On the Runs - key questions and inquiry findings

- Published

IRA prisoners on early release emerge through the Maze Prison turnstile in 2000

Who are the on the runs?

The Northern Ireland Good Friday Agreement of 1998 meant anyone convicted of paramilitary crimes was eligible for early release. However, this did not cover those suspected of such crimes, nor did it cover people who had been charged or convicted but who had escaped from prison.

Negotiations continued after the signing of the agreement between Sinn Féin and the government over how to deal with those known as On the Runs.

Sinn Féin sought a scheme that would allow escaped prisoners and those who were concerned they might be arrested to return to the UK, but a formal legal solution proved difficult to establish in the face of strong unionist opposition.

Against this backdrop, the IRA had still not put its weapons beyond use and Sinn Féin needed grassroots republicans to continue supporting the peace process.

What are the On the Runs letters?

Gerry Adams received a letter from Tony Blair

In May 2000, Prime Minister Tony Blair told Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams that if he provided details of those on the run, these would be examined by the attorney general in consultation with the police and the director of public prosecutions, "with a view to giving a response within a month if at all possible".

Senior legal figures were concerned this could undermine the criminal justice system, with the attorney general warning Northern Ireland Secretary John Reid in 2002 that it could not become an amnesty.

Joint proposals in May 2003 by the British and Irish governments about dealing with On the Runs did not receive enough support to be implemented. These were published amid efforts to get the IRA to destroy its weapons, something that was independently verified two years later.

Anti-decommissioning graffiti in west Belfast from 2000

In 2006, an attempt to introduce legislation was shelved in the face of widespread opposition. Sinn Féin's rejection of it, because it would have also covered the Army and police and those guilty of collusion in crimes, made it unworkable.

Another secret letter from Mr Blair to Mr Adams in December 2006 outlined mechanisms to resolve outstanding On the Run cases, including "expediting the existing administrative procedures".

In February 2007, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) began a review of people regarded as "wanted" in connection with terrorist-related offences before the Good Friday Agreement, and what basis, if any, they had to seek arrests.

The then secretary of state, Peter Hain wanted the scheme to be run in secret. The PSNI had prepared a statement for journalists, should the scheme get into the public domain, but the work was never disclosed.

How did it become public knowledge?

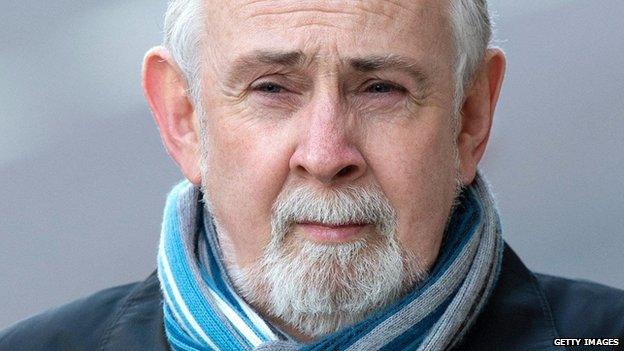

John Downey received an assurance he would not face prosecution

The details only became more widely known in February 2014 when a case against a suspected IRA bomber collapsed at the Old Bailey.

County Donegal man John Downey was to go on trial charged with killing four soldiers in the 1982 IRA Hyde Park bombing.

However, he cited an official letter he had received in 2007 saying: "There are no warrants in existence, nor are you wanted in Northern Ireland for arrest, questioning or charging by police. The Police Service of Northern Ireland are not aware of any interest in you by any other police force."

The judge ruled that Mr Downey, who denied any involvement in the bombing, should not be prosecuted because he was given a guarantee he would not face trial.

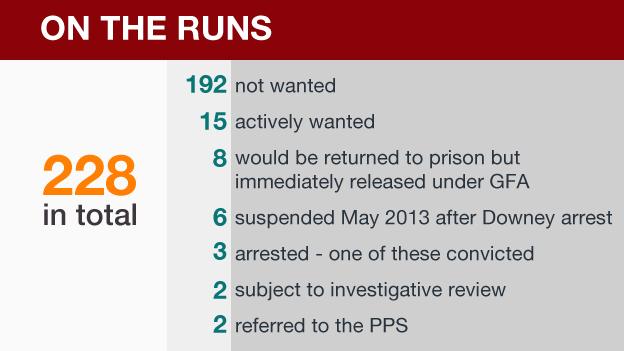

Mr Justice Sweeney heard from Sinn Féin's Gerry Kelly that 187 people had received letters assuring them they did not face arrest and prosecution for IRA crimes.

The Northern Ireland Office issued the assurance on receipt of information from the PSNI, but while they soon realised he was still wanted by colleagues in Scotland Yard over the Hyde Park bombing, the letter was never withdrawn.

The Crown Prosecution Service had argued that the assurance was given in error - but the judge said it amounted to a "catastrophic failure" that misled the defendant.

What happened next?

David Cameron: Downey "should never have received the letter"

The news that Mr Downey would not face trial prompted an immediate outcry, with Prime Minister David Cameron telling the Commons that the letter he received in error had been a "dreadful mistake".

Three separate inquiries were launched:

Court of Appeal judge Lady Justice Hallett was appointed by the government to produce a full public account of the operation and extent of the scheme to determine whether any letters contained errors

The Northern Ireland Affairs Select Committee began its own inquiry, holding a series of public hearings

Police in Northern Ireland began a review of the process that led to the issuing of the letters, with a team of 16 detectives investigating the circumstances of each of those who received a letter, and re-examining the original checks by a specialist PSNI team that led to the Public Prosecution Service being told none of the individuals were wanted.

What questions were the NI Affairs Committee trying to answer?

The committee took evidence from a range of figures

The committee announced its own inquiry, external into the scheme as MPs said they were concerned that the one commissioned by the government, led by Lady Justice Hallett, was too narrow in its remit and would not be held in public.

The committee examined a number of key questions:

What is the background to, and origins of, the scheme, and what was its purpose and intended effect?

Who constitutes an On the Run, and what are the legal implications of the scheme?

What are the political implications of the scheme and were errors made?

What impact has the scheme had on victims and relatives?

Who gave evidence to MPs during the NI Affairs Committee's inquiry?

Tony Blair apologised for not putting in place a structure that would have prevented an error being made in the On The Runs letters scheme

Former prime minister Tony Blair was the most high-profile witness to give evidence, telling the committee that the Northern Ireland peace process would have probably collapsed without the On the Runs scheme.

Other witnesses included former Northern Ireland secretaries Peter Hain and Paul Murphy, current and former senior police officers, former detectives involved in administering the scheme and relatives of victims of the Troubles.

Sinn Féin representatives declined to appear before the Westminster committee, saying that the party had already met Lady Justice Hallett's review team.

What were the committee's conclusions?

The committee's hearings were held in the Houses of Parliament

The parliamentary watchdog found that the "one-sided, secretive scheme of letters" had damaged the integrity of the criminal justice system and should never have existed.

In their report, the MPs said the people of Northern Ireland had been "kept in the dark to the greatest possible extent". The committee said the lawfulness of the letters was questionable.

It recommended that all steps should be taken to ensure that OTR letters have no legal effect.

The report also accused the Irish government of "trying to persuade HM government to introduce an amnesty for republican terrorist suspects".

It said that if the PSNI had known about the entire scheme and had been involved in checking letters sent to OTRs, then "it is almost certain that the Downey judgment could have been prevented".

It also stated that the availability of the scheme to one section of the community "at the whim of one political party" raised questions about equality rules in Northern Ireland.

Committee chairman Laurence Robertson said victims of the Troubles and their relatives had been "let down" by the government, and the scheme had caused "further hurt to people who have suffered far too much already".

Does it go further than the Hallett inquiry?

Lady Justice Dame Heather Hallett found 'significant systemic failures' in how the scheme operated

While the NI Affairs Committee's hearings were public, Lady Justice Hallett's inquiry was held in private.

Downing Street said the terms of reference of her review were to produce a full public account of the operation and extent of the scheme to determine whether any letters contained errors.

The judge was able to seek to interview anyone, but she did not have the power to compel witnesses to attend. It could not alter the decision not to appeal the Downey case.

In her report, external, published in July 2014, the judge said the letters were not an amnesty and the scheme had been lawful.

However, she found "significant systemic failures" in how it operated, and the letter to Mr Downey was the result of a "catastrophic mistake" by the PSNI.

"The administrative scheme was kept 'below the radar' due to its political sensitivity, but it would be wrong to characterise the scheme as 'secret'," she said.

There was enough information in the public domain for anyone keeping a close eye on Northern Ireland affairs to have known there was such as scheme, she said.

The judge said she had "detected no sinister motive in the failure to notify the minister for justice, the first minister and the Policing Board of the scheme".

"The hope seems to have been that the scheme could be brought quietly to a close without generating the kind of controversy we have seen in recent months.

"Whether that was a wise policy is for others to decide."

So after all this, is the scheme still going on?

Northern Ireland Secretary of State Theresa Villiers said a month after the John Downey case collapsed that since December 2012, no letters have been issued by the Northern Ireland Office.

Five outstanding applications from republican suspects would not be processed by the government, she said.