Gaddafi death, the Eta ceasefire and Northern Ireland

- Published

- comments

Gerry Adams tried to consign the Colonel Gaddafi link to the past and associate republicans with the Arab Spring

Two major international stories were featured on the BBC 10 o'clock news on Thursday night, both with a direct connection to Northern Ireland.

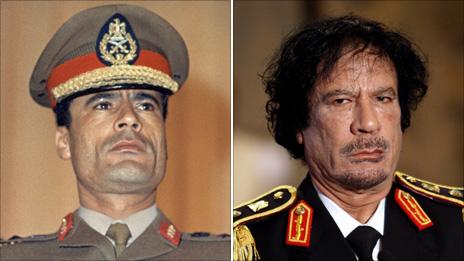

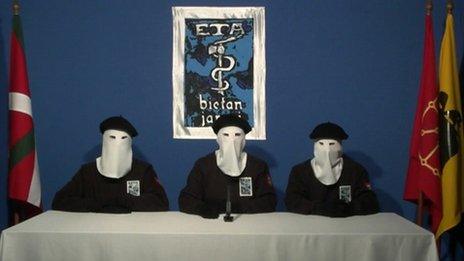

The grisly death of Muammar Gaddafi inevitably dominated, but the bulletin also found space for the Basque separatist Eta's "definitive cessation of violence".

James Robbins' report on the Eta ceasefire included positive soundbites from Tony Blair and Gerry Adams.

It crossed my mind that both politicians would find it more comfortable to comment on the developments in the Basque city of San Sebastian, than the horror in the Libyan town of Sirte.

The former Labour prime minister defends his attempt at detente with the Libyan colonel as a pragmatic gesture, necessary to rid the world of weapons of mass destruction.

Nevertheless, his infamous handshake in the desert with a man deemed to be behind both the Lockerbie bombing and the IRA's Semtex attacks isn't likely to be the image by which Mr Blair would want to be remembered.

Basque separatists Eta announced on Thursday they were ceasing violence

For the Sinn Fein president, recounting the role of Father Alec Reid and other Northern Ireland figures in fostering peace in the Basque country is an easier chapter to recall than the IRA's long-standing relationship with the Gaddafi regime.

On Good Morning Ulster on Friday, Mr Adams faced questions about both areas.

He acknowledged the Colonel as a "friend of the IRA", but wouldn't be drawn on whether this relationship is now a "grubby" embarrassment.

Instead Mr Adams tried to consign the Gaddafi link to the past and associate republicans with the Arab spring, drawing parallels between the uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East and the struggle for civil rights in the 1960s (this mirrored comments made to me by Martin McGuinness back in the early days of the Libyan rebellion).

Mr Adams indicated that no-one should revel in the ghastly death of the Colonel.

With video showing Gaddafi alive when he was captured, there are widespread suspicions that the dictator was executed, rather than shot in crossfire.

Certainly the manner of his passing, whilst predictable, is disturbing for all those who believe in the rule of law.

Analogy

On BBC Radio Ulster's Nolan programme, some callers, having watched the images of the semi-naked Colonel, recalled their memories of the mob murder of the two British corporals who were beaten, stripped and executed after they drove into an IRA funeral in west Belfast in the 1980s. Other callers rejected the analogy.

Unionists, like Jeffrey Donaldson and Nigel Dodds, and the relatives of IRA victims, like Colin Parry and Willie Frazer, are hopeful that the change of regime in Tripoli will not derail their attempts to secure compensation for the families of those killed and injured by Libyan-supplied Semtex.

The new Libyan leadership will no doubt have other pressing priorities, but the key role played by the UK in Colonel Gaddafi's overthrow could potentially bolster the IRA victims' case.

The Eta ceasefire could also have some significance back in Northern Ireland, if it proves to be the most tangible example yet of the possibility of exporting peace.

Lessons

Next month, the European Union is due to make a decision on funding a Conflict Transformation Centre at the site of the former Maze jail.

The first and deputy first ministers were already confident of securing European support, but if the Basque process is consolidated it can do nothing but help their argument.

There's already a "cottage industry" involving people from conflict zones around the world travelling to Belfast to examine if there are any lessons they can usefully apply to their own regions.

Just this week, for example, a delegation visited Stormont from the disputed territory of Nagaland in the north-east of India.

Presumably if an EU-recognised centre is developed at the Maze, it will encourage such visits.

Of course there's a quite separate debate about what, if any, lessons other regions can draw from our experience.

Was it all about talking and common sense conquering all? Or should more inconvenient truths be acknowledged?

Last year, Robin Wilson produced a book pointing out the limitations of exporting the Northern Ireland settlement as a model for others, external.

Recently in the Guardian, external, Henry McDonald drew attention to the unspoken role of security force infiltration inside the IRA.

Feisty exchanges

Just last week I attended a seminar at Birkbeck College in London during which there were some feisty exchanges between academics.

Martyn Frampton and John Bew's book, Talking to Terrorists?, deals with analogies with the Basque country and also emphasised the importance of the British "Dirty War".

Kingston University's Paul Dixon disagreed, arguing this amounts to a "neo-conservative" re-writing of history which emphasises the "military defeat" of the Provisional IRA at the expense of the various players' commitment to dialogue and political progress.

If and when Europe approves a peace centre at the Maze, thoughts will have to turn to which ideas might be propagated inside the building; not only in relation to what happened at the jail, but also regarding Northern Ireland's place in the wider world.

Rather than trying to develop a prescribed version of history, it might be better - to borrow a phrase from Chairman Mao - to let "a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend".

That way different politicians, academics and other participants could say what they want about Colonel Gadaffi and the Provisional IRA, the Hunger Strikes and the "Dirty War", the Stormont settlement and "exporting peace".

Foreign visitors could then make their own minds up which lessons, if any, might prove valuable for their own conflict zones.

- Published21 October 2011

- Published20 October 2011

- Published21 October 2011

- Published20 October 2011