Titanic's unsinkable stoker

- Published

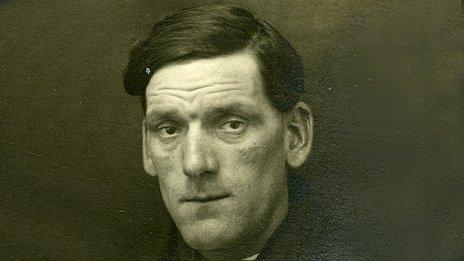

John Priest

Titanic was celebrated as the biggest, safest, most advanced ship of its age, but it was a lowly stoker in its boiler room who truly deserved the name 'unsinkable'. John Priest survived no fewer than four ships that went to the bottom, including Titanic and its sister ship Britannic.

John Priest was one of more than 150 'firemen', or stokers, whose job it was to keep Titanic's 29 colossal boilers at steam, day and night, for the entire journey.

He had worked his entire life as a member of the so-called 'black gang', toiling in the bowels of steam-powered ships. It was back-breaking work, often done stripped to the waist due to the ferocious heat of the furnaces.

Titanic being tugged out to Sea from Belfast

Even in a state-of-the-art vessel like Titanic, the work was still done by muscle power alone. More than 600 tonnes of coal a day were needed to propel what was then the world's biggest ship through the ocean. 'Trimmers' wheelbarrowed coal from the bunkers to the firemen who maintained the furnaces. Both were relatively skilled jobs, with the trimmers having to ensure the weight of the coal was evenly distributed so the ship stayed balanced, or 'trimmed', while the firemen needed to feed just the right amount of coal into the flames to keep the ship at the required speed.

With the coal strike of 1912, the black gangs were hit hard as ships stayed in port and men were laid off. Priest was one of the lucky few to find a job on Titanic as it prepared for its maiden voyage across the Atlantic. He was perhaps fortunate to have already served on Titanic's sister ship Olympic and was a fireman on board when it was holed below the waterline in a collision with the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Hawke in 1911.

The Olympic crash wasn't Priest's first brush with disaster. He had previously worked aboard a ship called the Asturias that was badly damaged in a collision on its maiden voyage. But this was an age when accidents, near-misses and sinkings were relatively common.

Even so, the remainder of his career at sea was to be a remarkable tale of survival against the odds. He would claim in later life that men refused to sail with him because he brought bad luck. It's hard not to see their point.

From steaming furnace to freezing water

When Titanic hit an iceberg just before midnight on Sunday 14 April 1912, many of the passengers and crew were unaware that anything was amiss until the engines stopped. In the very bowels of the ship, Priest was off duty and resting between shifts.

The odds against his survival were steep, due to his both his physical and social position within the ship. The route to the deck took him and other members of the black gang up through a maze of gangways and corridors before they could reach the deck. By the time they emerged into the freezing night air, most of the lifeboats had already gone.

Those firemen who survived - 44 in all - swam for their lives through water just marginally warmer than freezing, wearing only the shorts and vests they worked in. Small wonder that Priest suffered frostbite.

Another survivor, a lookout by the name of Archie Jewell, wrote to his sister describing the moment Titanic sank.

"I shall never forget the sight of that lovely big ship going down and the awful cry of the people in the water and you could hear them dying out one by one; it was enough to make anyone jump over board and out of the way. I can't help crying when I think about it."

The 'Great War'

When World War I broke out in 1914, merchant vessels, and their crews, were required for the war effort to serve in convoys and as hospital ships. By 1915, Germany had unleashed its U-boat fleet in a bid to choke off Britain's supply lines. The toll on the merchant fleet was horrendous.

Priest was among those who went to war, serving aboard the armed merchant vessel Alcantara. In February 1916, Alcantara intercepted the German raider Grief, which was disguised a Norwegian ship. As Alcantara approached, Grief opened fire. There was a short, ferocious, close-range battle, at the end of which both ships were sunk.

More than 70 of Priest's shipmates were killed and he only narrowly escaped, with shrapnel wounds.

When he returned to work, it was aboard Britannic, Titanic's other - even bigger - sister, which was serving as a hospital ship ferrying wounded soldiers back to Britain through the Mediterranean. Having already survived a collision on Olympic and the loss of Titanic, it must have been with no small amount of trepidation that he joined the third of the celebrated White Star Liners.

Joining Priest on board were two other Titanic survivors; Archie Jewell, the lookout, and Violet Jessop, a White Star stewardess who was now serving as a nurse.

If Priest did feel any nervousness, it was entirely justified. On 21 November 1916, the great ship struck a mine and sank near the Greek island of Kea. Once again, he emerged from the very depths of a foundering ship alive.

Indeed, the majority of the ship's crew were evacuated safely, but two of the lifeboats were lowered into the sea too early and were sucked into the ship's still turning propellers, killing 30 men. Among those pulled into the blades was Archie, who somehow survived.

In a letter to his sisters he described his escape:

"... most of us jumped in the water but it was no good we was pulled right in under the blades...I shut my eyes and said good bye to this world, but I was struck with a big piece of the boat and got pushed right under the blades and I was goin around like a top...I came up under some of the wreckage ... everything was goin black to me when some one on top was strugling and pushed the wreckage away so I came up just in time I was nearly done for ... there was one poor fellow drowning and he caught hold of me but I had to shake him off so the poor fellow went under."

Violet was also in danger of being pulled into the propellers, but dived clear and was sucked underneath, striking her head on the keel. She was rescued by another lifeboat.

After Britannic, Priest would achieve one final escape from a sinking ship. On 17 April 1917, he was a fireman aboard the hospital ship Donegal when it was torpedoed and sunk in the English Channel. He suffered a head injury and would not serve again during World War One. Fellow Titanic and Britannic survivor Jewell was among the 40 men who went down with the ship.

'Unsinkable'

Priest's is an amazing story of human endurance. He worked his entire life in extraordinary conditions in the belly of the ship, where fires and explosions were common. He was often at the very worst part of a vessel from which to escape and yet he survived an astonishing litany of torpedoes, mines, icebergs and collisions to live out his days spinning tales in the pubs of Southampton.

He died in 1937, on dry land. Truly, the name "unsinkable" applied rather better to him than it did to the mighty Titanic.

- Published31 March 2012

- Published15 April 2013