The Last Minyan: The decline of Belfast's Jewish community

- Published

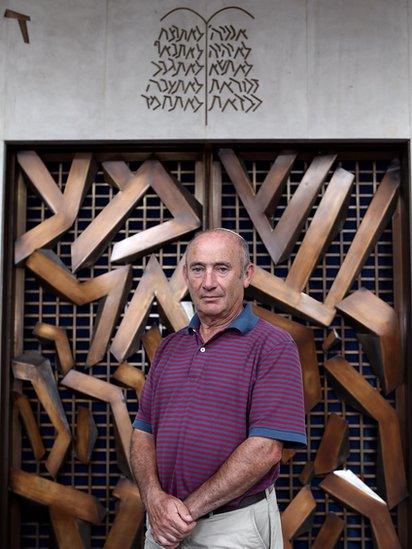

Belfast Jewish Community chairman Michael Black regularly struggles to find 10 men - known as a minyan - to take part in synagogue services

Standing at a graveside in Belfast, Michael Black foresees a bleak future for the city's once-thriving Jewish population.

"The big problem is, will there be enough people here to bury the last few?" he asks.

As chairman of the Belfast Jewish Community, Mr Black takes the burden upon himself to help keep the old traditions alive and keep what is left of an aging community together.

Jews first began arriving in Northern Ireland in the 1860s. Hailing mainly from Germany, they were attracted by Belfast's booming linen trade.

At its peak, the Belfast Jewish Community had about 1,500 members, and fostered a future Israeli leader, Chaim Herzog, who became the sixth president of Israel in 1983.

But these days, the community's membership has fallen to fewer than 80 people.

Chronic shortage

Their dwindling numbers have made it even more difficult for the few left behind to observe Jewish customs and ceremonies, and it is not just the lack of kosher food that causes problems.

It is difficult to attract a rabbi to minister to such a small congregation; it is a formidable challenge to meet a Jewish spouse in the city and - even if you find love within the faith - it is impossible to send your children to a Jewish school in Northern Ireland.

For Mr Black, these days it is a regular headache just to find 10 Jewish men to take part in a religious service - the minimum number required for public worship to take place.

The proper term for these 10 men is a minyan and it was Belfast's chronic minyan shortage that provided the inspiration for a new BBC Northern Ireland documentary.

The Last Minyan - A Belfast Jewish Story, was filmed, produced, and directed by Mr Black's son, Aaron, as part of BBC Northern Ireland's True North document series.

Belfast's Jewish Community has struggled to recruit a spiritual leader, but the post is currently held by Rabbi Singer

Although raised as a Jew, the filmmaker says he "was never religious" and, like many of his peers, stopped going to the synagogue many years ago.

But having recently become a father himself, Aaron Black wanted to go back his roots, reconnect with the small society he left behind as a teenager, and find out just how important it was to him that his culture survived into the next generation.

Pressure

As the film progresses, it is clear that the community is not just a few men short of a full minyan.

"Where are all the women in the Matthews household?" the filmmaker asks, as one of Belfast's last Jewish families sit down to a Sabbath meal.

"Obviously being Jewish, I would very much have liked to have had a Jewish bride, but things didn't happen," Alan Matthews replies.

He and his peers felt the pressure of expectation to marry within their faith, but also the discomfort of growing up within a small, close-knit society, where most of the women were their childhood friends.

The Matthews family share their experience of trying to keep the faith in Belfast

Belfast is a city scarred by decades of sectarian division, and although the outbreak of the Troubles did not exactly help the expansion of its Jewish population, it does not fully explain its decline.

The programme suggests that the Belfast exodus was more to do with a lack of romance - the poor prospect of meeting a Jewish partner - rather than fear of sectarian violence.

"What happens in close communities is that you know each other too well," says Aaron Black.

"These people, even if they weren't related, they probably felt more like cousins and it just wasn't conducive for marriage."

Virtual classmates

Moving forward into the next generation, the situation deteriorates even further.

Orthodox Rabbi Brackman brought his young family to Belfast a few short years ago, but as there are no Jewish schools in the city, his children are taught at home, taking their lessons via the internet.

As his son's teacher appears on a small screen all the way from New York, the child's mother appears to struggle with the couple's internet connection.

There are eight pupils in the boy's online class, but exactly where in the world the other children are based is not made clear.

Virtual school friends are no substitute.

"There are actually no other kids physically around him. He needs to speak to other boys," says his concerned mother, Ruth Brackman.

It is not long before her family are packing their bags and Belfast is searching for a replacement rabbi.

Michael Black is set the task of finding a new spiritual leader who can cope with both the tide of secularism and Belfast's minyan drought.

Family over faith

Despite his weekly battle to find volunteers, it is revealed that Mr Black has never asked his own son to help make a minyan.

Aaron says this is because his family would never have put pressure on him to take part in religious ceremonies, but now, 20 years on, he wonders if his father should even have had to ask.

The filmmaker is now a weekly visitor to his local synagogue, but insists his reconnection to his Jewish heritage is less about religion and more about family roots.

"It's not a film about faith," he says. "I think it's a film about family. It just so happens that these families are bound by a shared history."

His personal journey back through his own family history has helped to understand more about Judaism as a culture and the importance of preserving its customs.

"I wanted to focus on the realities of keeping this tradition alive under difficult circumstances.

"This is something that is happening across the the UK. I knew that Belfast is struggling and I wanted to document this world before it was too late."

True North: The Last Minyan - A Belfast Jewish Story will be broadcast on BBC One Northern Ireland on Monday 10 March at 22:35 GMT.