Titanic Village: The sinking of dreams

- Published

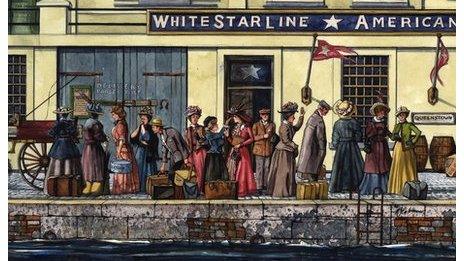

Queenstown Port 1912 - the last point of the Titanic's journey.

When Titanic sank, eleven people from a single village in Ireland lost their lives. It was the highest proportional death toll of any place in the British Isles and had a devastating emotional and economic impact that reverberates to this day.

In the early 20th century, emigration from poverty stricken west of Ireland had a well-established pattern. The chain of migration was built on a delicate cycle of loans and remittances, with money constantly being sent home to fund the next wave. Ships like Titanic were literally selling tickets to a new life.

In all, 14 men and women from Addergoole, a small village in County Mayo, Ireland, boarded the new White Star liner Titanic on 11 April 1912. Theirs is the human story of emigration and the cost of the tragic sinking for one community. The impact was so huge, that its resonance is still felt a hundred years later.

The business of emigration

The demand at this time for safe and fast Atlantic passage was huge. By 1910, more than 13,000,000 immigrants were living in the USA, the majority of them from Europe. This demand was a key driver in White Star Line's decision to build the 'Olympic class' liners Olympic, Titanic and Britannic.

By 1912, emigration from the west of Ireland was still rising steadily and $10 million a year (more than £400 million in today's money) was being sent back to Ireland from those who made it to America. Emigration was a profitable industry.

A network of local businesses sprang up to deal with the demand. Ticket agents went door to door, shops of every kind sold tickets and even schoolteachers supplemented their income selling passage on the White Star Line.

The fourteen emigrants from Addergoole met the Titanic at Queenstown (now called Cobh), its last stop before New York. More than 30,000 people passed through the bustling port every year and lodgings were rented out for nearly a week's wages for a single night. Like thousands of others, the Addergoole party would have paid up, knowing they stood to make their money back many times over when they reached America.

Most were going to join relatives who had already emigrated. They ranged in age from 17 year old Annie McGowan, travelling with her aunt Catherine, to 42-year-old John Bourke, accompanied by his new wife, also called Catherine.

Little is known about how the fourteen spent their last night ashore before boarding Titanic, but the story of what happened next has been told and retold for a century. Initial reports filtering back to Ireland said the ship was damaged but in no immediate danger. This couldn't have been further from the truth.

A terrible grief

The shipping agent who had sold most of the tickets to the Addergoole party was Thomas Durcan. It was he who contacted White Star Line and confirmed the terrible news to the community.

The village was stricken with absolute grief. It took weeks for families to find out whether their loved ones had survived. For a close knit community like Addergoole, nearly everyone was linked by ties of family or friendship.

A local newspaper, the Western People, described the scene:

"…when the first news of the appalling catastrophe reached their friends the whole community was plunged into unutterable grief. They cherished for a time a remote hope that they were saved. But when the dreaded news arrived a feeling of excruciating anguish took its place."

When the Titanic sank, the delicate chain of emigration was broken. Addergoole had pinned its hopes on the 14 men and women who had departed Titanic. They were family and friends, but they were also an investment.

Families had little hope of paying back loans or funding another member to emigrate with no money coming back from America.

There was little help for them in their distress. The shipping agents, Thomas Durcan and Mrs Walsh, went to extraordinary lengths to help the victims' families, lobbying the White Star Line, the Lord Mayor of London, the Countess of Aberdeen and the Board of Trade. It is not known if they were successful.

What is certain is that the families were plunged into terrible financial hardship and their grief left them unable to talk about loss, such that later generations would grow up in the village with no knowledge of the Titanic catastrophe.

Dr Paul Nolan, chairman of the Addergoole Titanic Society explained:

"At the time, the first descendants didn't talk about it, the second didn't know about it, and by the time it came to the third it was basically forgotten … it was done for certain reasons, perhaps embarrassment, perhaps failure, and serious disappointment … but we're not ashamed of these things, it was an emotional story."

If Addergoole's Titanic tragedy had one positive outcome, it was for the three survivors who were rescued and taken to America.

The Addergoole fourteen, waiting to board Titanic. Depicted by Micheal Coleman

Annie McGowan, the youngest member of the party, made it into a lifeboat and was taken aboard the Carpathia at 5am. Her aunt, Catherine, perished. Annie's eyes were bleeding from the salt water and exposure and it took her months to recover.

She was eventually discharged from St Vincent's Hospital in New York with only a nightgown and a coat to her name. The Chicago Tribune newspaper told the story of Annie and another Addergoole survivor, Annie Kate Kelly, aged 20:

"They were given an old pair of shoes, but they were forced to make the trip from New York to Chicago in their coats and night gowns. They had no dresses nor underwear. Anna (sic) McGowan is the oldest girl of seven children. The remainder of her family are in destitution in Ireland."

Annie Kate Kelly had written to her cousin in Chicago before boarding Titanic:

"I am coming to America on the nicest ship in the world. I am coming with some of the nicest people in the world, too. Isn't that just splendid? They live in Chicago, and I shall be able to make the entire trip with them. They have told me all about Chicago and I know that I shall like it much better than I do Ireland."

Annie Kate only survived because another passenger refused to get into the lifeboat:

"As the ship was sinking, women and children were evacuated first. They formed a line. A young bride refused to leave the ship without her husband. I was given the bride's place. As I was lowered into the lifeboat I looked up and saw my cousin Pat watching, holding in his hand his rosary, which he raised to bless me."

Her cousin, Pat Canavan, drowned. His body was never recovered.

The final survivor, Delia McDermott, aged 31, was saved despite going back to her cabin to retrieve her hat. She jumped 15 feet into one of the last lifeboats to leave.

All three women stayed in America for the rest of their lives. Annie McGowan and Delia McDermott both married, while Annie Kate Kelly became a nun.

Addergoole now commemorates the tragedy every year in a bell ringing ceremony. In the centenary year, they will also re-enact the route that the 14 would have taken to the railway station to depart for the first leg of their journey. The village is finally coming to terms with its place as the 'Titanic Village'.

- Published30 March 2012