A life in conflict: How Peter Taylor gained the trust of paramilitaries

- Published

"I was driven in the dead of night, hidden under a blanket in the back of a car. I was taken to meet the IRA at a secret location where I had to listen to the taped 'confessions' of three alleged informers whom the IRA said were British agents. They had previously been executed and their bodies left at the side of lonely country roads."

Veteran journalist and broadcaster Peter Taylor is reflecting on a particularly perilous experience reporting on the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

After more than 40 years reporting conflicts throughout the world, Taylor has seen considerable danger and bloodshed.

His distinguished career led to him being honoured with a BAFTA Special Award on 26 September. He considers the award to mean more than simply personal recognition.

"This award is very special and not just recognition for me, but for all the incredible colleagues I've worked with, and all those people I've interviewed over the years, who have been the bedrock of my work," he said.

In recent years Taylor has devoted much of his time to reporting on al-Qaeda, but he continues to regularly cover Northern Ireland, where he has just been making the BBC Northern Ireland documentary Who Won the War? in which he gives his assessment on who the winners were in the conflict.

So what it is about the conflict in Northern Ireland that has led him to devote so much of his career to reporting on it, making close to 100 programmes on the subject, and how has he been consistently able to get paramilitaries on all sides to talk to him?

Bloody Sunday

Taylor's journey reporting on Northern Ireland began on one of the darkest days of the Troubles - Bloody Sunday on 31 January 1972. He arrived hours after soldiers had shot dead 13 civilians at a civil rights march in Londonderry. He did not know where Derry was and had little knowledge of what the conflict was all about.

"I was frustrated because the plan we'd had to cover the civil rights march that day fell through due to costs, so the coverage never happened. It was one of the great what ifs," he said.

"When I arrived, I remember feeling guilty that it appeared 'my' soldiers were being accused of shooting dead 13 innocent civilians and guilty at my own ignorance of the issues and history that lay behind the conflict."

"It was shortly afterwards that I first met Martin McGuinness in the disused gas works in the Bogside that served as the Provos' makeshift HQ. I recall him saying he would rather be cleaning the car on a Sunday and mowing the lawn than doing what he felt he had to do."

Taylor was immediately drawn into the conflict and driven to find out as much as he could about it, spending his summer holiday that year devouring books on Irish history on the beach.

He insists there was never any plan to devote so much of his career to Northern Ireland, but circumstances dictated it would be so.

"It just happened as the 'story' didn't go away over the next three decades, although I covered many other subjects, including Vietnam, South Africa and, in the wake of 9/11, al-Qaeda and Islamist extremism. In the same way my trilogy Provos, Loyalists and Brits just evolved, literally one series after the other."

"Dealing with Muslim extremists is exceptionally difficult. Generally unless they believe you either subscribe to or are sympathetic with their ideology, or at the very least are a Muslim, they will not be interviewed, or in some cases even talk to you."

For Taylor, the journalistic attraction of Northern Ireland was that the conflict was taking place in a relatively small geographical area and journalists had potential access to all sides.

"This meant journalists, if trusted, were in a unique position to make informed assessments on highly controversial topics like police interrogation and the so-called 'dirty war'. Organisations such as the IRA were aware of the value of publicity, whereas now groups such as al-Qaeda use the internet as a vehicle for getting their message out," he said.

Gaining trust

So how did he go about gaining the confidence of paramilitaries, to ensure they would speak to him?

"Trust is the key and it takes years to build it up. In the end you are judged by what you say you will do and what you actually do. There has to be a correlation between the two," he said.

He would often go back to talk to all sides after programmes for face-to-face meetings to discuss whether he had done what he said he would do. Generally, there was agreement that he had, although naturally not everyone was happy with everything.

"There was/is a general recognition that I have a job to do and that job crucially involves being fair. When I'm in Northern Ireland, it means a lot when from time to time I'm stopped by people from both sides who say 'thank you for being fair'. It's quite a humbling experience."

Was it difficult to ask hard questions of paramilitaries, and not appear judgmental, particularly after they had carried out acts he may personally have found to be deplorable?

Peter Taylor stands in front of a mural of IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands

"This was always the finest and most difficult line to walk. I was conscious that I had to confront them with the tough questions that I knew viewers would want and expect me to ask, and I wanted to ask too. In most cases, my interviewees knew I had a job to do and respected it, although there were some difficult moments", he said.

"On a couple of occasions I felt my interviewees were on the point of walking out, and that could have jeopardised all the other interviews I was hoping to do. Building some kind of relationship and rapport is always essential, despite what the interviewee may have done."

Taylor explains what motivated him when speaking with paramilitary organisations in Northern Ireland:

"I've always tried to understand why ordinary people, on both sides, are prepared to do the most horrific things. I've been careful about not being seen to give the so called oxygen of publicity to the organisations. My questioning of them has always been, I think, fairly robust."

Legacy of the Troubles

Having experienced so many atrocities during the Northern Ireland conflict, Taylor says it is difficult to judge which has had the most lasting impact upon him, although he does highlight some significant moments:

"Obviously Bloody Sunday was the seminal event for me, as it was for Northern Ireland. Bloody Friday [on 21 July 1972, when the IRA exploded 19 bombs across Belfast in 80 minutes] had a similar effect."

Meeting Brendan Duddy, external for the first time and spending most of the night listening to his story about being a secret intermediary between the IRA and British intelligence services proved hugely significant to Taylor, as did meeting the victims of the Enniskillen bomb for his Age of Terror series.

A recent encounter also had a profound impact on him when he tracked down Sean McKinley for the Who Won the War? documentary, 40 years after he had interviewed him in Belfast's Divis Flats in 1974.

Sean McKinley appearing in Peter Taylor's 1974 documentary on Divis Flats

The then 12-year-old boy told Taylor that he wanted to fight and die for Ireland when he was older. In 1987 McKinley was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of a British soldier.

Long road to peace

As for Northern Ireland today, Peter Taylor considers it unrecognisable from the country he first encountered over 40 years ago. But he believes that while much progress has been made, there is still work to be done.

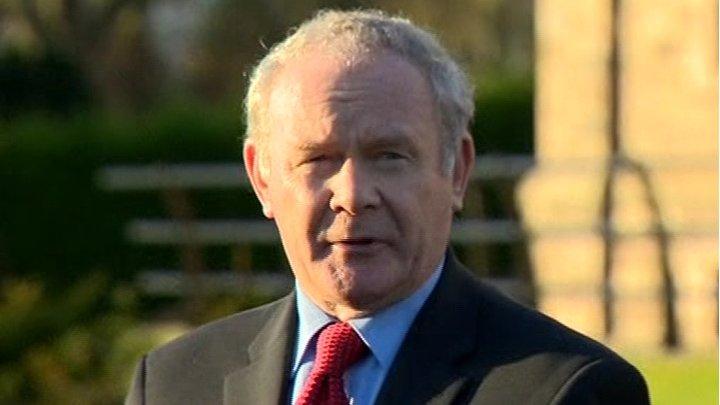

The Queen and Martin McGuinness shake hands in June 2012

"In some places normality seems a veneer to hide the powerful undercurrents of bitterness and resentment that have never gone away," he said.

"The peace may be imperfect with issues that remain unresolved, like flags and parades, but at least it is a peace that I would never have imagined, any more than I ever imagined the sight of Ian Paisley sharing power and laughing and joking with his sworn enemy, Martin McGuinness."

"The former IRA commander Martin McGuinness having an audience with the Queen as deputy first minister is an astonishing illustration of how far things have come."

Watch the documentary Who Won the War?

- Published26 September 2014

- Published26 September 2014