Brian Carberry: Man seeks compensation over contaminated blood scandal

- Published

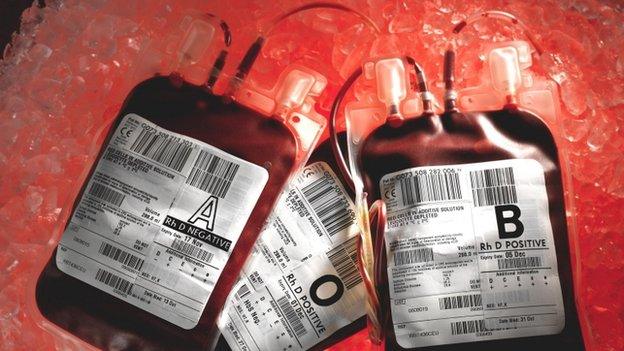

Up to 6,000 people in the UK have been identified as having contracted hepatitis C because they received contaminated blood products to treat their haemophilia in the 1970s and 1980s

A County Down man who contracted hepatitis C because he was given contaminated blood has said he is seeking compensation from the UK government.

Brian Carberry, 49, from Downpatrick, received haemophilia treatment as a child in the 1970s.

In the 1970s and 1980s, some blood products used to treat the disease were imported from the US.

They included donations from prisoners, who were at risk of hepatitis C or HIV.

Mr Carberry was one of about 6,000 people across the UK who became infected with hepatitis C because of the contaminated blood that they received. More than 1,500 others were also infected with HIV, the virus that can lead to Aids.

Some countries, including the Republic of Ireland, have compensated all those who received contaminated blood.

'Accept responsibility'

Mr Carberry said he cannot work because of his condition. Haemophilia is a rare inherited bleeding disorder in which the blood does not clot normally.

He said he suffers from irritability, depression, joint problems and is 20% more likely to develop liver cirrhosis.

"It's not necessarily about claiming, the government has acknowledged but they haven't accepted responsibility," he said.

Brian Carberry said the government should provide the same level of compensation for all victims, no matter what stage their illness is at

An independent, privately-funded inquiry into what led to the blood products being contaminated was carried out in 2007, external, but the UK government has never held an official investigation into what happened.

Successive governments have set up five different trusts to make financial support to patients who were treated with the blood products.

The schemes provide different levels of payments - one for individuals who develop chronic hepatitis C, while those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer are eligible to receive a further second payment.

'Couple of years left'

However, Mr Carberry, who is still deemed stage one, told BBC News NI that the government should provide the same level of compensation for all victims, no matter what stage their illness is at.

"Payment schemes don't work, by the time you get to stage two you're on the last part of your life but you don't get anything until you reach that stage," he said.

"Part of me wants to move onto stage two so I get something, but I know if I move on to stage two I've only a couple of years left (to live)."

- Published25 March 2015

- Published15 January 2015

- Published15 January 2015