Walking with Martin McGuinness and Buttons the dog

- Published

The panoramic view from Grianan of Aileach - a special place for Martin McGuinness

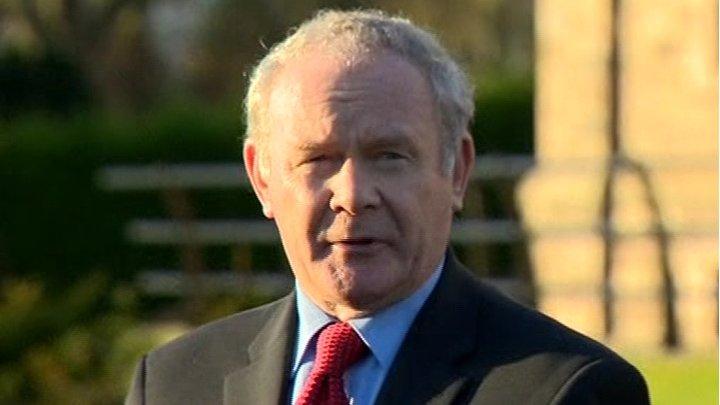

Buffeted by a freezing wind on a chilly afternoon last April, I accompanied Martin McGuinness and his dog for a stroll around an ancient Irish hill fort just across the border on the Inishowen peninsula in Donegal.

Grianan of Aileach, external was a special place for the deputy first minister, perhaps because it reminded him of Ireland's ancient history, but also because it afforded panoramic views across the counties of Donegal, Derry and Tyrone.

He could look down on the green fields and the waters where he spent hours fishing for sea trout.

"I am as fit as a fiddle," he assured me as I questioned him over whether he would serve a full term, pointing out that he would be 70 by the time the forthcoming Stormont term was due to end.

He joked that when we had walked up to the summit together he had been in perfect shape, whereas I had been absolutely exhausted.

It wasn't exactly true, but it was good knockabout stuff which served to deflect the question.

If he was thinking about retiring at some point (much later, he told me he had May 2017 in mind), he was determined, at that stage, to keep the matter to himself.

Certainly, I got no sense he was aware of the illness which gripped him later in 2016.

As ever with Martin McGuinness, our encounter worked on several layers.

Devoted to his dog

On one level I was strolling with an engaging companion, devoted to his dog, talking in an animated way about his children and grandchildren.

On the other, whilst he pointed down to the places where he went fishing, I thought back to what had also happened in the countryside before us.

The misty cloud obscured part of the view, but not far down there was Coshquin, the place where the army used to have a permanent checkpoint.

A quarter of a century earlier, the IRA sent army chef Patsy Gillespie to his death at Coshquin, holding his family hostage while he was forced to drive the car bomb which killed him and five soldiers.

'Are there secrets?'

The deputy first minister and I took shelter from the wind inside the hill fort, walking in a series of circles for the benefit of my cameraman.

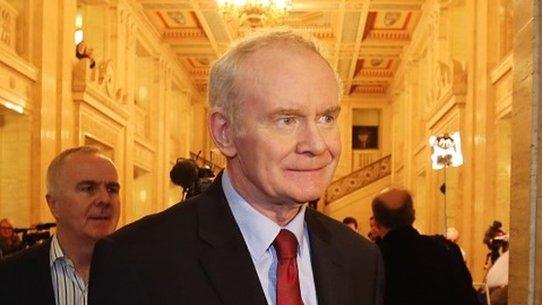

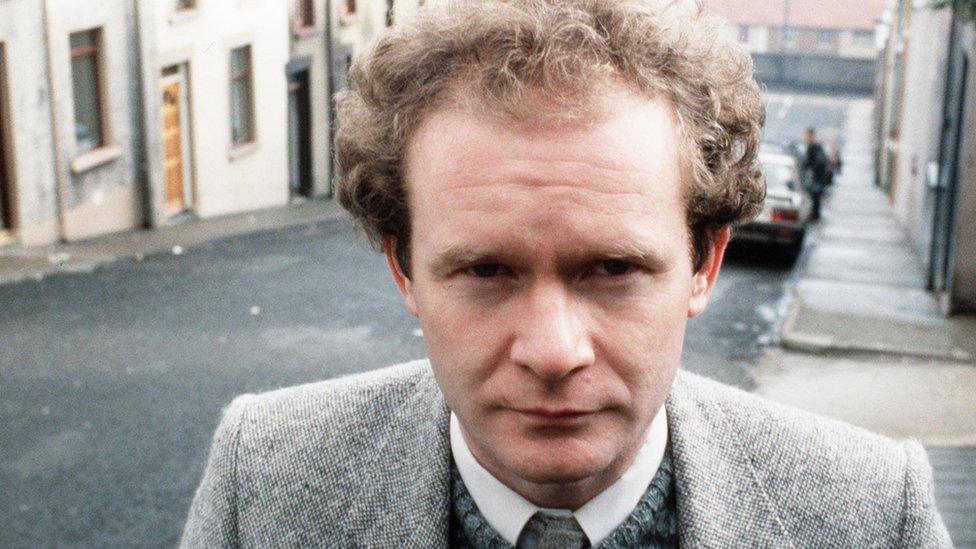

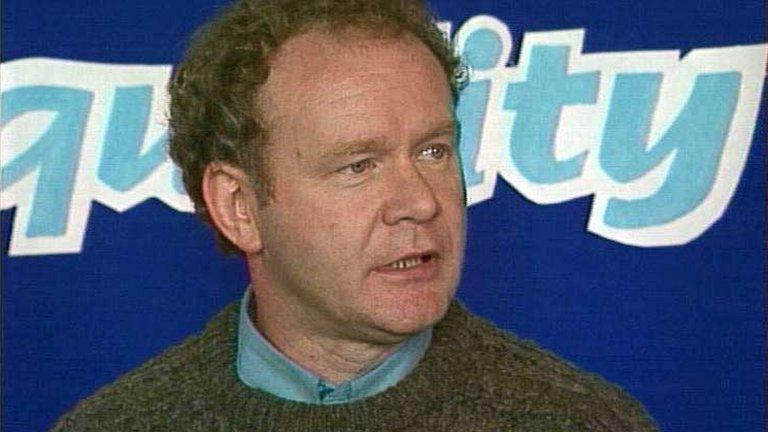

Martin McGuinness, from paramilitary to politician

Amid the cold stone, my thoughts became more sombre.

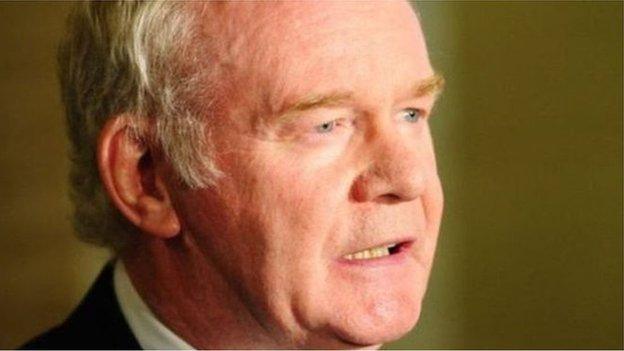

It was a matter of record that my companion was a senior IRA commander, so I asked him: "Are there secrets, that you will take to your grave?"

Not surprisingly he didn't see this as a moment for any personal confessions.

Instead, he talked about the unfinished efforts underway to try to create new bodies which might enable victims of Northern Ireland's troubles to find the truth.

'May never be uncovered'

If those structures were put in place, he added, he would do everything in his power to assist them, including turning up in person to give evidence.

We know now that will never happen, and that many of those secrets may never be uncovered.

Our walk ended on a lighter note, as I put a question BBC Newsline had thrown at all our local party leaders about which football team they would support at the 2016 European championships.

No surprises for guessing Sinn Féin's chief negotiator was a Republic of Ireland fan.

However when our camera clicked off he confided that, although he did not want it reported at that point, he was trying to persuade the DUP leader Arlene Foster to accompany him to both a Northern Ireland and a Republic of Ireland match.

North-south

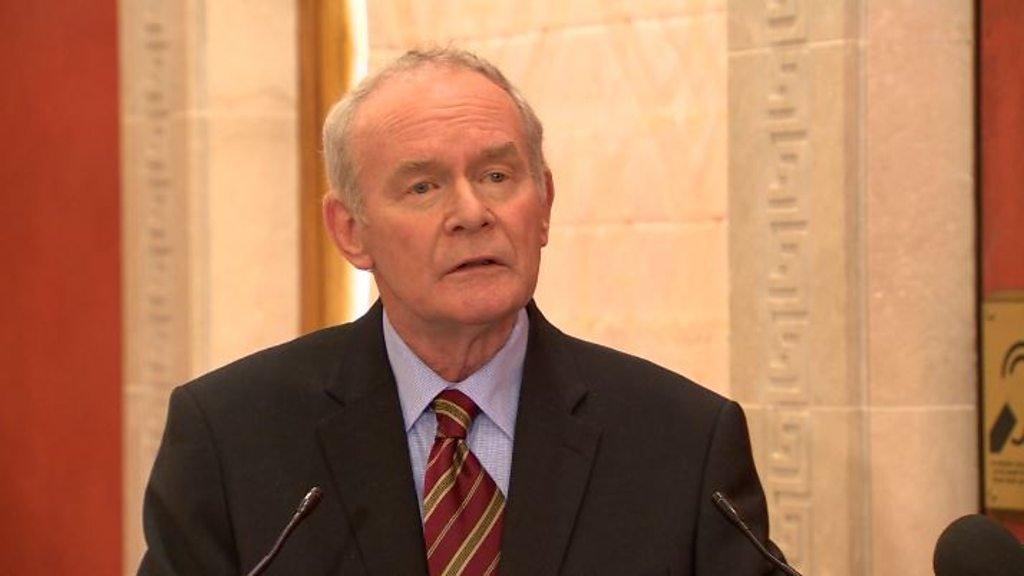

The Queen shook hands with Martin McGuinness in 2012

He believed this would serve as another gesture of improved north-south cooperation.

The DUP's subsequent refusal to take up his offer caused him considerable frustration which he expressed in a final interview I conducted with him in January.

Between the biting wind, with the dog running around, and the need to finish filming our piece before we lost the fading light, I probably didn't pay as much attention to Martin McGuinness's exact words as l normally would.

But when I asked him about the importance of personality as opposed to policy in politics, he gave me a brief self portrait.

He described himself as "a steadying influence" within the power-sharing executive, someone who did not knee jerk, was not reactionary, but was "contemplative" about the challenges and problems Stormont would face.

In recent days, other politicians, such as Peter Robinson and David Trimble, have pondered the impact the loss of Martin McGuinness' "steadying influence" might have had on stoking the current crisis at Stormont.

The debate about where terror ends and peacemaking begins will rage on.

But in the uncertain future we face, Stormont will undoubtedly have need of leaders capable of taking a contemplative view as they survey the political terrain around them.

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published20 January 2017

- Published7 March 2017

- Published27 June 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published26 September 2014