Martin McGuinness: A life in politics

- Published

Out of the shadows: Martin McGuinness pictured on the Falls Road in 2001

It is a short flick in the dictionary from "paramilitary" to "parliamentary"; it's more of a giant leap in a man's lifetime.

Martin McGuinness, IRA commander turned Northern Ireland deputy first minister, switched from Armalite to an armistice.

When McGuinness triggered the latest political crisis by his resignation at Stormont, the talk on the street was not of the political future.

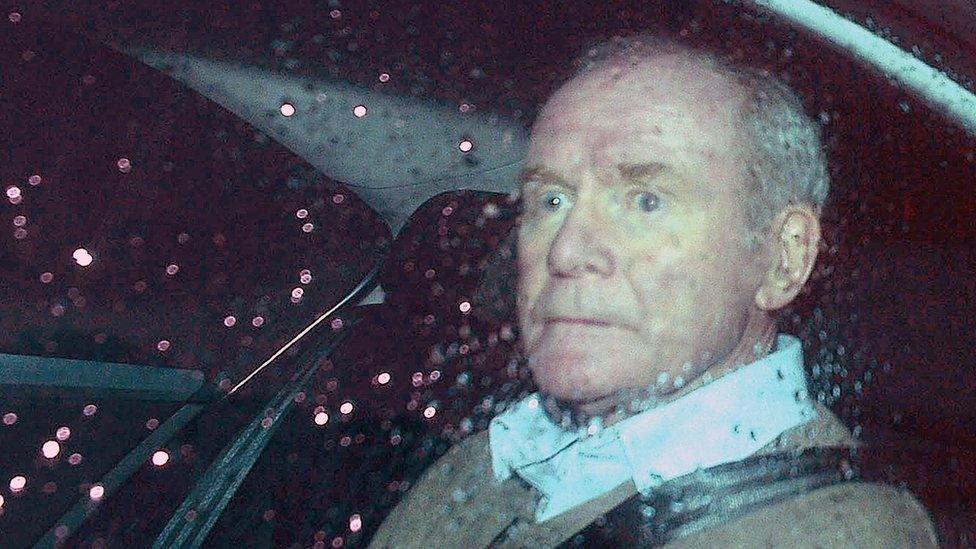

It was that shock picture, snapped through the back window of a rain-stained ministerial car window.

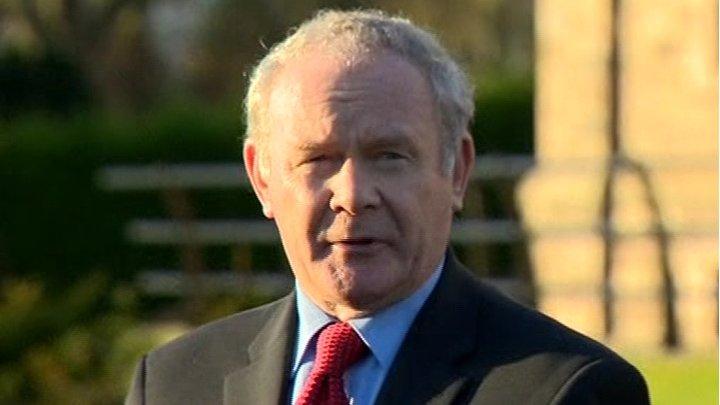

Martin McGuinness' appearance shocked many as he arrived to announced his resignation

It was about how frail and gaunt Northern Ireland's deputy first minister looked. It has been widely reported that he has a rare condition with a specific genetic link to Donegal, external - his past and the history that shaped him.

Martin McGuinness' mother was from Donegal. She moved to Londonderry, where, like generations of women before her, she found work in the shirt factories.

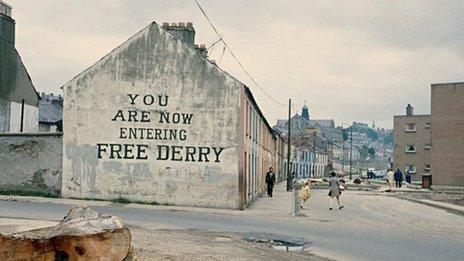

He was one of seven children - six boys and a girl - who grew up in Derry's Bogside in the 1960s.

Times were tough. The Bogside was hopelessly overcrowded as a result of gerrymandering and the poverty of that time. The McGuinness family of nine had two bedrooms, an outside toilet and a scullery - a tiny working kitchen.

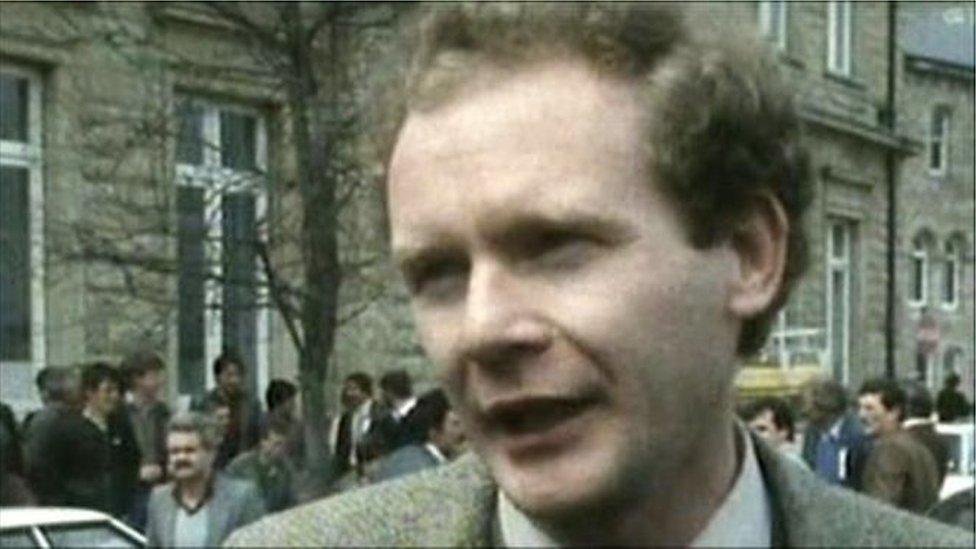

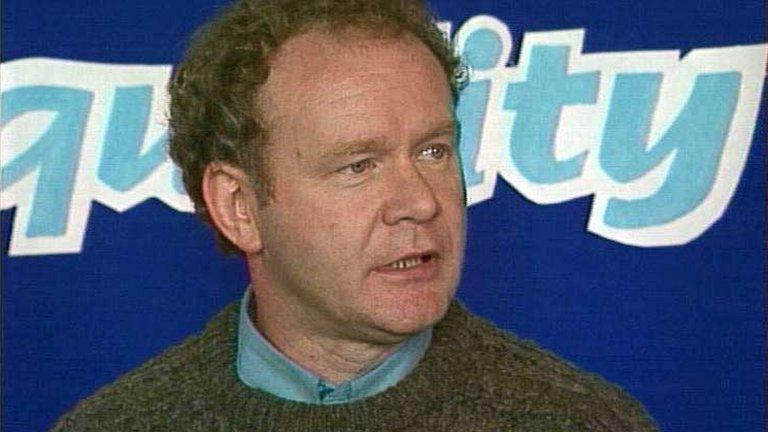

Martin McGuinness says he made the transition to politics in the mid-1970s

In an interview for the Guardian in 2009, external, pressed on why he decided to join the IRA, he talked about how, in 1965, he applied for a job as a mechanic. The interview consisted of three sentences: "What's your name?"; "What school did you go to?" and: "Out the door."

He became a trainee butcher - an occupation ripe for future headline writers.

The young McGuinness was drawn to the civil rights movement, radicalised by discrimination and murder on the streets of his city and caught up in the riots.

He took the violent route. In 1972, at the age of 21, he was second-in-command of the IRA in Derry at the time of Bloody Sunday, when 14 civil rights protesters were killed in the city by soldiers.

Martin McGuinness (left) carries the coffin of IRA man Charles English with his brother William McGuinness (right) at the funeral in Derry 1984

He had a leading role in the IRA during a time when the paramilitary organisation was bombing his home city to bits.

The following year, he was convicted by the Republic of Ireland's Special Criminal Court after being arrested near a car containing explosives and ammunition. He served two prison sentences - he was also convicted for IRA membership.

But he knew how to talk. His leadership potential was spotted early - not just by his own side.

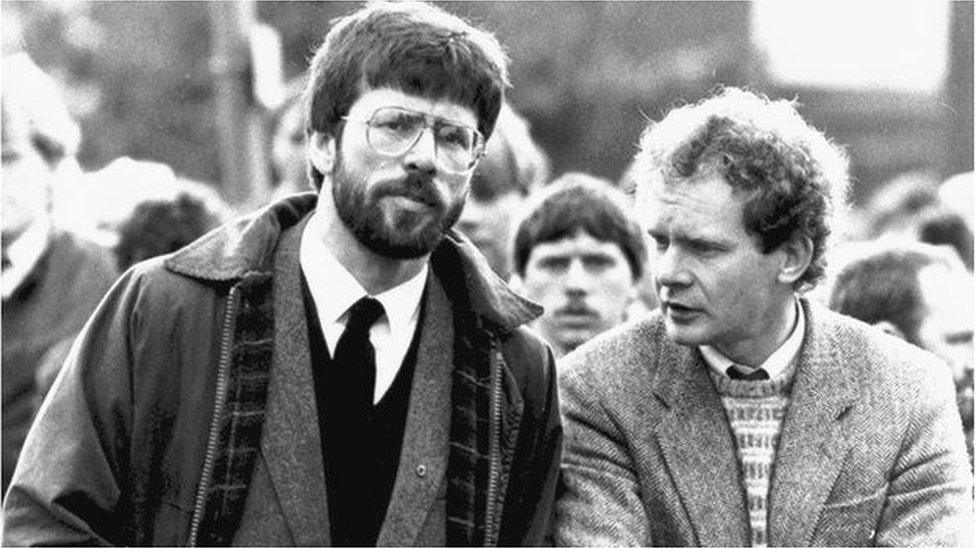

He was 22 when he and Gerry Adams were flown to London for secret talks with the British government: MI5 considered him serious officer material with strategic vision.

He maintained that he left the IRA in 1974 making the transition to politics.

Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams with Martin McGuinness in 1987

"Reports that I am chief of staff of the IRA are untrue. But I regard them as a compliment," he once said.

There were dark years that followed from the IRA hunger strikes to the Brighton bombing, when Margaret Thatcher and the Tory Party conference were targeted, to the 1987 Enniskillen bomb when 11 people died at a Remembrance Day ceremony.

He later said he had no knowledge of the Enniskillen bomb, calling it "absolutely wrong" and he dismissed suggestions that throughout the 1980s he was a leading member of the IRA, a time when the organisation was responsible for hundreds of murders.

In 1993, he was labelled "Britain's number one terrorist" in Central Television's The Cook Report. He called the report "cowardly and dishonest" television.

The shift to the politics of peace came slowly.

In 1986, the party decided to contest elections in the Republic of Ireland. Ten years later, the landscape in Northern Ireland had changed irrevocably. McGuinness was chief negotiator in the peace process.

Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness smile after being sworn in as first and deputy first ministers of the Northern Ireland Assembly

In 1997, he became MP for Mid Ulster.

He took on the post of education minister in the Stormont administration and his legacy was the decision to kill off the 11-Plus examination - a political hot potato that still stokes up a fiery glow in the eyes of those opposed to the move.

By 2007, he was Northern Ireland's deputy first minister standing alongside First Minister Ian Paisley. It was the kind of marriage that only a mad matchmaker contemplates.

The father of the Free Presbyterian Church - the DUP leader famed for "Never! Never! Never!" - and the hardliner republican once wedded to the armed struggle?

Martin McGuinness and Arlene Foster

But there was a click. They became the poster boys for modern politics - the Chuckle Brothers who giggled together.

When a stony-faced Peter Robinson, DUP, stepped into the first minister's shoes, McGuinness said the "honeymoon" was over. The pair was more like the Brothers Grimm.

From rocky beginnings, it proved a slow thaw. When DUP leader Arlene Foster took the reins, it proved frostier again.

A month after she took on the post of first minister in January 2016, she said it was difficult for her because he gave the graveside oration at the funeral of the man who, she believes, tried to kill her father.

The ice thickened and became impenetrable after McGuinness resigned in protest at her refusal to stand aside for an investigation into a botched green scheme that she set up.

Stormont's institutions subsequently collapsed.

Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness met the Queen for the first time in June 2012

Nevertheless, over the past ten years for Martin McGuinness, there were seismic moments.

There was the famous handshake with Queen Elizabeth II; there was a toast to her Majesty at Windsor Castle as the band played God Save The Queen - gestures that stuck in the gullets of hard-line republicans and loyal servants of the Queen alike.

In recent years, he said: "My war is over. My job as a political leader is to prevent that war and I feel very passionate about it."

He did it his way... right up to the moment on Monday 9 January, when he signed off at Stormont, saying the time was right to "call a halt to the DUP's arrogance".

- Published22 June 2012

- Published26 September 2014

- Published27 June 2012