Good Friday referendum: Nationalists and Alliance reflect

- Published

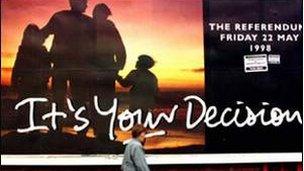

Exactly 15 years ago - May 22 1998 - voters went to the polls to vote yes or no for the Good Friday Agreement. In the second of a two-part series, the BBC assesses the challenges nationalists and others still face.

The final result: 15 years ago

The vote for the Good Friday Agreement was predicted to be close on the unionist side, but not so for nationalists.

In overwhelming numbers, on both sides of the border, nationalists marked Yes on ballot papers.

Although the turnout in the Republic of Ireland was lower than in Northern Ireland, the endorsement was 94%.

For SDLP negotiator, Alex Attwood, it was a moment of hope.

Fifteen years on, he is the party's sole minister in an executive dominated by Sinn Fein and the DUP. He suggests hope has given way to haughtiness and hostility.

"There is an arrogance. There is an elitism around the executive table and in politics where those who are the biggest, think they know best. Well, I think the last six months have demonstrated they don't know best," he said.

Mr Attwood pointed to the flags protest which led to street violence and said the two governments and all the parties were needed to tackle unfinished business.

He said these included issues of the past as well as challenges such as a review of north-south relations.

"There is, in the Scottish programme for government, a chapter on political humility. I think there are some around the executive table who need to read it," he said.

It is the kind of criticism the DUP and Sinn Fein brush aside as sour grapes from those who have lost ground since 1998.

The Alliance Party leader David Ford, one of the negotiators of the Good Friday Agreement, is now justice minister in the executive and has his own concerns.

He is unimpressed with the way the Shared Future policy has been handled by the first and deputy first ministers of late. And he questioned whether the current "rigid" structures are delivering the kind of partnership government required.

"We certainly need to ensure we look at what is best for the future and don't assume that what was agreed on Good Friday 1998 must last forever," he said.

Mr Ford expressed disappointment with those who continually "hark back to the past".

Another perspective

"They may talk about building a united community but when some people spend their time pandering only to the needs of one section of the community, it doesn't look that they've brought that new vision which I believe is absolutely essential."

The perspective is a little different from the deputy first minister's office.

Martin McGuinness said both he and the first minister jointly began round-table talks this week with the five executive parties to deal with the outstanding issues. He said he and Peter Robinson were doing their best to deal with problems following years of conflict.

"It's our duty and responsibility as leaders to work together to try and forge agreements, to try and forge economic prospects for the people that we represent whilst, at the same time, recognising that every now and again there will be situations that jump up to bite us," he said.

"What we have to try and do is minimise those situations."

He said the flags dispute was one of those situations.

Unlike his partner in government, Peter Robinson, who voted no, Mr McGuinness led the yes vote in 1998. It was not a partnership he anticipated 15 years ago, but he insisted they have a good working relationship despite tensions.

He said they were at their strongest when standing against the violence of dissident republicans who just last week tried to kill police officers in west Belfast.

He said dissident republicans needed to understand that the logic of the Good Friday Agreement was support for the police. He said this is what turned some republicans off the peace process.

Voters went to the polls on 22 May 1998

"What they need to understand is that I cannot be a minister in government dealing with all sorts of major issues that affect people's lives and then, when a journalist comes up and asks me about an attack on a policeman, that I am going to stand and justify that. I cannot justify that," he said.

"I am either fully 100% a government minister pledged to a peaceful way forward or not.

"And I think that is what some of these people expected. They actually expected that you can be in government, take all of these decisions whilst at the same time people outside of that arena would have the right to attack and kill police officers. You can't do that."

Mr McGuinness said this minority had no support and no right to use violence. Republicans who did vote no in 1998 did so in part because they believed the deal would strengthen, not weaken the union.

I put it to Mr McGuinness that opinion polls suggest growing support for the union.

He responded: "Many people said to me in the past that they believed many unionists worked on that basis that if nationalists or Catholics got equality then that was the end of the union as they know it. We're in a different place. I'm here on the basis of equality.

"What we have to do as we move forward - and I move forward as an Irish republican who is working to bring about the unity of the people of Ireland and a united Ireland - is that I am pledged to do that by purely peaceful and democratic means."

- Published22 May 2013

- Published23 May 2013