Discovering Malmesbury's 'gangster' medieval monk

- Published

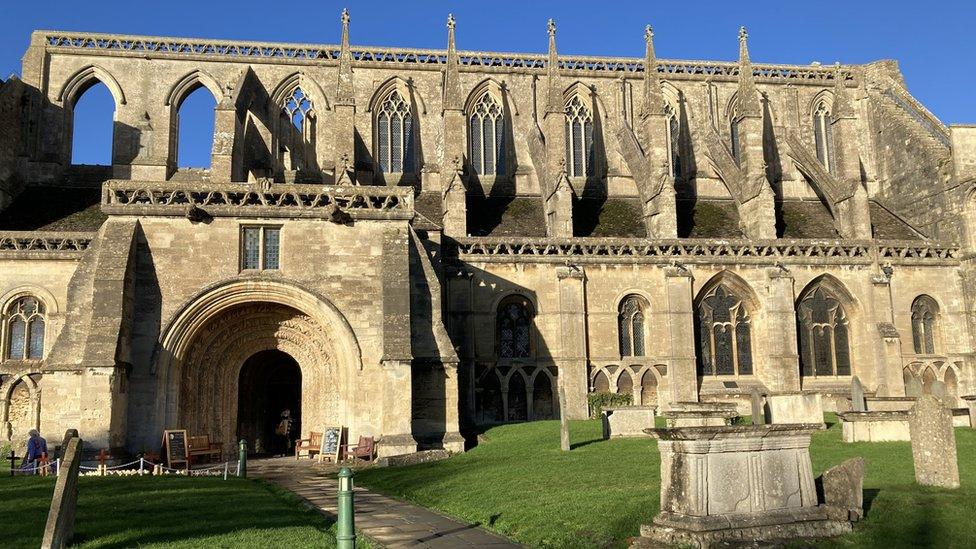

Malmesbury Abbey is still significantly the same structure it was when John of Tintern was a monk there in the 1300s

When a local historian started researching his town's abbey, he expected to uncover some surprises, but the evil nature of one character made him stand out above all others.

A wayward monk known as John of Tintern had such a colourful and criminal life that Tony McAleavy felt compelled to write a whole book chapter on him.

Idyllic Malmesbury is a market town in the Cotswolds, well-known for its Norman abbey, runaway pigs and being the burial place of Anglo-Saxon King Athelstan.

But it didn't always feel so serene.

While the monastery was dissolved in the huge religious changes ordered by King Henry VIII, it had been a centre of learning for centuries and an institution with power.

Speaking to BBC Radio Wiltshire, Mr McAleavy explained John of Tintern had a "very long criminal record," which first started in 1318.

He has combed through heaps of centuries-old documents in order to be able to tell his story.

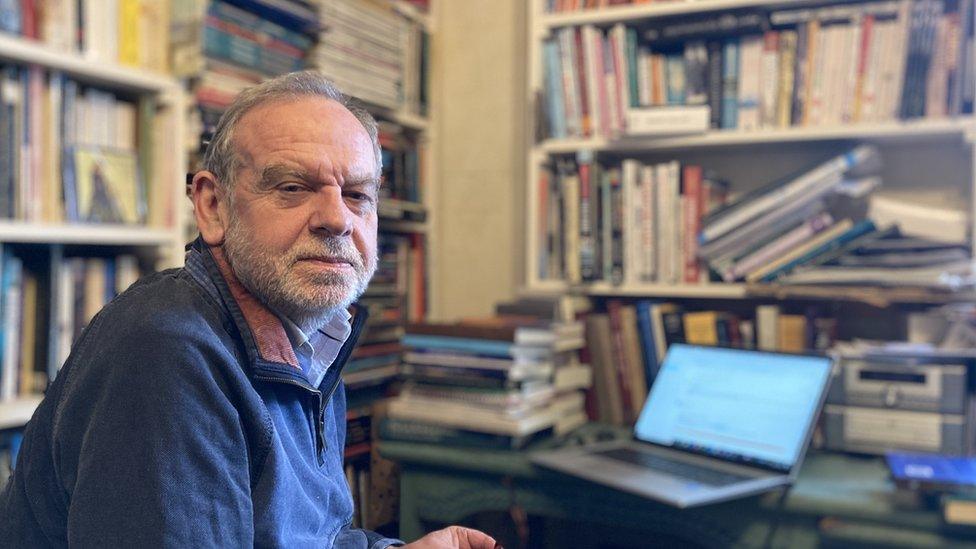

Tony McAleavy was researching for his book 'Malmesbury Abbey, 670-1539' when he discovered the criminal career of John of Tintern

'A mini army'

That year John, still a young monk, was put in front of the King Edward II and accused of being in a riot: "A mass brawl that took place in the town of Lechlade.

"He went there with 40 men from Malmesbury. A little mini army and they were engaged in some sort of argument about land and money."

The abbey was about to start a big building programme and needed cash: "this man is not someone spending all of his time with his prayer book. He is a man of business."

Malmesbury Abbey as it is today is partly a product of this moment in history - the top bit was rebuilt at this point, while the bottom was already in place.

The building there now is a small, but grand, a reminder of the whole abbey, as this section stayed as a church after the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1500s.

Malmesbury Abbey was having lots of building work done at the time - the top part of the building you can see was constructed in the time John of Tintern was there

Ruins of the rest of the grand monastery remain on the abbey grounds, which show the scale of the place

'Dark secret'

Then in the 1320s, the abbey became embroiled in a feud involving £10,000, which, by today's standards, would have been millions.

The monasteries at the time had political allegiances and at Malmesbury they supported a local noble family called the Despensers.

The family left a large amount of cash with the abbey for safekeeping.

However, when the tide turned against them, the head of the family was executed and the monastery decided to keep quiet about the money they had stored.

They even had a royal visit while they had the cash stashed there, likely in their living area, the only part of which remains in the basement of Abbey House in the town.

"The monks must have been terrified that they had this dark secret," Mr McAleavy said.

"They kept quiet about it, and then ten years later it came to light. Somebody obviously ratted on them."

As the right-hand man of the Abbot at the time, John was hauled in front of royalty once again and placed in custody.

In the end though, the monks of Malmesbury were pardoned: "Extraordinarily, the King took the 10,000 and let him off. Basically, they all got away with it."

This is part of the living area of the medieval abbey, now part of the basement of Abbey House next door

'Operated as a gangster'

Mr McAleavy explained that despite being elected as the Abbey's Abbot in 1340, John of Tintern was up to much worse.

"He operated as a gangster and a gangster who was prepared to kill or have his enemies killed."

To add to his unseemly behaviour as a monk, he was also living openly with a woman - Margaret of Lea, in a village next to Malmesbury.

He was accused of being the person to burn down the manor house her and her husband had been living in and abducting her.

It appeared to be a well-known story in the town, as local people came forward to report his crimes when the Justices travelled to Malmesbury from London.

John of Tintern became Abbot at Malmesbury, but did not behave much like one, even openly living with a woman

However, it was not only arson and abduction he was accused of - John of Tintern had ordered four murders.

Those killed were from the local gentry, some were tenants of abbey land and "it seems that John wanted to get rid of them, so that he could give the land, give tenancies to his cronies."

To make everything more corrupt, his ally was the Sheriff of Wiltshire himself, Gilbert of Berwick, who was supposed to be in charge of the county's law and order.

When the murders took place though, John was absent, getting a man from nearby Badminton to do the dirty work of beating and killing.

An arrest warrant was issued and they - Margaret included - went on the run.

Mr McAleavy explained that is not quite clear what happened, but they were found and put on trial in London.

It seems like this should have been the end of John of Tintern's escapades.

Mr McAleavy said a document in the Vatican archives shows that John of Tintern did have a guilty conscience later on

'They were pardoned'

"He literally got away with murder," Mr McAleavy said.

"The court accepted his guilt. They pardoned him in return for a massive fine so, basically he was fined for committing murder."

It was a fine of £500, the equivalent hundreds of thousands today.

Mr McAleavy believes that money played a big part in all of this, with the Abbey undergoing lots of building work at the time and hiring one of the top architects.

'A guilty conscience'

There is evidence in the Vatican archives that John of Tintern did feel some guilt though.

He applied to the Pope for something called an "indulgence".

Mr McAleavy explained this meant "approval from the Pope that at the moment of his death all his sins would be forgiven.

"That was just a standard transaction at the time in return for money.

"I think maybe he had something of a guilty conscience."

In 1349, John of Tintern died. It is not certain how, but the Black Death was ripping through the country.

It was a long research journey for Tony McAleavy who said: "You have to pinch yourself when you look at these documents.

"How can this possibly be true? How can this man of religion have behaved so incredibly badly?"

Follow BBC West on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk , external

Related topics

- Published8 December 2023

- Published20 November 2023