Penrose inquiry: David Cameron apologises over infected blood

- Published

Victims of Scotland's blood contamination scandal shouted "whitewash" at the inquiry's news conference

Prime Minister David Cameron has apologised on behalf of the British government to victims of the contaminated blood scandal.

It came after a Scottish inquiry described the saga as "the stuff of nightmares".

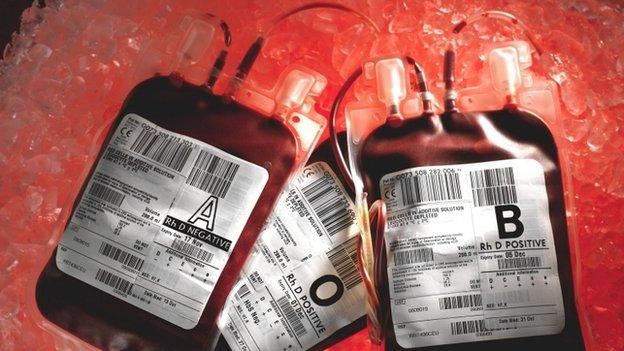

Thousands of people were infected with Hepatitis C and HIV through NHS blood products in the 1970s and 80s.

But the inquiry concluded few matters could have been done differently.

And it made only a single recommendation - that anyone in Scotland who had a blood transfusion before 1991 should be tested for Hepatitis C if they have not already done so.

There was an angry response to the report, external from victims and relatives who had gathered at the National Museum in Edinburgh to see its publication after a six-year wait, with shouts of "whitewash" after its conclusions were read out.

The contaminated blood scandal has been described as the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS, and was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of people, many of whom had been haemophilia patients.

It is hoped relatives find "some comfort" in Lord Penrose's reports

Hundreds of those affected were in Scotland, which was the only part of the UK to hold an inquiry.

Speaking at Prime Minister's Questions in the Commons, Mr Cameron said it was difficult to imagine the "feeling of unfairness that people must feel at being infected with something like Hepatitis C or HIV as a result of totally unrelated treatment within the NHS".

He added: "To each and every one of these people I would like to say sorry on behalf of the government for something that should not have happened."

He also confirmed that the government would provide up to £25m in 2015/16 to support any transitional arrangement to a better payment system.

Analysis

Hugh Pym, BBC health editor

The Penrose report is a detailed factual account of events over near two decades and a forensic examination of medical evidence and the detail of therapy with blood products. Blame is not apportioned, and perhaps Lord Penrose did not consider that was part of his remit.

But victims and families of those who died after receiving contaminated blood were unimpressed. At the end of the unveiling of the report in Edinburgh they heckled and shouted "whitewash".

The response to news that the Department of Health was providing an extra £25m in transitional relief was dismissed as a "joke" and "gesture politics" by one spokesman.

It is clear that they see this story as far from over and will continue to press for a full explanation of who was at fault and a comprehensive compensation settlement.

The scandal happened before the creation of the devolved Scottish Parliament, which now has full responsibility for the NHS in Scotland.

But Scotland's Health Secretary Shona Robison also apologised on behalf of the Scottish NHS and Scottish government to everyone who had been affected by the "terrible tragedy".

She accepted the inquiry's single recommendation on testing for those who had a transfusion before 1991, and said the Scottish government would review and improve the financial support schemes offered to those affected and their families.

Ms Robison added: "While this was a UK - indeed international - issue, I hope that today's report means that those affected in Scotland now have at least some of the answers they have long called for."

The probe, which was headed by former High Court judge Lord Penrose, said more should have been done to screen blood and donors for Hepatitis C in the early 1990s, and that the collection of blood from prisoners should have stopped sooner.

The full report runs to some 1,800 pages

Lord Penrose's inquiry took six years to complete its report

Patients were not adequately informed of the risks because of the paternalistic attitude of doctors at the time, it found.

But the inquiry concluded that nothing more could have been done to prevent the transmission of HIV.

And it said that when actions in Scotland were compared to other countries around the world, they held up well.

The inquiry also found that there were "few aspects in which matters could or should have been handled differently" and said the inquiry had to take into account the conditions that had prevailed at the time rather than judge by today's standards.

The inquiry had more than 13,000 pages of transcript, in addition to 200 witness statements and 120,000 documents, in its database.

Lord Penrose is seriously ill and was not present at the event, which opened with a minute's silence for those who had been affected.

'Broken lives'

A statement was read out on his behalf by inquiry secretary Maria McCann, who said patients in the late 1980s had been "confronted with the reality that what had been presented as a treatment to extend life and improve its quality carried a risk of serious and potentially fatal disease.

"The resultant distress, anger and distrust were clearly demonstrated to the inquiry."

There were shouts of "whitewash" from several members of the public who were present.

Bill Wright, from Haemophilia Scotland, begged people to stay to listen to him, saying: "This is by no means the end of the story."

One woman shouted: "We've shed enough tears."

Mr Wright said, sobbing: "I am one of you, I am infected."

The prime minister apologised to those who had been affected

He said of the report: "It's not about broken processes, it's about broken lives" and said now was the time for an apology.

Mr Wright added: "At first sight the report appears to disorganised and impenetrable. Worse still it might appear on first reading to be a whitewash with frankly some of the chairman's assertions seemingly barely rational.

"Look a bit deeper and there is a narrative setting out the case that cannot be avoided by the government and its moral responsibility."

He said there needed to be an "official apology", better compensation and a review of the report.

The inquiry's remit was to investigate how the NHS collected, treated and supplied blood.

Lord Penrose also scrutinised what patients were told, how they were monitored and why patients became infected.

- Published25 March 2015

- Published26 March 2015

- Published25 March 2015