Sketching history: Is the cartoonist's pen mightier than the sword?

- Published

Cartoonist Graeme Keyes satirising the 'Ulster says no' slogan

During the Troubles in Northern Ireland political cartoons played a key role in depicting the violence.

But what was it like for the cartoonists whose job it was to satirise the atrocities?

The Troubles

The late Rowel Friers had been publishing cartoons from 1948, with his Belfast Telegraph column initially comprising loosely news-based cartoons.

But Friers' life was indelibly changed when the Troubles began in Northern Ireland in 1969, as he described in a 1994 BBC interview.

"When I started out it was general humour. But once the Troubles broke out we were in hell and I had to turn to the political scene, which frankly I had no interest in.

"I had no political leanings - the only side I took was sanity. I had no bias whatsoever, so I could criticise all round me."

Friers, who was known for his witty and insightful cartoons, spoke of the threats he received:

"At the beginning I got all sorts of threatening letters and phone calls. But it all settled down because people could see I was preaching peace and common sense."

Emotional impact

In the same interview Friers recalled how the Troubles took the humour out of some of his cartoons.

Rowel Friers depicts the IRA bombing of the La Mon hotel in Belfast in 1978

"Some of my cartoons were so morbid people thought I must be a terribly heavy, morbid person. I'm not really but things like the La Mon hotel bombing were so horrific that they're bound to affect you," he said.

"So when you're drawing them, you feel way down and horrified, and you put all you've got into this cartoon."

For Ian Knox, a veteran cartoonist with the Irish News, it has always been important, as far as possible, to retain the humour in the cartoon.

"While retaining consciousness of victims I try to be amusing. Funny cartoons are taken seriously. Morbid ones aren't," he says.

Ian Knox's depiction of David Trimble, Ian Paisley, John Hume and Gerry Adams in the 1990s

In an interview with The Detail earlier this year Knox reflected on how he dealt with the sensitivities of the latest atrocities and the pain of grieving families:

"It was always hovering behind my shoulder but I never shrank from any issue. The day I have to shrink from an issue I'll pack it in. I think violence is the worst sin there is. I've never been criticised by victims as they respect that I'm seeking the truth."

Knox, who features in the latest episode of BBC Northern Ireland's The Arts Show, believes that while political satire is vital in holding politicians to account, he ruefully reflects on its inability to change the politicians.

"Ridiculous figures who should long since have been laughed into obscurity still strut the political stage and get re-elected and re-elected," Knox says.

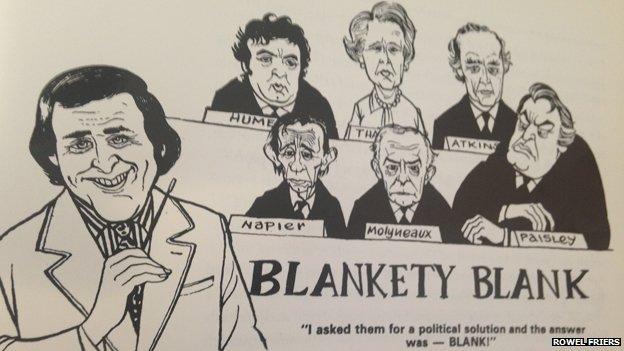

Rowel Friers depicts the lack of a political solution in the 1980s

Bobby Sands

In his 1994 autobiography Drawn From Life Rowel Friers recalled the experience from the Troubles that had the most profound impact on him.

"Of the many melancholy and deeply depressing incidents I have been impelled to comment on, few have left such a shadow on my mind as the death of Bobby Sands. It was a chapter of history which had to be recorded and it was my lot to make that recording."

Ian Knox discusses the art of political satire with The Arts Show's Darryl Grimason

After IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands' death in 1981 Friers received a call from an American TV executive asking him to go to Sands' house where his body was on display for mourners to pay their respects.

After returning from the house, Friers was then to draw an artist's impression of Sands for American TV.

Friers described his feelings as he got to the coffin, which was guarded by two armed black-uniformed men, wearing dark glasses.

"The head on the pillow paralysed me, and mixed emotions of horror and deep pity swept through me. This was the face of an old man, more than that, it was the face of death itself.

"Anyone who saw him as I did will never forget Bobby Sands because they will know how hellish the suffering he had endured must have been."

In a 1994 BBC television interview with Sean Rafferty, Friers discussed how the emotional impact of reporting on incidents throughout the Troubles contributed to him having a mental breakdown.

"It was a big part of it. The whole 25 years of heavy atmosphere and mayhem has got to affect you when you're dealing with it as a newspaper man," he said.

What makes a good cartoon?

Rowel Friers used a Miss World beauty pageant to highlight the case of three women in Londonderry who had been tarred and feathered for socialising with British soldiers

Ian Knox explains what a cartoon aims to do: "A good cartoon should entertain, it should divert and it should maybe cause a slight frisson of perception in the viewer, causing them to think 'ah that's true - I never thought of it quite like that'."

Knox considers a fantasy world to be important in a political cartoon.

"People like to be taken slightly away from the grim reality into a slightly different kind of grim reality," he says.

"I always hoped my mirror to the world would be really distorted. I'm a distorter of the truth and a bringer of the truth. But I do it through distortion."

Knox is adamant satire is about getting at the truth.

"Although you may go overboard to caricature it, you're not trying to come up with something that isn't the truth," he says.

"I try to be as wild and strange as possible, while keeping the meaning. The key is capturing what makes the person unique."

Speaking in 1994, Rowel Friers explained the power of a political cartoon:

"A political cartoon is a very potent weapon because people will see it and the whole situation can be summed up in one line, or in no lines at all."

President Clinton and Gerry Adams

Ian Knox says he rarely receives complaints about his cartoons, but there was a notable exception to this in 1994, when Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams received a visa to enter the United States after having been banned for years due to Sinn Féin's political links with the IRA.

Ian Knox cartoon on Gerry Adams being granted a US visa in 1994

Knox reflects on the outcry his cartoon about the incident caused.

"The switchboard at the Irish News was inundated with complaints for a week and people said they were outraged because it was a family newspaper and it betrayed all its principles," he says.

"Nothing like that has happened since unfortunately! I've had plenty of writs but no days in court."

Northern Ireland political archive

Belfast's Linen Hall Library, external houses a vast political satire collection, including cartoons of the Irish Rebellion of 1798. John Killen, chief librarian at the Linen Hall Library, believes political satire has played a key role in reporting events in Northern Ireland.

"Cartoons provide a stellar archive of the political situation in Northern Ireland because they were being produced on a daily basis and covered all the issues. Political cartoons held a mirror up to daily life in a divided society," he says.

"The cartoonist wasn't setting out to change the situation but he was feeding into the debate and informing people, explaining who we are and what we're doing."

Unlikely political bed fellows: Northern Ireland's Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness and First Minister Peter Robinson

So what role can cartoonists play in reporting on a conflict?

Ian Knox feels satire is unique.

"Visually depicting the true motives and interests of devious and manipulative operators is somehow perceived as more credible than writing about it.

"The cartoonist who makes the same point as the columnist is credited with more common sense."

Knox believes political satire will continue to be hugely relevant given the fear it causes among those in power:

"Fundamentalists and dictators through history have feared the ridicule of the satirist more than the military might of opponents.

"Top of Hitler's list of those to be dealt with if The Nazis invaded Britain was cartoonist David Low!"

This episode of the Arts Show is available to watch on the BBC's iPlayer until 28 April 2014.

- Published11 April 2014