Polio survivor group talks of legacy and a new battle

- Published

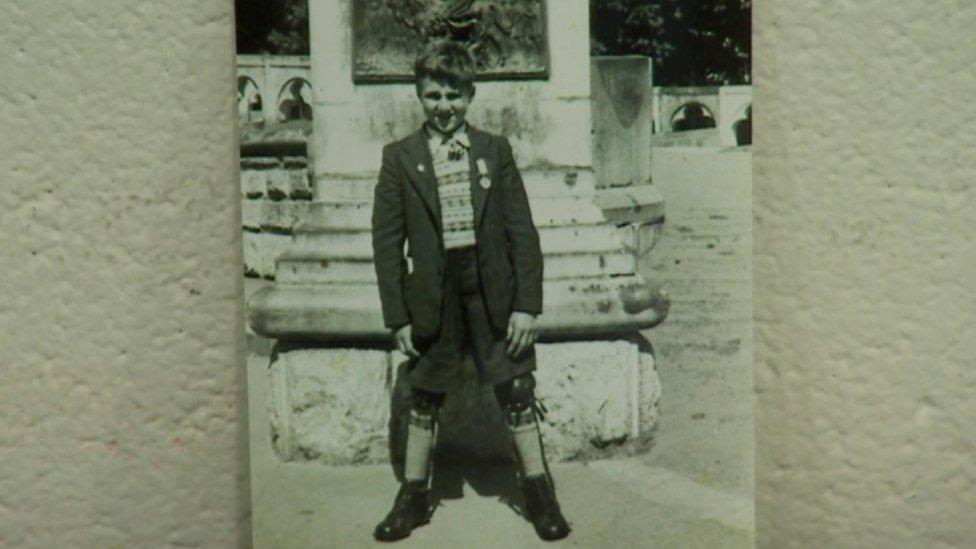

Bobby Doherty was in hospital for a year after contracting polio

At six-years-old, Bobby Doherty from Belfast wasn't playing or riding his bike - he was lying entombed in plaster from head-to-foot in Musgrave Park Hospital after contracting polio.

More than half a century after the infection first struck, he and a group of fellow polio survivors still meet up each week in the Short Strand Recreation Centre.

They play games, reminisce over a cup of tea and support each other in coping with the effects of a disease, which many people think doesn't exist anymore.

Now in his 70s, Mr Doherty still vividly recalls falling ill.

Mr Doherty still uses leg braces to get about

"It was September 1949, a lovely sunny Friday evening and I remember my father taking me to the GP but when we got there the surgery was closed," he said.

"The doctor turned up at my house on Monday morning, tickled my left foot and said 'I'll be back in an hour with an ambulance or a consultant.'

"An hour later I was in an ambulance heading to the Purdysburn Fever Hospital."

'Fear of wasps'

Mr Doherty was to remain in hospital for more than a year with the serious viral infection, which causes muscles to shrink, paralysis and in some cases, death.

When he was discharged, polio had left a permanent mark. He was paralysed in both legs and was fitted with leg braces, known then as calipers, which he still uses to get about.

Another long-standing member of the NI Polio Fellowship is Eddie McCrory, who contracted the disease in 1957, aged five, during its largest outbreak in Northern Ireland.

Mr McCrory was completely paralysed at first

For him too, the memories are sharp.

"My father said I would only be in hospital for the night - and I remember falling out with him when I had to stay much longer than that," he said.

"I was in an isolation ward with three others, and my mother and father would come to the window and look in. She would cry and run away.

"I was completely paralysed at first and I remember a wasp coming into the ward. The other children could cover themselves with their sheets but I couldn't.

"It was terrible and I've had a fear of wasps ever since."

Mr McCrory, who is originally from Belfast's Short Strand but now lives in Carryduff, was left with a severe curvature of the spine.

Polio is now all but eradicated in the UK thanks to a highly-effective vaccine introduced in the 1960s.

Polio does still exist worldwide, although polio cases have decreased by more than 99% since 1988, from an estimated more than 350,000 cases to 74 reported cases in 2015.

Only two countries in the world have never stopped transmission of polio - Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The NI Polio Fellowship playing some sport

But for the friends who still gather in east Belfast, the legacy of the disease lives on, not only in their disabilities but in a new battle with what's known as post-polio syndrome.

Mr McCrory explains that while polio was once considered a static disease, it is now thought fresh symptoms can emerge up to 60 years later.

"I have a diagnosis of post-polio syndrome - I can feel tired, really fatigued and then there are aches," he said.

"Not awful aches but in the parts where I didn't ever have polio. I'm very sensitive to cold. My feet and legs are like blocks of ice because the body doesn't respond quickly enough to changes in body temperature."

'Contented life'

He says there's a lack of awareness of the condition - not helped by the fact many polio experts are retired or deceased.

"Young doctors would have no idea," he said. "When I go to see the neurologist and he sends me to the physiotherapist, she'll often bring in her students and say - this is someone who had polio."

Dr Ultan Power, a molecular virology specialist from Queen's University Belfast, says post-polio syndrome is a neurological disease evident in people who had polio.

Dr Ultan Power says no treatments are currently available for post-polio syndrome

"I've asked a few of my colleagues had they heard about post-polio syndrome and they all said no," he said.

"My understanding is it is not well-known because of the virtual eradication of polio in society."

There are no treatments available but some clinical trials are ongoing, he added.

"One involves using antibodies from people who have the polio virus, which is pretty much everybody as we are all vaccinated," he said.

"They take them from healthy individuals and transfuse them into people who are suffering from post-polio syndrome.

"The hope is that it will have an impact on the residual virus, help eliminate it and improve function for individuals - i.e. their ability to walk - and live a generally contented life."

- Published25 September 2015

- Published17 April 2016

- Published18 April 2016