Comparing the evolution of IS and the IRA

- Published

The seeds of IS were sown at a detention camp in southern Iraq

There is a remarkable parallel between the rise of the so-called Islamic State (IS), and the evolution of the IRA in Northern Ireland, says the BBC's Peter Taylor, who covered the conflict for over 40 years.

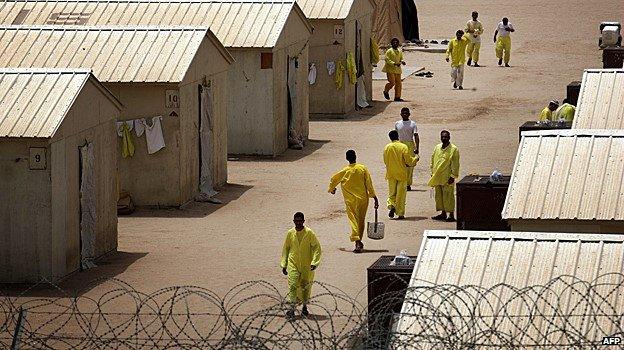

The force of the comparison hit me when I was recently in Iraq investigating where and how the leadership of IS came together, for a BBC Two This World documentary. It was forged in a most unlikely place, an American internment camp in the sands of southern Iraq called Camp Bucca, named after Ronald Bucca, a New York fire fighter killed in the 9/11 attacks.

Over 20,000 suspected Iraqi insurgents - mostly Sunni - were incarcerated there until its final closure following the US withdrawal from Iraq in 2011.

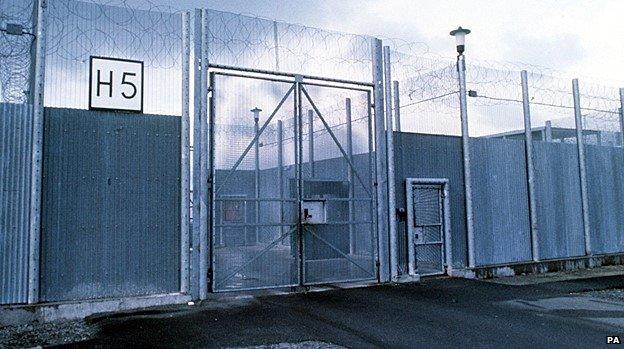

Key elements of the IRA's leadership also came together three decades earlier in an internment camp in Northern Ireland known as Long Kesh. Camp Bucca and Long Kesh have entered the folklore of the two insurgencies.

Both camps looked the same with detainees locked up in prisoner of war type compounds surrounded by high wire fences. Inside both Iraqi insurgents and Irish republican prisoners enjoyed almost total freedom to organise and devise blueprints for their respective futures.

Inmates at Camp Bucca were locked in prisoner of war type compounds

In Long Kesh the IRA mapped out its long-term political and military strategy known as "the long war". In Camp Bucca the future leadership of the so-called Islamic State devised the blueprint for its fearsome army and draconian "state".

Camp Bucca detainees spent endless hours studying the Koran and discussing military strategy in the privacy of their huts. One of them, who allegedly tried to assassinate the governor of Baghdad, told us, "the inmates didn't have much to occupy their minds. They felt cornered and oppressed - the perfect environment for anyone with an ideology which challenges the oppressor".

General David Petraeus, Commander Multi-National Forces Iraq 2007-8, whose "surge" against IS's predecessor, Al Qaeda in Iraq, helped fill up the compounds even more, told us, "these extremists were basically running a terrorist training university, or at least a radicalisation school, in our own detention facilities." Ironically at Camp Bucca the Americans unwittingly created the conditions in which the seeds of the so-called Islamic State were sown.

Most of IS's future leadership were Camp Bucca alumni, including its leader and self-proclaimed Caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. General Petraeus - on whose radar al-Baghdadi never figured - became increasingly aware of the growing problem inside the camp and tried to stem the tide of radicalisation that boded so ominously for the future.

"I'd stopped the release of detainees," he said, "because I felt that we were actually releasing individuals who were more radical than they were when they entered." But the tide proved unstoppable.

IRA prisoners trained using wooden weapons at Long Kesh prison near Belfast

Long Kesh received the sobriquet of "terrorist university" long before Camp Bucca. IRA prisoners did military training with wooden weapons, devoured revolutionary treatises, held intense debates about the "armed struggle" against "British occupying forces" as well as spending time rioting, digging escape tunnels and attempting to burn down the camp - all of which were mirrored in similar events at Camp Bucca.

Support for the IRA and the so-called Islamic State also has remarkable similarities, not least because both represent minorities in divided communities. The IRA's support base lies in Northern Ireland's Catholic/Nationalist community, whilst in Iraq the so-called Islamic State draws support from the minority Sunnis.

When the "Troubles" in Northern Ireland erupted in 1969, many Catholics looked to the IRA to defend them from attacks by loyalist gangs, the predominantly Protestant police (the RUC) and the British Army.

Support for the IRA grew after "Bloody Sunday" on 30 January 1972

Similarly in Iraq after Camp Bucca was emptied and the Americans withdrew, many Sunnis looked to the so-called Islamic State as their defenders from attacks by the Shia dominated security forces and so-called "death squads" that were the instrument of the predominantly Shia government.

Sunnis were meant to have a power sharing role in the new government under the Shia Prime Minister, Nouri al-Maliki, elected after the American withdrawal, but Maliki soon turned on his Sunni partners, further alienating the community they represented. The Sunni Vice-President, Tariq al-Hashemi, was accused of terrorism and now lives in exile under sentence of death.

Charles Farr, the UK's director of the Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism, has no doubt about the result of the sectarian targeting of Sunnis by the Shia dominated government. "[IS] succeeded in convincing Sunnis, who are oppressed by the Shiite governments of Iraq and Syria, that they have taken up their cause and that they are the ones who will stand up for them. Some of them regarded Islamic State as a potential source of security."

And there's a final bloody comparison in massacres that greatly increased support for both the IRA and IS. On 30 January 1972, a day forever known as "Bloody Sunday", British paratroopers shot dead 13 unarmed [See note below] Catholics on an anti-internment march in Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It was the first great watershed in the conflict and drove hundreds of young Catholics into the arms of the nascent IRA.

The coffins of the 13 civilians shot dead on "Bloody Sunday" lined up for the funeral

Nearly 40 years later Prime Minister, David Cameron told the House of Commons that he was "deeply sorry" and said the findings of Lord Saville's 12 year inquiry into the killings were "shocking".

In Iraq dozens of Sunni Arabs were shot dead in 2013 by predominantly Shia security forces at Hawija, a village near Kirkuk. The demonstrators had set up camp to protest against what they saw as their victimisation at the hands of the Shia dominated government. Estimates of the death toll vary from 20 to over 40. The government said their forces came under attack from gunmen and had to respond.

Ironically the British army said the same at the time of "Bloody Sunday". The now exiled Sunni Vice President, Tariq al-Hashemi, told us that "people are losing hope" and many young Sunnis "daily join forces with IS". The Hawija killings had a profound impact on the Sunni community just as "Bloody Sunday" did on the Catholic community in Northern Ireland, driving many into the arms of the IRA and IS.

But there is one key difference in the evolution of both groups. The IRA is no more, having declared a ceasefire, decommissioned its arms and in a remarkable political accommodation, entered a power sharing government in Belfast with its old enemies.

The so-called Islamic State has no intention of sharing power with anyone, let alone the Shia. To its 7th Century ideology, the Shia are infidels and there to be killed. That is where the similarities end.

The Saville Inquiry concluded that none of the victims was armed "with the probable exception of Gerald Donaghey". The 17-year-old's body was later photographed at an army camp with four nail bombs. There were allegations by his family and others that they had been deliberately planted on him.. Saville disagreed. But the inquiry added: "We are sure that Gerald Donaghey was not preparing or attempting to throw a nail bomb when he was shot; and we are equally sure that he was not shot because of his possession of the nail bombs. He was shot while trying to escape from the soldiers."

This World: World's Richest Terror Army will be broadcast on BBC Two on Wednesday 22 April at 21:00 BST, or catch up via BBC iPlayer.

Find out more: Peter Taylor tells the story of IS, the world's richest terror army

- Published2 December 2015