Stormont in limbo after "worst" talks - but what next?

- Published

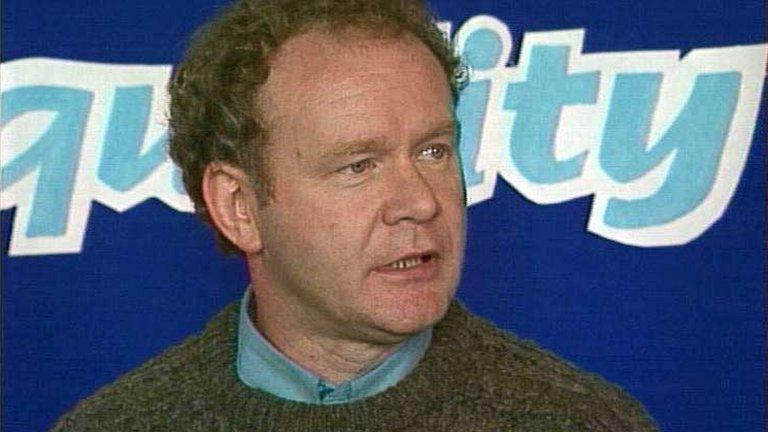

Sinn Féin and the DUP have pointed the finger at each other over the failed talks process

The Ulster Unionist chief negotiator said it was "simply the worst" talks process ever. And there's not a lot of people rushing to contradict him.

Blame will be thrown in different directions.

Sinn Féin said that the DUP should have broken their no-talks-on-Sundays rule. John O'Dowd said he didn't want to impose on any individual's beliefs, but that the DUP should have had a team at Sunday's talks.

The DUP said Sinn Féin shouldn't have wasted time on other days, and should have given the green light for full round-table sessions.

Did Sinn Féin stay away from such round tables because they were effectively rejecting Secretary of State James Brokenshire as an impartial chair?

Sources have claimed that the DUP suggested a wider Culture or Language Act instead of an Irish Language Act

The party said it was more because not enough progress had been made on any issue to justify such a session.

Nevertheless, it's true that republicans were keen to be seen to be doing battle not just with the DUP but also with the British government.

Several sources have claimed that the DUP suggested a wider Culture or Language Act, which would have covered not just Irish but Ulster Scots as well.

This would have saved Arlene Foster any blushes over her "not on my watch" approach to a bespoke Irish Language Act. The DUP won't confirm this, but if the idea was floated it didn't prove sufficient for either nationalists or the Alliance Party.

The log jam over what information might be withheld on "national security" grounds from a new Historical Investigations Unit remained unresolved.

Sinn Féin said on Sunday that the talks process had "run its course"

The prominence Sinn Féin attached to Brexit in its statement calling an end to this phase of the talks indicates the whole question of special status for Northern Ireland might figure in any future negotiations.

What will the Secretary of State do now? It seems likely he may play for time, using previous case law which allows him to take a reasonable period of time before calling an election.

Some sources suggest Westminster might legislate directly in vital matters such as the budget or a rates bill.

However, in the short term, the administration of Northern Ireland looks set to fall to the civil servants operating under tight rules, which initially restrict them to 75% of normal spending limits.

Eventually if no compromise can be found, James Brokenshire will have to decide whether to opt for another £5 million election or bringing back suspension and direct rule - a power taken off the statute book a decade ago.

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published20 January 2017

- Published7 March 2017

- Published27 June 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published26 September 2014