Arlene Foster: From trailblazing leader to party civil war

- Published

Arlene Foster on the steps of Stormont on 11 January 2016, on her first day as first minister of Northern Ireland

Arlene Foster faced unprecedented challenges and monumental political changes during her tenure as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

From Brexit to the Irish Sea border and of course the pandemic, it has been a tough few years for Northern Ireland's first minister, culminating in the revolt that has forced her to step down.

Here BBC News NI charts her career.

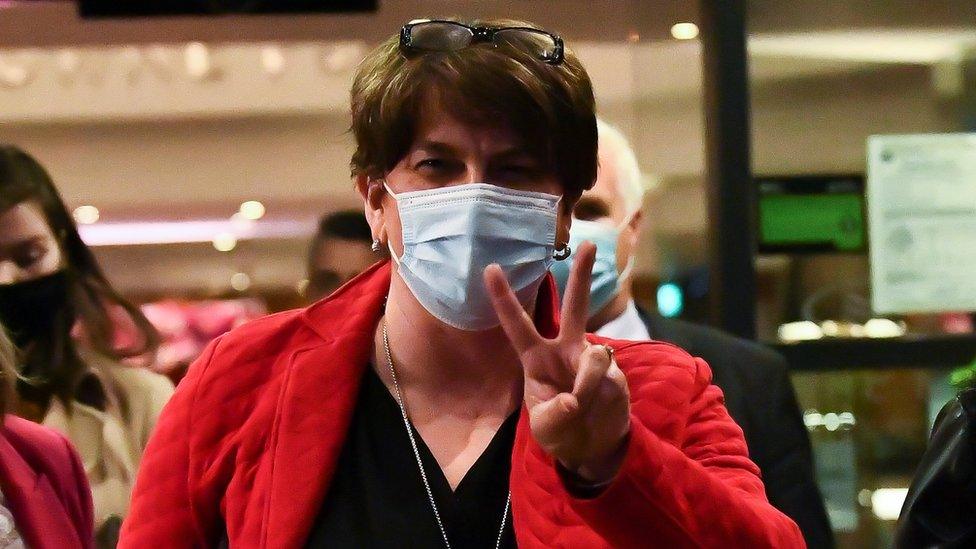

Arlene Foster had to lead NI's response to the pandemic

Who is Arlene Foster?

Mrs Foster, a lawyer from County Fermanagh, held the DUP's top job for just over five years.

She became leader of the party in December 2015 and, the following month as leader of Stormont's largest party, she was appointed first minister of Northern Ireland.

She was the first woman and the youngest person to hold both jobs.

When she took on the roles, she was viewed by many as a capable minister and a popular leader whose personal experiences shaped her passion for the unionist cause.

Arlene Foster was nominated by her predecessor to take the first minister role

Born as Arlene Kelly in 1970, she grew up on a farm in rural County Fermanagh, close to the Irish border.

Gun and bomb attacks

The Troubles played a significant role in her childhood - when she was eight years old, the IRA attempted to kill her father, a reserve police officer, outside her family home.

"My father came in on all fours crawling, with blood coming from his head," Mrs Foster told the Belfast Telegraph in 2015., external

Mr Kelly survived the attack, but the family was forced to sell their farm and move away.

"I now know that this was a deliberate tactic of targeting vulnerable border Protestants to drive them from their homes," she wrote in the News Letter in January 2016, external after taking Stormont's top job.

"I want to send a very direct message to the victims of the violence: I am one of you, I am on your side and I will not let you down."

As as teenager in 1988 the IRA set off a bomb on her school bus and the future first minister was caught up in the blast.

An IRA bomb exploded under Arlene Foster's school bus in 1988

The target of the attack was the bus driver, who was also a part-time soldier in the Army's Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

Arlene Kelly was not hurt in the explosion, but a schoolgirl sitting next to her was seriously injured.

When she left grammar school in Enniskillen, the future Mrs Foster became the first member of her family to go to university, studying law at Queen's University, Belfast.

She became politically active at university, joining the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and chairing Queen's Ulster Unionist Association.

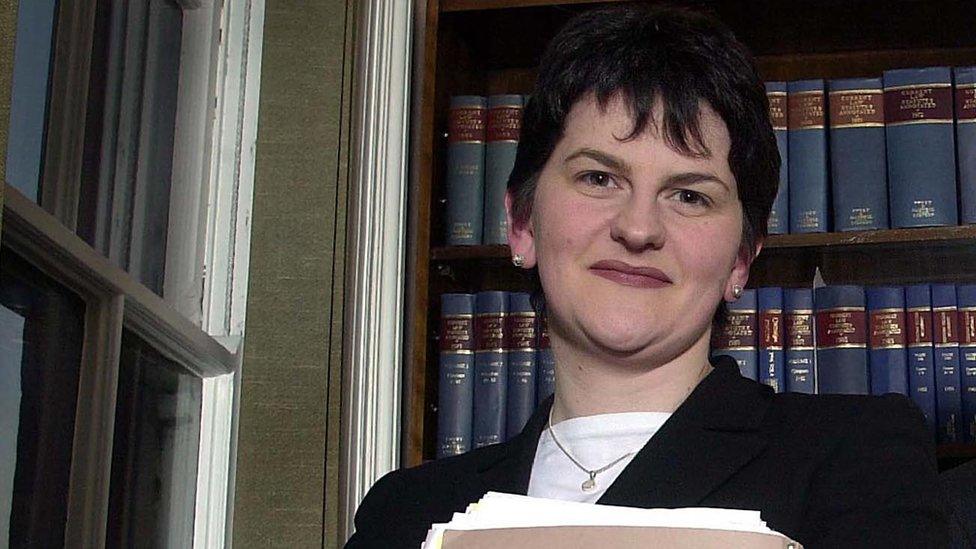

She qualified as a solicitor and began working in private practice in Enniskillen and Portadown, County Armagh.

On 24 August 1995, aged 25, she married Brian Foster, and the couple went on to have three children.

Arlene Foster worked as a solicitor after taking a law degree at Queen's University, Belfast

In 2003, Mrs Foster was elected as a UUP assembly member (MLA) for her home constituency of Fermanagh and South Tyrone.

But she vehemently opposed David Trimble's leadership of the UUP and the following year she defected to Ian Paisley's DUP.

When the DUP entered a power-sharing government with Sinn Féin in 2007, Mrs Foster was given her first government post - environment minister.

She then held posts as minister of enterprise, trade and investment and finance minister.

When former DUP leader Peter Robinson stepped down as first minister in late 2015, Mrs Foster was elected unopposed as his successor.

She passed her first electoral test in May 2016, when the DUP consolidated its position as the largest party in Northern Ireland.

The following month, Mrs Foster and the DUP were on the winning side of the Brexit debate when the UK voted to leave the European Union.

'Cash for ash' scandal

Within a year of taking up her post as DUP leader, she was feeling the heat from a financial controversy at Stormont.

The Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme, which had been set up by Mrs Foster when she was economy minister in 2012, was in danger of a multi-million pound overspend.

The RHI boiler scheme was criticised for 'burn more to earn more' incentives

When she refused to step aside, saying she had done nothing wrong, the then Deputy First Minister Martin McGuiness resigned.

The nature of their joint office meant that when he quit, she lost her job too and a snap assembly election was triggered.

The collapse of Stormont's coalition government in January 2017 would lead to a three-year gap in devolution.

'Absolute disaster'

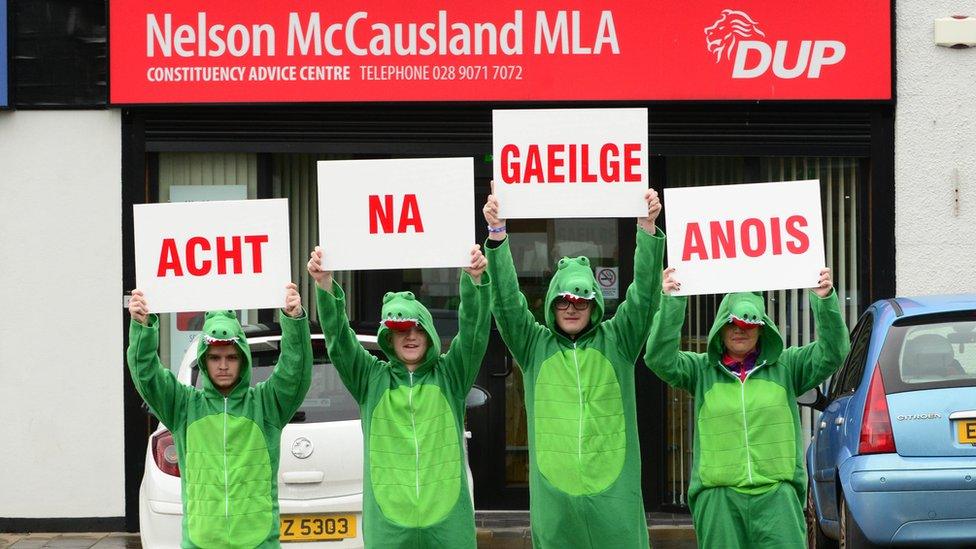

During a bitter election campaign, Mrs Foster compared Sinn Féin to a "crocodile" that would keep coming back for more when she was asked about the party's demand for an Irish language act.

Republicans embraced the crocodile comparison during the election campaign

In the end, the DUP topped the poll and retained its place as Stormont's biggest party, but Sinn Féin narrowed the gap to a single seat.

The result also meant that for the first time, unionists did not hold an overall majority in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

But in June 2017, a snap general election produced a dramatic reversal of fortunes for Mrs Foster.

Prime Minister Theresa May lost the Conservative's majority at Westminster, forcing her to seek the DUP's support to stay in power.

Theresa May's disastrous 2017 snap election thrust DUP leader Arlene Foster into a spotlight rarely enjoyed by Northern Ireland politicians

Mrs Foster and her DUP delegation negotiated more than £1bn in extra public spending for Northern Ireland, in exchange for a confidence-and-supply arrangement with the Tories.

As Mrs May tried to strike a Brexit deal with the EU however, the DUP threatened to pull the plug if it did not agree with the eventual arrangements.

But Mrs Foster argued there could not be an economic border in the Irish Sea, describing that as a "blood-red line" for the DUP.

In November 2018, her party placed its trust in the then backbench MP Boris Johnson who gave the keynote speech at the DUP's annual conference.

Nigel Dodds, Boris Johnson and Arlene Foster at the 2018 DUP party conference

Mr Johnson received rapturous applause when he called for the proposed Irish border arrangements to be junked.

Several months later, now in office as prime minister, Mr Johnson did the complete opposite and agreed to a trade border down the Irish Sea, in order to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland.

Unionists felt betrayed by Mr Johnson - but some pointed the finger at the DUP leadership for allowing its influence to be abused.

Mrs Foster later joked she had sent the prime minister "to the naughty step", with the DUP refusing to uphold its confidence-and-supply commitments with the government.

Boris Johnson 'sent to the naughty step' twice by the DUP, says Arlene Foster

Boris Johnson won a large majority in the December general election that year, and no longer needed DUP support.

The DUP meanwhile lost two of its 10 seats, with its deputy leader Nigel Dodds among the casualties.

Out of influence at Westminster, the party was facing calls from an impatient public to return to power-sharing at Stormont.

In January 2020, devolution was restored with the New Decade, New Approach agreement and the DUP formed a new government with Sinn Féin and three smaller parties.

Mrs Foster resumed her role as first minister and said it was "time for Stormont to move forward".

Mrs Foster, along with Deputy First Minister Michelle O'Neill, was tasked with leading the local response to the biggest global crisis since World War Two.

Michelle O'Neill and Arlene Foster held regular joint press conferences in the early days of the pandemic

The first few months appeared to be marked by a new spirit of cross-party cooperation, as the pair frequently appeared together to appeal to the public to follow strict lockdown regulations.

But by June 2020, political relations were once again at breaking point.

Mrs O'Neill, along with other Sinn Féin politicians, was among about 2,000 mourners at the funeral of senior republican Bobby Storey.

Having ordered so many grieving families to forego the usual funeral customs to protect lives, images of the large cortege caused widespread anger.

Mrs Foster stopped appearing at joint coronavirus press conferences with Ms O'Neill - a stand-off that continued until a second wave of the virus took hold in the autumn.

The Covid crisis was still dominating the news agenda when the new Irish Sea border came into operation on 1 January 2021.

Unionist anger over the Irish Sea border has grown and by April, it was cited among the reasons which contributed to a spate of riots.

A bus was hijacked in west Belfast and left to freewheel along a road before being set on fire on 7 April

Some of Mrs Foster's critics in the DUP were also angered by her decision to abstain in a vote on banning gay conversion therapy in the Northern Ireland Assembly rather than opposing it with the majority of the party's MLAs.

On Tuesday, it emerged that more than 20 MLAs, four MPs and a peer had signed a letter calling for leadership contest.

It was clear that her tumultuous tenure as party leader - and NI First Minister - was coming to an end.

'Glass ceiling'

In her resignation statement, she urged young people to get involved in politics "to shape Northern Ireland for the better".

"My election as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party broke a glass ceiling and I am glad inspired other women to enter politics and spurred them on to take up elected office."

Mrs Foster added: "I have sought to lead the party and Northern Ireland away from division and towards a better path.

"There are people in Northern Ireland with a British identity, others are Irish, others are Northern Irish, others are a mixture of all three and some are new and emerging. We must all learn to be generous to each other, live together and share this wonderful country.

"The future of unionism and Northern Ireland will not be found in division, it will only be found in sharing this place we all are privileged to call home."

'Pretty brutal'

As her party met in a Belfast hotel to ratify the election of her successor Edwin Poots as DUP leader, Mrs Foster shared her thoughts about the nature of her ousting with the BBC's Newscast programme.

Arlene Foster leaving a Belfast hotel the night her successor was officially ratified as DUP leader

"I think I said a couple of days after what had happened that politics is brutal, but even by DUP standards, it was pretty brutal," she said.

"I had absolutely no idea and was telephoned by a close colleague that this was happening on Monday evening and then by Tuesday morning, it was all in the papers, so it wasn't particularly pleasant."

She had originally indicated that she intended to stay on as first minister until the end of June, but Mr Poots was anxious to get his new ministerial team in place sooner.

In the end, it was agreed that Mrs Foster would stay on to host a British-Irish Council summit in her native County Fermanagh on 11 June.

This was her swansong as first minister - her last big political event on her home soil - and it also produced an actual song as Mrs Foster broke into a rendition of a Frank Sinatra classic.

"That's life, that's what all the people say. You're riding high in April, shot down in May," she sang at a press conference.

Arlene Foster does it her way with a Sinatra classic

Her pertinent choice of lyrics meant Mrs Foster bowed out to applause and laughter in Fermanagh.

At midday on Monday 14 June, the assembly member for Fermanagh and South Tyrone addressed the Northern Ireland Assembly for the final time as first minister.

An hour later, her resignation became official.

Over the course of the last few weeks, Mrs Foster has often referred to the end of her "local" political career, so as leaves the stage in Belfast it is unlikely to be her final role in public life.

- Published27 April 2021

- Published13 June 2017

- Published11 January 2016