Use of electric shock therapy without patients' consent rises in NI

- Published

BBC News Ireland Correspondent Chris Buckler's report on the use of electroconvulsive therapy.

The number of requests in Northern Ireland to use electro-convulsive treatment (ECT) on patients who have not given their consent has risen since 2012.

ECT involves passing an electric current through patients' brains, triggering a brief seizure in an effort to cure effects of extreme mental disorders.

Doctors, regulators and patients point to established and robust evidence to show that ECT works effectively and is safe.

However, there is a long expressed body of anecdotal evidence from patients unhappy with side-effects they say they've suffered after the treatment.

Severe memory loss, headaches and reportedly distressing personality changes are among the most common complaints. It remains a divisive medical technique.

The use of ECT is higher in Northern Ireland than in the reast of the UK

Most extreme disorders

Medical professionals don't yet fully agree on how exactly ECT works.

However they point to marked positive changes in the most challenging cases of depression, bi-polar disorder and schizophrenia after its use.

The vast majority of ECT treatment courses are chosen by the patients themselves. Sometimes however the shock therapy is administered without the patient's consent.

In order to do this in Northern Ireland, the second opinion of a senior psychiatrist appointed by the regulator is required under the Mental Health (NI) Order 1986.

In total, 96 patients in Northern Ireland were treated with ECT in 2014-15, both with consent and without.

The BBC has learned that within that year there were 53 referrals to carry out electroconvulsive therapy on patients without their consent.

This is up from the year 2011-12, when the figure was 36. In 2013-14 there were 55 such referrals.

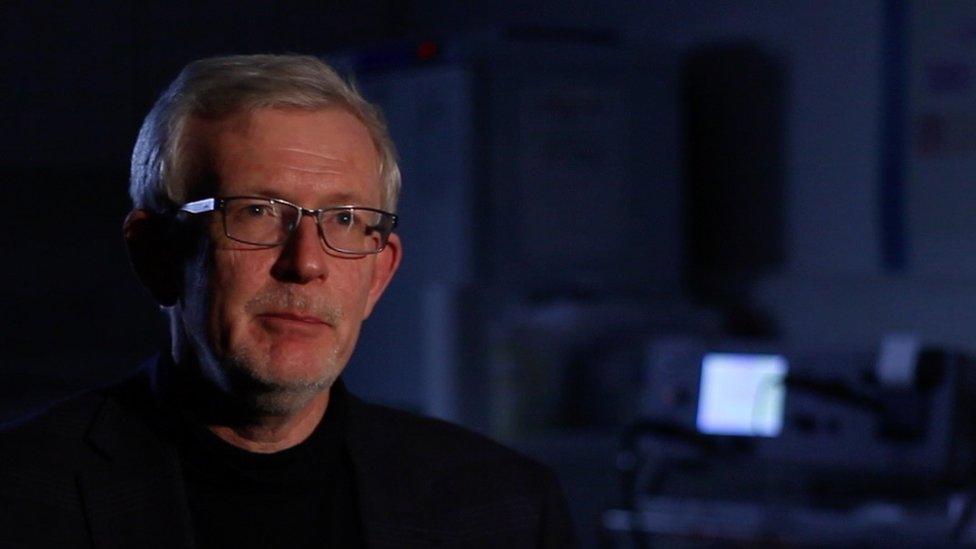

Dr Chris Kelly is a consultant psychiatrist, who says he has seen the difference ECT can make

Ability to consent

Dr Chris Kelly is a consultant psychiatrist highly experienced in ECT treatment.

He has seen the difference the treatment can make to patients who are given it without their consent. He said in most instances it has a beneficial outcome.

"Typically they tend to be individuals who are psychotic, who maybe have beliefs that they have caused harm, that they have got cancer when they don't have, these sorts of delusions," he said.

"I have looked after many individuals where we have had to keep them alive.

"The danger I think would be that you're asking someone whose ability to consent, their capacity to consent, is distorted by their depression.

"It is not a panacea, however. Selecting a treatment for your patient - well, that is the art of medicine. Selected wrongly, difficulties. Selected well, and these individuals can do remarkably well."

Mick Mulcahy was given electroconvulsive therapy against his will

Irish change

Mick Mulcahy is an Irish artist who was treated with ECT against his will in the Republic of Ireland. He says the legacy has been a traumatic one for him.

"You just don't want to be in your own body. [You think] this is not my body. I came in here healthy, without my permission. I don't deserve this. Who does?" he said.

In Ireland however new legislation is in the process of making its way into law which will make it impossible to give ECT in cases where people refuse to consent when detained involuntarily.

John Saunders, chairman of Mental Health Commission in the Republic, says that Northern Ireland should follow the south's in banning the use of ECT when the patient doesn't give consent

John Saunders is chairman of the Mental Health Commission in Republic. It pushed for the change.

"The worldwide international view would be that the person should consent to treatment and should not be in the situation where the law forces them to undergo treatment. If that is the case in Northern Ireland law, then I think there is a case for reviewing that.

"You should not have a situation where the state forces a particular treatment on somebody. There are arguments that some clinicians put forward, but there's always an alternative.

"You don't have to resort to ECT as a last option. There may be other medications. There may be other ways of dealing with situations."

He believes Northern Ireland should follow the Republic's change of law.

The Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority keeps referrals for ECT without consent in Northern Ireland under review.

In its most recent thematic report on the issue, it says ECT "is considered an important and necessary form of treatment for some of the most severe psychiatric conditions, and is, in some instances, a life-saving treatment".

- Published25 July 2013

- Published23 February 2014