What is happening in Maghaberry prison?

- Published

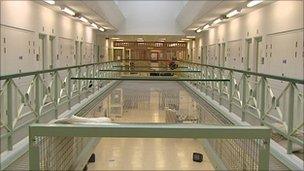

As mediators try to resolve an ongoing stand-off between dissident republican prisoners and the authorities at Maghaberry jail, BBC News Online looks at the background to the dispute.

As a movement which has always claimed to have liberty as its central goal, it is perhaps unsurprising that Irish republicanism has a long and tortuous relationship with prisons.

Practically every incarnation of the movement has had its own narrative about how its struggle continued from behind bars and walls.

The most recent example is the hunger strike of 1981 when ten prisoners starved themselves to death in protest at their failure to secure concessions from the British government.

Nor have the mists of time obscured republican memories of how an IRA leader was spirited to freedom when a helicopter landed in the grounds of a Dublin prison in 1974.

Going further back, the candidacy of an imprisoned Easter Rising leader in the general election of 1918 was marked by posters urging voters to "put him in, to get him out".

Barricaded

Thus the pattern of history appears to dictate that the renewed violence of another generation of Irish republicans should be accompanied by the prominence of its prisoners.

Last weekend, about 100 supporters of current republican prisoners marched in protest from west Belfast to the centre of the city.

They walked to highlight an ongoing dispute between republican prisoners and the authorities at Maghaberry.

While it is a truism to say that relations between the two were never warm, the current row came to a head on Easter Sunday this year.

Twenty-eight prisoners on the specially designated republican wing barricaded themselves into the prison canteen and smashed toilets in their cells.

Prisoners have been pouring their own urine out on to the landing

Since then, they have spent 23 hours a day locked in their cells.

The riot on Easter Sunday had both specific catalysts and wider causes.

In the short-term, prisoners claim that they that they are being made to undergo more full-body strip searches than those who are euphemistically called "ordinary, decent criminals".

They have also complained about a regime of "controlled movement" which means the number of prisoners allowed out of their cells is determined by the number of prison officers available to supervise them.

Excrement

On the other hand, the chants of the marchers last weekend demanding "political status now" reflect a wider goal.

It is a similar demand to that of republicans in the 1970s.

To achieve their goal, they began a "dirty protest" - involving smearing their own excrement on the cell walls - which eventually evolved into the hunger strike of 1981.

The British government refused to grant political status, with Mrs Thatcher famously stating that "crime is crime is crime".

However over the next two decades, the prison regime evolved to the extent that paramilitary prisoners did effectively have special status - for example, running their own blocks with minimal interference from the authorities and wearing their own clothes.

So, while the government reiterates that it will not give dissident republicans political status, these prisoners have a historical template to cling to.

They are using similar methods to attain a similar goal.

The Prison Service has had to issue staff with special protective clothing after prisoners began pouring urine, sometimes mixed with excrement, onto the landings.

Some prison officers have had discarded urine aimed at them through gaps in the door.

And one prisoner, Liam Hannaway, a cousin of Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams, went on hunger strike for 42 days in protest at not being allowed to serve his sentence alongside other republicans.

Westminster

Whether today's prisoners will make any progress towards their wider aim of political status has to be answered in the light of a very different context from 1981.

Then one of the hunger strikers, Bobby Sands, was elected to Westminster while on his fast.

His success is seen as having been the trigger for Gerry Adams own election to the House of Commons in 1983 and the subsequent meteoric rise of Sinn Fein to being the second biggest party in the NI Assembly.

The republicans who are imprisoned in Maghaberry and their supporters outside seem to have little interest in creating a similar electoral thrust.

Bobby Sands was elected to Westminster during the 1981 hunger strike

In any case, republicans who have stood against Sinn Fein candidates in elections since the Good Friday Agreement have been hammered at the polls.

The republican electorate seems content with Sinn Fein's analysis of the way forward.

Nevertheless, Gerry Adams and his colleagues are being careful not to dismiss the prisoners' demands.

Sinn Fein representatives have been to visit Maghaberry since the protest started and on Monday, Mr Adams called on the authorities to respect the rights of the prisoners.

Establishment

Mainstream republicans know better than anyone the potential power of a prison protest.

Their efforts have not been warmly welcomed with the prisoners accusing Sinn Fein of being part of the establishment they blame for the conditions inside the prison.

The potential difficulties are not lost on the authorities either who have called in mediators to try to resolve the dispute.

Three weeks of talks ended last Friday night, with the prisoners and the prison service each blaming the other.

However, the mediators are engaging in meetings with the prison service in an effort to resurrect the process.

The history of such disputes dictates that it is not a problem the authorities can afford to ignore.

- Published9 August 2010

- Published30 July 2010