Need-to-know guide: Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme

- Published

The RHI scheme brought Stormont's institutions to collapse in January 2017

What is the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme?

Back in 2011, the Northern Ireland Executive set itself two big targets on changing the way the region generated its heat, in an attempt to become more environmentally friendly.

It wanted 4% of Northern Ireland's heat consumption to come from renewable sources by 2015, with that figure increasing to 10% by 2020.

It set up the RHI scheme in November 2012 to help achieve those increases by offering a financial incentive to businesses and organisations to switch from using fossil fuels to renewable sources.

The scheme was run by Stormont's Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment (Deti), which later became the Department for the Economy (DfE).

A similar scheme had been in place in Great Britain but it was not fully replicated in Northern Ireland.

Hundreds of biomass boilers were bought and installed as a result of the scheme

How was the scheme meant to work?

Businesses and other non-domestic users were encouraged to ditch the fossil fuel-based heat generators on their premises and replace them with systems powered by renewable energy.

Those systems included biomass boilers, mostly burning wood pellets, as well as solar thermal and heat pumps.

The RHI scheme offered long-term financial support to those who signed up, in order to cover the cost of their new heating system and the fuel used to power it.

Users would receive a fixed amount of money for each kilowatt of heat energy their system would produce for a period of 20 years.

What was uptake for the scheme like?

Although Deti had set aside a £25m budget for the scheme between 2011 and 2015, uptake was poor and by the end of that period it had underspent by almost £15m.

The department focused on increasing the uptake, and applications for the initiative began to rise sharply in April 2015.

During the summer of 2015, officials decided that they would have to lower the tariff on offer if they were to meet demand for the scheme within its budget.

Some 984 applications were received in just three months - September, October and November 2015 - after officials drew up a plan to cut the subsidy but before the change took effect.

That spike in uptake added significantly to the overall cost of the scheme.

Subsidies paid out through the scheme were far higher than the cost of the fuels

How was the scheme exploited?

The RHI scheme offered to subsidise the cost of its claimants' fuel - mostly wood pellets - for running their heating systems.

But the fuel actually cost far less than the subsidy they were receiving, effectively meaning that users could earn more money by burning more fuel.

Northern Ireland's auditor general Kieran Donnelly said that there was "no upper limit on the amount of energy that would be paid for".

In one example cited in his 2016 report on the scheme, a business taking part in the similar initiative in Great Britain could collect about £192,000 over 20 years by using a boiler all year round.

But a Northern Ireland firm doing the same could earn £860,000.

How was the scandal exposed?

A whistleblower contacted Northern Ireland's first and deputy first ministers in January 2016 to allege that the RHI scheme was being abused.

One of the claims they made was that a farmer was aiming to collect about £1m over 20 years for heating an empty shed.

It was also alleged that large factories that had not previously been heated were using the scheme to install boilers with the intention of running them around the clock to collect about £1.5m over 20 years.

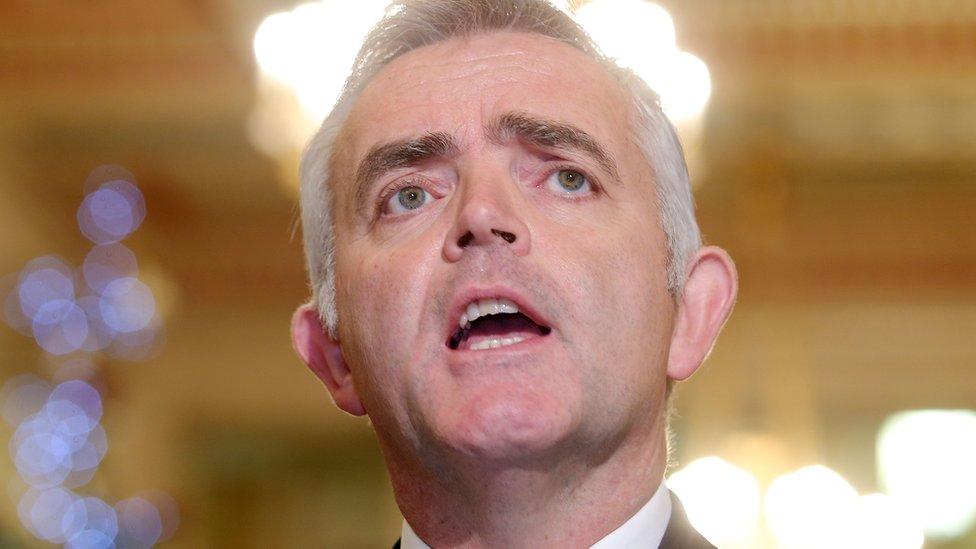

Jonathan Bell announced the scheme's closure in February 2016, citing its "significant financial risk"

When was the scheme closed?

The RHI scheme was shut down in February 2016 by the then enterprise minister Jonathan Bell.

He said it had to be closed "in view of the significant financial risk" to Northern Ireland's budget "for the next 20 years".

The funding for the RHI scheme was intended - within reason - to come from the Treasury, but it said any overspend would have to be covered by Northern Ireland's block grant from Westminster.

Stormont officials told a Northern Ireland Assembly committee that £30m would have to come out of the block grant to cover the 20-year scheme in 2016-17 alone.

New applications were halted as officials came to terms with the scale of the scheme's overspend.

How did the Northern Ireland scheme differ from its equivalent in Great Britain?

While the RHI scheme in Northern Ireland shared similarities with the one in Great Britain, controls to limit its cost were not copied.

In Great Britain, the subsidy on offer was significantly reduced after the heating equipment had been used for 15% of the hours in a year, preventing a burn-to-earn abuse of the scheme.

That system did not exist in Northern Ireland, where a single, overgenerous, flat-rate subsidy was guaranteed for 20 years.

The Great Britain scheme also had a measure - known as digression - that allowed the tariff to be lowered in response to increased demand, keeping the initiative's budget on course.

Without that, the cost of the Northern Ireland scheme quickly spiralled out of control during the spike in applications in autumn 2015.

The most recent estimate of the scheme's overspend was put at £700m

How many people joined the scheme?

A total of 1,946 applications to the RHI scheme were successful - a 98% approval rate.

The assembly's Public Accounts Committee was told that an independent audit had found issues at half of the 300 installations that had been inspected.

Of those, 14 fell into the most serious category where fraud was suspected and payments to five of those were suspended.

Why is the scheme still costing money?

Successful applicants to the RHI scheme are continuing to receive payments because they agreed contracts with Deti for the 20-year lifetime of the scheme.

As a result, more than £1bn of public money is due to be paid out to claimants over the next two decades.

About £600m of that will come from the Treasury, but the shortfall will have to be paid out of Northern Ireland's block grant.

The most recent estimate of the overspend - revealed in autumn 2017 - was put at £700m.

In April 2017, the then economy minister Simon Hamilton put rules in place that cut the payments that claimants were receiving, with the aim of reducing the scheme's overspend.

That was opposed by a group of the scheme's beneficiaries, and it is challenging the decision in court.

Arlene Foster said she had "nothing to hide" over her role in the scheme

Why did the scheme have such major political ramifications?

A primary reason for the collapse of the Northern Ireland Executive in January 2017 was the RHI scheme.

Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Arlene Foster was Stormont's enterprise minister when the flawed scheme was set up.

When the scale of the scandal emerged in December 2016, political rivals blamed her and called for her to resign.

It was alleged by Mr Bell - Mrs Foster's party colleague and successor as enterprise minister - that DUP advisers had prevented him from closing the scheme when its costs were rising rapidly, a claim that they denied.

Mrs Foster said she had nothing to hide and refused to step aside.

The then deputy first minister - Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness - resigned over the DUP's handling of the scandal, triggering the collapse of the Stormont institutions.

Approaching a year on from that, Northern Ireland remains without a devolved administration.

Retired judge Sir Patrick Coghlin is leading the public inquiry into the scandal

Why was a public inquiry into the scheme set up?

As politicians and the public asked for answers to the scandal in January 2017, the then finance minister Máirtín Ó Muilleoir set up a judge-led inquiry to look at the scheme.

He appointed Sir Patrick Coghlin, a retired Court of Appeal judge, to chair it.

The inquiry will try to establish why the Northern Ireland scheme did not contain the same cost controls as the one in Great Britain.

It will also look at that spike in applications in autumn 2015, and will investigate allegations that the cuts to the scheme's tariff that were being planned at that time were leaked to businesses.

The inquiry will also investigate whether DUP advisers interfered to delay the introduction of cost controls in the scheme - an allegation that they reject.

The inquiry's legal team has already gathered more than a million pages of documentation and public evidence hearings began in November.

A report is not expected until well into 2018.

- Published23 October 2019