Martin McGuinness: The end of a long journey

- Published

The political retirement of Martin McGuinness on Thursday due to ill health marks the end of a remarkable journey. Perceived by some as a terrorist, others as a freedom fighter, he ended up a statesman, a journey similar to those previously made by other historical figures from Menachem Begin to Jomo Kenyatta and Nelson Mandela.

It also marks the closing of a chapter in Northern Ireland's turbulent history in which Mr McGuinness played a crucial role both as perhaps the most important IRA leader on the island of Ireland and one of its most skilled and charismatic politicians. Without his endeavours, in umbilical political partnership with his former comrade-in- arms, Gerry Adams, I doubt if Northern Ireland, despite the continuing fragility of its institutions, would be where it is today.

I first met Martin McGuinness 45 years ago this month, shortly after the day that became notorious as Bloody Sunday when British paratroops shot dead 13 civil rights marchers in the Bogside enclave of Londonderry/Derry.

I remember watching a candle-lit procession on its way to the church where the coffins of the dead were lying and being told by the nationalist politician, John Hume, to keep an eye on one of the mourners.

He pointed to Martin McGuinness. I followed his advice and soon met him on the steps of the gasworks that served as the IRA's headquarters in the Bogside. At the time he was second in command of the IRA's Derry Brigade. He was soon to become its commander.

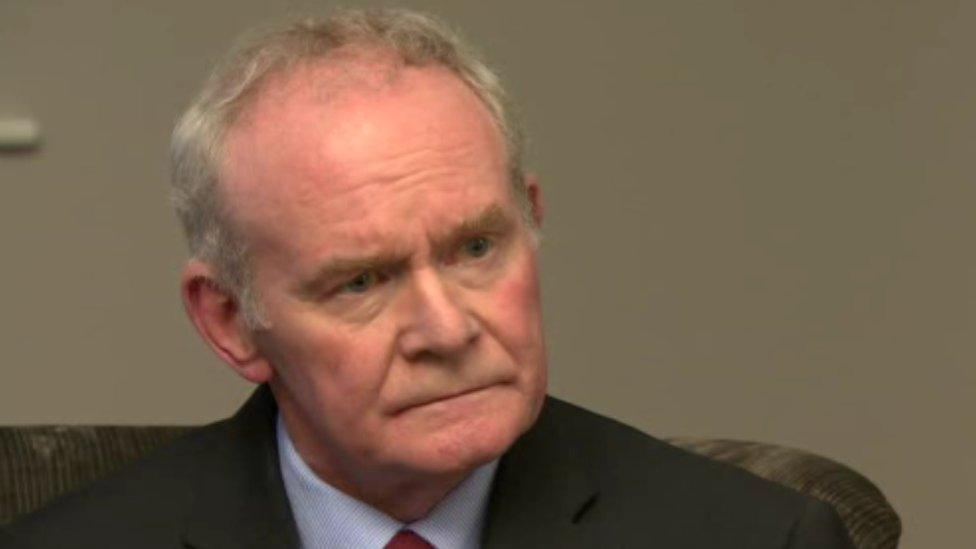

Martin McGuinness with Gerry Adams, 1987

He did not fit the stereotypical role of an IRA commander at the time. He was personable, highly articulate and utterly committed to his cause of getting the "Brits" out of the North.

A few months later, following an IRA ceasefire, he was sitting down in a posh house in Chelsea, along with Gerry Adams, as part of the IRA delegation that met the Northern Ireland Secretary, Willie Whitelaw. The IRA said it wanted a British withdrawal by 1975. Not surprisingly, the talks got nowhere and it was back to the "war".

If anyone had looked into a crystal ball at that time and told me that the young IRA commander would go on to become Northern Ireland's deputy prime minister, sharing power and joking, as "the chuckle brothers" with his former arch enemy, Ian Paisley, and then would don white tie and tails to dine with the Queen at Windsor Castle, I would have said that pigs might fly. But pigs did.

"The chuckle brothers" - Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness at the Northern Ireland Assembly, 2007

Mr McGuinness's role was critical in persuading the IRA's rank-and-file that "armed struggle" had run its course and the future road to Sinn Fein's holy grail of a united Ireland lay in sharing power at Stormont with its unionist opponents.

This was tantamount to accepting partition (the division of Ireland in 1922 into two states) and the role of the British state - albeit, as far as Sinn Fein is concerned, a temporary accommodation as a means to an end.

Remarkably Mr Adams and Mr McGuinness finally persuaded the majority of the IRA to swallow the political heresy and agree to the ceasefire of 1994 that was to lead on to the Good Friday Agreement four years later.

A measure of the faith and trust that rank-and-file IRA men and women had in Martin McGuinness is reflected in the sentiment I heard from many of them that "if it's good enough for Martin, it's good enough for us". Such sentiments speak volumes of Mr McGuinness and the esteem in which he was held as IRA leader.

These landmark steps were only made possible as a result of a protracted and fraught secret back-channel dialogue, via an intermediary, between MI6 and MI5 in which Mr McGuinness was the key conduit to the IRA's ruling Army Council.

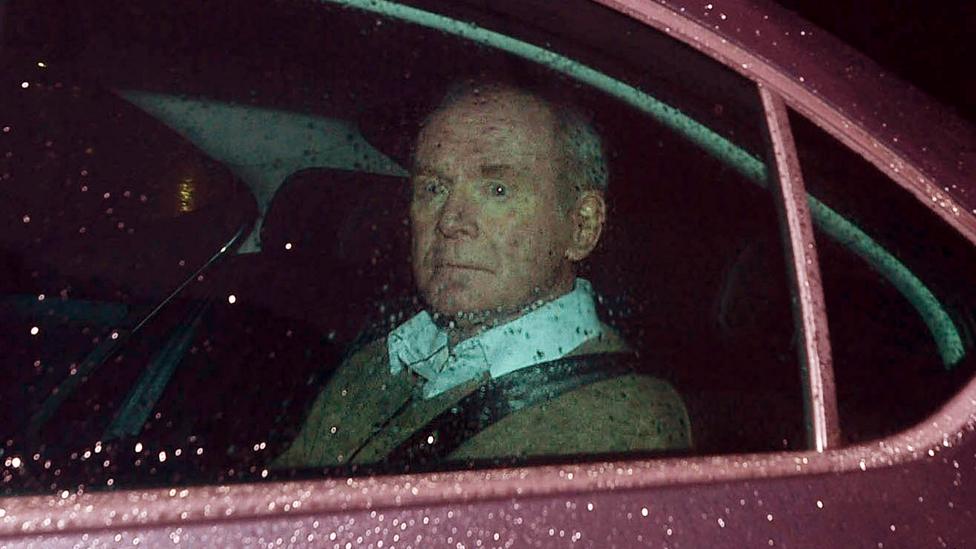

Martin McGuinness leaves Stormont after resigning earlier this month

But Mr McGuinness, because of his IRA past, remains a controversial figure. There are still some Unionists who would take issue with the tribute paid by Ian Paisley's son who said that by working with his father, Martin McGuinness had "saved lives" and "made countless lives better".

His critics can only see him as the former leader of a terrorist organisation responsible for a grievous toll of death and destruction. They will never forget - or forgive the IRA - for the lives of the hundreds of policemen, soldiers and civilians murdered in the IRA's campaign and the number of families who have been left bereft.

But for me, the true recognition of the journey Mr McGuinness has made came in an interview I did with the mother of Marie Wilson, the young woman who died in the IRA's bomb attack on the Remembrance Day parade in Enniskillen in 1987.

The intelligence services believe that Martin McGuinness, although he denies it, was at that time the acting head of the IRA's Northern Command that prosecuted the "war" in the North.

In words of moving candour, Mrs Wilson said she respected Mr McGuinness's role in helping to bring the conflict to end and making such attacks, she hoped, a thing of the past.

- Published19 January 2017

- Published20 January 2017