Stormont: All you need to know about NI's latest political crisis

- Published

Arlene Foster and Martin McGuinness, before it all went wrong

A guide to what is behind the current crisis in Northern Ireland's political institutions.

How does Northern Ireland's government work?

Northern Ireland has a power-sharing government, in which Irish nationalists and unionists must work together.

The system was set up to provide a political settlement after years of conflict. A first minister and a deputy first minister are appointed to lead an Executive Committee of Ministers.

In the current Stormont Executive, the Democratic Unionist Party has six ministers and Sinn Féin has five. An independent unionist holds the justice ministry.

Westminster has delegated powers to Stormont which cover most areas of government.

The executive has responsibility for healthcare, education, transport, policing, justice, agriculture, economic matters and many other issues.

The first and deputy first ministers lead the executive. Although they have different titles, they basically have equal authority and cannot work in isolation from each other.

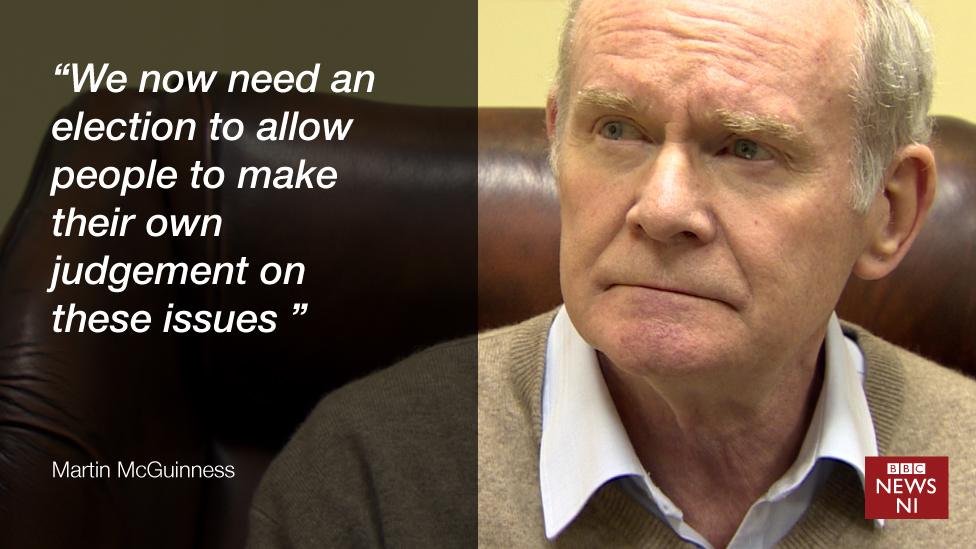

Why did Martin McGuinness step down?

Martin McGuinness resigned as deputy first minister following a row between Sinn Féin and the DUP over a green energy scheme.

The DUP leader, Arlene Foster, was the minister in charge of the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) when it was set up in 2012.

The scheme was designed to encourage businesses to switch from fossil fuels to more environmentally friendly energy sources. But subsidies were overly generous and initially there was no cap on the payments.

The scheme is projected to run £490m over budget, although the DUP say they have a plan to eliminate the overspend.

Mr McGuinness quit after Mrs Foster rejected his calls for her to temporarily stand aside as first minister while an investigation was carried out.

Is it all about the RHI scandal?

The RHI scandal has caused the most public rift between the parties in recent weeks.

But Martin McGuinness referred to other issues in his resignation letter. There are many disagreements between the parties.

On Brexit, the DUP wanted the UK to leave the EU - Sinn Féin took the opposite position.

Sinn Féin wants to legalise same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland, but the DUP does not.

Just before Christmas, a DUP minister withdrew funding for an Irish language bursary scheme, in a move which angered nationalist parties.

There are also differences on the issue of how new agencies to investigate killings from the Troubles should operate.

James Brokenshire is obliged to call a fresh election if there is no resolution by Monday evening

Why is an election likely?

The rules on how Northern Ireland is run were drawn up in previous political agreements.

Martin McGuinness's resignation as deputy first minister automatically put Arlene Foster out of her job as first minister, because they hold a joint office.

After the positions have been vacant for seven days, the administration is effectively dead and the law says the Northern Ireland secretary must call a new election after a "reasonable" time period.

Sinn Féin has made it clear it will not re-nominate anyone to become deputy first minister.

What form will an election take?

Elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly use a form of proportional representation called the Single Transferable Vote (STV).

Voters rank candidates in numerical preference. But the next assembly election will see one significant change from previous ones.

There will be a reduction in assembly members from 108 to 90. Northern Ireland's 18 constituencies will return five MLAs each, not six as was the case beforehand. The number of MLAs has been cut in order to reduce the cost of politics.

MLAs walked out of the Assembly in December in protest just as Arlene Foster started to speak, leaving just the DUP in the chamber.

Who will run Northern Ireland in the mean time?

Although the first and deputy first ministers are out of their office, other ministers remain in place. However, they cannot take any major decisions, as they require the approval of the executive, which will not meet.

Will an election sort out the problems?

It is just eight months since the last NI Assembly election. In the May 2016 poll, the DUP and Sinn Féin were well ahead of their rivals.

After the new election, negotiations will take place between the parties to see if power-sharing can be restored.

If the DUP and Sinn Féin are again returned as the largest parties (as most observers expect), the disagreement between them is so deep that long and complex negotiations are likely to be needed before they are prepared to go into government with each other again.

What form will negotiations take?

After an election, the parties have three weeks to form an executive. If that deadline runs out - then technically, there should be another election - though few expect that would happen, in reality.

The British and Irish governments have said they are ready to help in any process which could restore stability.

A wide range of unresolved issues could be on the table - the workings of the Stormont Assembly and Executive, the operation of new agencies to investigate Troubles' killings, budgets, the Irish language, a Bill of Rights, the status of Northern Ireland after Brexit, minority rights and lots more.

Arlene Foster has repeatedly refused to resign over her role in the RHI scandal

What if there's no agreement?

If a power-sharing government cannot be re-established, then some other way of governing Northern Ireland will have to be found.

The last time devolution was suspended, there was direct rule from Westminster - ministers from the British government took over Stormont departments.

Nationalists are calling for a form of "joint authority", where the British and Irish governments share responsibility for running Northern Ireland. But unionists will be hostile to that idea.

The Northern Ireland Secretary James Brokenshire has said he is not contemplating any alternatives to devolved government.

What difference is this making to life in Northern Ireland?

The political crisis is affecting many areas of life.

A Stormont plan to tackle hospital waiting lists cannot go ahead without an Executive.

The uncertainty over who will be making government decisions in a few weeks' time is causing concern among public sector workers.

And business leaders are worried the instability could affect overseas investment.

There is a question mark over who will speak for Northern Ireland as the UK begins the process of leaving the EU.

While there has been a degree of public indifference to previous crisis situations at Stormont - the impending collapse of the executive is generating lots of talk - and unease.

- Published11 January 2017

- Published7 November 2017