Irish presidency: candidates go from sinner to saint

- Published

The Irish presidency is largely a symbolic role but election campaigns have proven far more controversial than parliamentary ones where real power is at stake.

The campaign to succeed President Mary McAleese is now nearing a conclusion. And true to form, in the eyes of many it is proving a lot more vitriolic than this year's general election.

In general elections there are policies to analyse and pore over but in a presidential contest there is really only a candidate's past.

Apart from the "soft authority" a directly elected president can exercise, there are constitutional restrictions on what he or she can say and do.

Revelations

Sinn Fein knew that Martin McGuinness would be questioned about his IRA past.

David Norris' withdrew from the campaign after controversy but later rejoined

He knew there would be considerable media and political scepticism about his claim that he left the IRA in 1974 but many assumed the issue would pass as he focused more on peace process work.

That has not happened.

The campaign of independent candidate, Senator David Norris, never recovered from revelations that he had written to the Israeli authorities and others seeking clemency for his former partner, who was found guilty of the statutory rape of an underage Palestinian boy.

The one-time favourite's decision not to publish those letters - he says on legal advice - further undermined his faltering challenge.

Dana Rosemary Scallon's campaign has been dogged from the moment of her last-minute entry.

The former Eurovision Song Contest winner has seen the details of a bitter family dispute over her American business interests pored over in the media.

She says the claims made against a family member are "vile, malicious and untruthful."

Indeed, at one stage, it was suggested that the tyres of her car had been deliberately knifed and there was a "plot" to kill her.

The other candidates have also faced the media glare.

Sean Gallagher, the favourite according to one poll, has had to answer questions about his Fianna Fail past - the party is still seen as toxic because of its role in last year's EU/IMF bailout.

One of the dragons in the Irish version of Dragons' Den he has also been forced into admitting to "an honest mistake" that was "quickly corrected" in his tax affairs.

Mary Davis, another independent candidate, has had to deny that she is a "quango queen". The woman who oversaw the Special Olympics in Ireland in 2003 also faced criticism that she's bland.

Labour's Michael D Higgins has battled against claims that he is too old and Fine Gael's Gay Mitchell has faced questions about his unpopularity - even within his own party.

His popularity rating is way behind his party's.

But intense media scrutiny is nothing new to presidential campaigns.

'Bridge-building'

More so than in general elections, it is as if the election to become Ireland's first citizen allows the people and commentators a chance to audit the country, its values and where it wants to go.

Mary McAleese enjoys huge popularity ratings but also faced criticism over her candidature

And that means the record of every candidate is closely examined.

The presidency in recent times can be seen as foretelling the direction the republic is moving towards.

That may help to explain why Mary Robinson's election in 1990 heralded a more liberal and less Catholic country while seven years later Mary McAleese's "bridge-building" theme foreshadowed what politicians south of the border believe was the reconciliation of the Good Friday Agreement a year later.

But Mrs McAleese's campaign was not without controversy. When she stood 14 years ago one commentator described the candidate originally from north Belfast as "a tribal time-bomb" - he has since changed his view.

This followed the leaking of internal Department of Foreign Affairs memos that seemed to hint that she was sympathetic to some Sinn Fein arguments.

The 1990 campaign that heralded the modern presidency was, if anything more colourful and more controversial, than the 1997 one.

The Fianna Fail candidate, Brian Lenihan, was sacked as deputy prime minister by his old friend Charles Haughey at the insistence of his coalition partners, the Progressive Democrats, in a row over whether phone calls had been made to President Hillery asking him not to dissolve the Dail in 1982.

Mr Lenihan, who had had a liver transplant and was on heavy medication, told a post-graduate student that he had made the calls but then in an RTE interview, looking straight down the lens of a camera, told the Irish people that "on mature recollection" he had been mistaken.

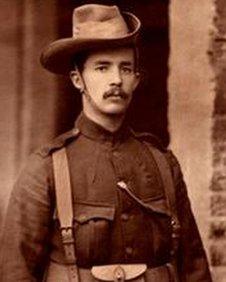

Erskine Childers told his son to shake the hand of those who had signed his death warrant

Other past contests have seen General Sean Mac Eoin stand for Fine Gael. An old IRA veteran, he had no problem admitting to his involvement in actions that led to the killings of RIC policemen.

Fianna Fail's Eamon De Valera, whose 1937 constitution created the presidency, took part in the 1916 Easter Rising against the British but as prime minister he was also responsible for the execution of IRA members who endangered the new Irish state.

Poignant

Perhaps the most poignant campaign was in 1973 when Fianna Fail's Erskine Childers defeated Fine Gael's Tom O'Higgins.

President Childers father, who was also called Erskine, was a British soldier and writer who became an ardent Irish republican.

Like De Valera he opposed the treaty that set up the Irish Free State and was executed by the new Irish authorities for the possession of a pistol, ironically, a present from Michael Collins.

Before his death, Erskine Snr got a promise from his then 16 year old son to seek out and shake the hand of all those who had signed his death warrant. He duly did.

Tom O'Higgins' Uncle Kevin was a justice minister in the new Irish state that was finding its feet after a bitter civil war over the treaty.

The new government took an uncompromising view on continuing republican activity.

But in 1927 the IRA murdered Kevin O'Higgins on his way to Mass.

Both presidential candidates stood on their records but the electorate was keenly aware of their family histories.

Mary Robinson was seen as having created a new era for the presidency

Because Irish presidents, like the British Queen, are above politics and not meant to comment on topical political issues, they are almost treated with reverence once they are elected.

All of which makes the close and detailed examination of a candidate's record, according to some, or the vitriol and nastiness of the campaign, according to others, seem curiously at odds with the office itself.

And despite the twists and turns whoever succeeds President McAleese can almost certainly be guaranteed - barring unforeseen circumstances - positive media coverage and high popularity ratings.

It is a bit like going from sinner to saint in the course of a few weeks campaigning.

- Published28 September 2011

- Published22 October 2011

- Published19 September 2011