Famine misery 'targeted Ulster's Catholic and Protestant poor'

- Published

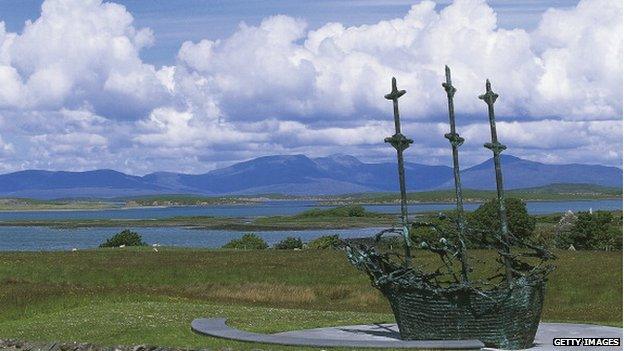

A monument in Dublin to those who suffered in the 1845 Irish famine that became known as the Great Hunger

Ireland's Great Hunger did not discriminate.

The famine of 1845 targeted both the Irish Catholic poor and the Protestant poor in the north of the country, a historian has stressed.

The pioneers of a new cross-community project in Belfast are out to shatter myths and raise awareness about the shadow cast by the famine across Ulster.

Sharing the Past is an initiative that brings together people from the city and from Larne to look at how the poverty and the cholera, typhus and dysentery that came in the wake of the potato blight affected everyone.

Across Ireland, about one million people died in the famine and a further 1.5 million emigrated to Canada, America and England. Many died of typhus on the "coffin ships".

The National Famine monument, a sculpture of a coffin ship, is at the foot of Croagh Patrick in County Mayo

As part of the project, historian Dr Francis Costello will lead a lecture series on the Great Famine. He is currently writing a book on the global impact of the hunger.

Community groups will visit old workhouses and sites on both sides of the border associated with the famine.

"What is rewarding about this project is that it is driven by the grassroots up. There are very harrowing stories about people's ancestors from Larne and the Shankill," Dr Costello said.

"This is education from the ground up that breaks down the myths and the shibboleths surrounding the famine. Ulster - all of it - was hit very badly, not just Donegal."

Dr Costello said that by 1846 one in five people in Belfast had been affected by some sort of contagion linked to the famine.

Hungry people flooded in from the Ards peninsula and disease spread easily in the tenement houses.

The linen industry went into a decline because of the sickness: "It was a calamity that struck across all classes and all faiths and no faiths," he said.

But through all the suffering, there was a kindness and a willingness to help.

"In Howard Street in Belfast, the local merchants fed 2,000 people a day at soup kitchens. The Society of Friends, the Quakers, did tremendous work and butchers and vegetable growers helped," he said.

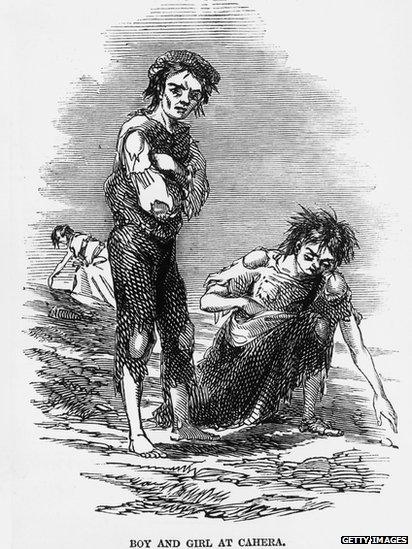

1846: A starving boy and girl rake the ground for potatoes at Cahera during the Irish potato famine

"In Belfast, then with an overwhelmingly Protestant population, the evidence shows there was a rekindled ardour of the early Christian Church characterised by charity and alms and the desire to alleviate starvation and illness.

"This saw people across traditions and classes coming together to support the poor."

The project's organiser, Building Communities, is being supported by a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Stafford Reynolds of Building Communities said: "The project will explore how the events surrounding the Great Famine and the social history of that period impacted on people from all communities and that poverty and disease did not discriminate in who it affected. We cannot aspire to a shared future, if we don't first develop a shared understanding of the past."

At the end of the research, the community groups will publish a series of small booklets. They will also develop an exhibition on the famine.

The project is beginning in Belfast and Larne, but could be extended across Northern Ireland.

"The Irish case is unique, but that misery and human toll was not unique to one part of the community," said Dr Costello.

- Published7 January 2015

- Published21 May 2013