Remembering the York Minster fire 30 years on

- Published

It took four years and £2.25m to repair the damage caused by the fire at York Minster

York's divisional fire commander was fast asleep when the phone rang in the early hours of 9 July 1984. But within minutes, Alan Stow was fighting to save the city's most significant building from destruction.

Thirty years on, witnesses clearly remember the devastation caused by a lightning bolt which set fire to York Minster's south transept - destroying its roof and causing £2.25m worth of damage.

"My immediate thought was disbelief," Mr Stow said, remembering the 3am phone call. "Knowing the minster as I did and its security and fire defences, I thought, 'This can't be true'.

"Then I got onto Tadcaster Road and I could see the glow in the sky."

The previous night had been a "peculiar", airless evening during a hot, dry summer, said Mr Stow. The fire crew in York spent part of it watching lightning zip across the sky.

More than 100 firefighters tackled the blaze in the south transept of the church

Just a few hours later, at 02:35 BST, the control room at Northallerton received word the minster was ablaze. By the time Mr Stow arrived at 03:10, a third of the roof had been obliterated.

"The burning timbers were exposed and the fire was progressing rapidly," he said. "Bits of burning debris were leaping into the sky and the fire had almost spread through to the central tower."

It became clear the roof was beyond saving and bringing it down was necessary to save the rest of the building.

"[We positioned] a water jet onto the burnt timbers and they went down like a row of dominoes," said Mr Stow.

"They thundered down. I wouldn't have believed that a stone floor could shake but my word, it did."

Crews from across North Yorkshire were called to the scene, with 114 firefighters tackling the blaze.

Meanwhile, minster staff and clergy were removing as many artefacts as possible from the building.

John David, master mason at the minster, was one of those involved in the salvage operation.

"It was quite a traumatic night, it was surreal," he said.

"There was a fear the whole thing would go up, but we were busy getting the valuables out.

"The next day people were in tears and very upset, but as craftsmen, the first thing we thought was 'let's put it back, let's rebuild it'.

"There was no doubt we could do it. We wanted to put it back to the way it was."

An investigation concluded it was 80% possible the fire was started by a lightning bolt

By 05:24, the fire was under control, and as morning broke, the true scale of the devastation became clear.

An investigation into the cause of the fire ruled out an electrical or gas fault, while arson was discounted due to inaccessibility of the roof.

Some churchgoers feared the fire was a sign from God in response to the consecration at the minster three days earlier of the Bishop of Durham, David Jenkins.

He had made the news for saying he did not believe in the physical resurrection of Christ, external.

But subsequent tests concluded the fire was "almost certainly" caused by lightning striking a metal electrical box inside the roof.

However, with the evidence destroyed in the blaze, the official report could only conclude it was "80% possible" the fire was caused by lightning, and 10% each for arson and electrical fault.

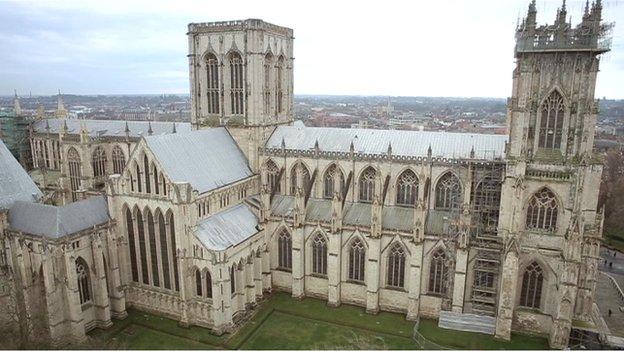

A restoration project to return the building to its former glory was finally completed in 1988, at a cost of £2.25m.

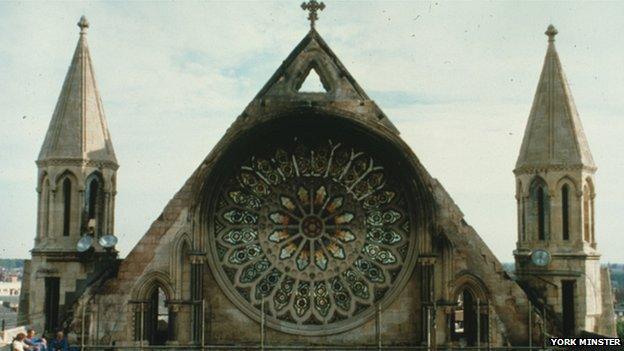

The rose window cracked in about 40,000 places but was saved by York Glaziers Trust

The site's masonry team spent a year re-carving bosses and stonework above the rose window and arches, while half a dozen bosses were designed by children in a competition run by Blue Peter.

It is thought the rose window, designed in the 16th Century to celebrate the marriage of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York in 1486, reached temperatures of 450C (842F) during the fire.

The glass cracked in about 40,000 places but was saved following painstaking work by York Glaziers Trust, external.

Bob Littlewood, former superintendent of works at the minster, was instrumental in replacing the vaulted ceiling and roof, which were gutted in the blaze.

The day after the fire he was offered 260 oak trees by people wanting to help rebuild the minster and tasked with convincing the church authorities to let him rebuild the roof with timber, in keeping with the original design.

Wood was agreed upon as the preferred material but on condition that parts of the new structure would be coated with fire-retardant plaster.

The restoration of York Minster was done in keeping with the original design

"Everything was gone," Mr Littlewood said. "We had to literally start from scratch.

"I didn't want anything modern and we all felt it should be done traditionally. Thankfully the Dean and Chapter agreed and I had the staff who were capable of doing the work."

Four years after the fire destroyed the south transept, the restoration was completed. It was a year ahead of schedule and thanks to the generosity of public donations, coupled with insurance money.

Mr Littlewood said: "Everyone buckled down and helped. It was a tremendous challenge, but I felt delighted at the end of the day.

"It was such a success and in fact, a big improvement on what was there before."

- Published16 March 2014