and other media organisations, told the inquiry the government was trying to prevent information being published which "might" create a risk of harm to individuals or national security.

He said the test should be that it "would" create a risk.

Mr Bunting pointed out that some material had already been put into the public domain in the form of briefings by counter-terrorism police, chemical weapons experts and the Mark Urban book.

Following the open hearing on Wednesday, parties were set to discuss the disclosure of documents in further detail behind closed doors.

Substantive inquiry hearings are due to begin in Salisbury in October next year.

The first public open hearings will take place at the Guildhall in Wiltshire, from 14 October, before the inquiry relocates to the International Dispute Resolution Centre in London.

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, Twitter, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published24 March 2023

- Published25 March 2022

- Published15 July 2022

- Published28 December 2018

- Published13 September 2018