NI internment remembered 40 years on

- Published

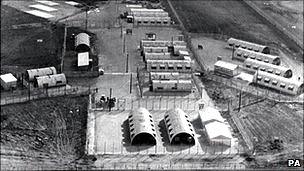

Those arrested under internment were imprisoned in the Maze

"I was on my way home after being at a party. A number of soldiers came out of my mother's house, surrounded me and put me in the back of an army jeep."

Jim Auld's arrest, at half past three on the morning of 9 August 1971, marked the beginning of Operation Demetrius.

By the end of the day 342 people were detained.

The government had decided that imprisoning people without trial was the only way they could restore order to Northern Ireland.

In an interview with the BBC's John Humphrys, the Unionist Prime Minister Brian Faulkner said: "The gunmen have been brought out into direct confrontation with the security authorities. If there are gunmen around, that is the only way to deal with them."

But instead of stopping the violence, internment only inflamed it.

Twenty five people died in street violence in the four days after the policy was introduced.

Whole districts were left in ruins by rioters - 7,000 people left their homes.

One of the first problems with the policy to become clear was that a significant number of internees were not in paramilitary groups.

Paddy Joe McClean, a civil rights activist from County Tyrone, was interned despite having spoken out against violence.

He had criticised the army and police as well.

"I am inclined to the view that when internment was brought in, the government forces decided that all protesters should be picked up," he said.

He and 13 others became known as the "Hooded Men" after two priests - Fr Raymond Murray and Fr Denis Faul - recorded their accounts of being interned.

It included allegations of ill-treatment.

Former IRA member Francis McGuigan recalled: "I was physically dragged and placed against a wall in the stretch position: fingertips to the wall, feet well apart. Then the white noise started."

The Irish government took a lawsuit based on the accounts to the European Commission on Human Rights in 1976.

The commission ruled that the security forces' use of five techniques - white noise, sleep deprivation, wall-standing, beatings and the deprivation of food and drink - amounted to torture.

A later case, before the European Court of Human Rights, concluded that the techniques were inhumane - but not torture.

Internment lasted until 1975.

The introduction of internment led to a lot of unrest on the streets of Belfast

More than 1,900 people were interned, of which approximately 100 were loyalists.

Sammy, a loyalist, said the policy "divided Belfast".

Recalling his two years as an internee, he said: "It had a huge impact on my family. I was the chief breadwinner. After I was released, I found it very difficult to re-adjust. People were reluctant to employ me."

At the time, internment may not have seemed such a bad option for the government.

Sir Kenneth Bloomfield, who was a Stormont civil servant at the time, said on previous occasions, internment had succeeded.

"But it soon became clear that far from quelling the uprising, the policy hugely increased recruitment into the IRA," he said.

With 40 years' hindsight, the historical consensus is that internment did the opposite of what it was supposed to do.

Patrick Mercer, a Conservative MP who served in the army in Northern Ireland, said: "It stoked the conflict for at least the next 10 years, if not 20."

Watch BBC Newsline on Tuesday 9 August for more on the 40th anniversary of internment.