Eleventh night bonfire builders - Build it high

- Published

'Hurka' the chief architect and builder of the Craigyhill bonfire in Larne, County Antrim, takes a break from stacking pallets.

Award-winning photographer Charles McQuillan has had his share of close encounters.

He even brought a camera to his own heart surgery.

He once photographed pop star Prince, got invited to dinner and arrived late. , external

"It is pretty cool to say I was late for a dinner with Prince," he said.

He has snapped a despairing Cristiano Ronaldo - head bowed, little-boy sad - just after Northern Ireland scored.

But his latest photographic commission was a little closer to home, with Northern Ireland's bonfire builders.

Barry from Kells beats a Lambeg drum in front of the Ballycraigy housing estate bonfire in Antrim, County Antrim.

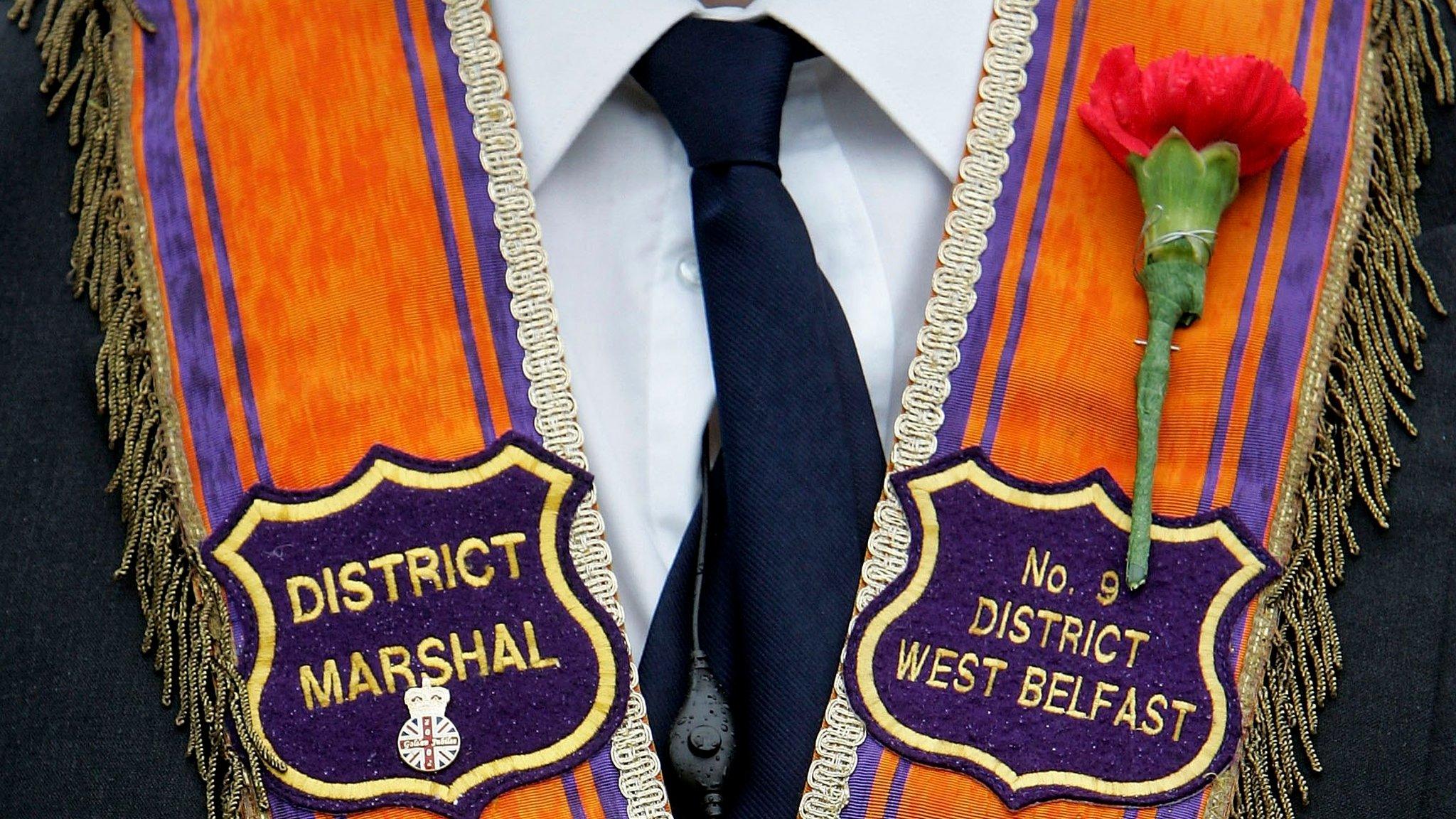

In Northern Ireland, in the run-up to the Twelfth - the centuries old celebration of Protestant King William of Orange's defeat of the Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 - bonfires are a towering deal.

Traditionally, they are lit in many loyalist areas of Northern Ireland on the "Eleventh night" of July.

Culture and controversy - loyalist bonfires in Northern Ireland

Competition for the "biggest and best bony" is rife but so are concerns about safety when huge fires are built close to people's homes.

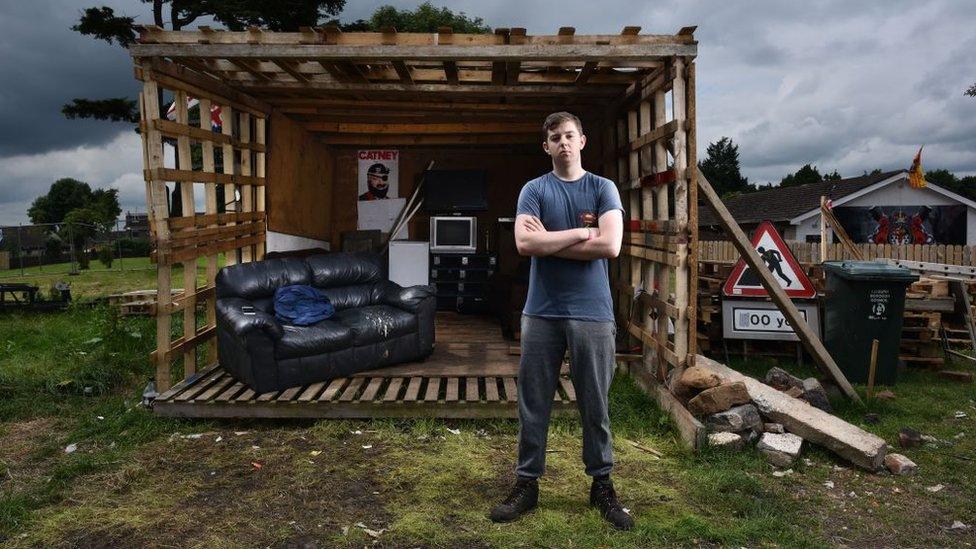

Having finished school for the summer, Tyler Reid helps guard the Lisburn bonfire.

Most pass off without incident, however, some are criticised for health and safety reasons. Four Belfast bonfires are currently the subject of court injunctions. Others are controversial for placing Catholic and Irish symbols onto top of the bonfires for burning.

McQuillan, a photojournalist with more than 30 years' experience, was searching for a different angle for this year's Twelfth.

He pitched the idea of behind-the-scenes portraits of the bonfire builders. His bosses said yes.

Davy McGrotty watches over the unfinished bonfire in an area known as The Village, in south Belfast.

"Then, I just had to go and do it," he joked. "I thought: 'Now I am going to have to walk into a situation that I don't feel is welcoming.'"

But it mattered to him.

"With so many bonfire pictures, you are photographing the structures and how big they are. I wanted to challenge myself and see beyond that. I wanted to portray the people behind them, to make them human."

Stewart McClelland and Winston Wylie proudly display their finished bonfire on the Ballykeel estate in Ballymena, County Antrim.

His mission, stretching over four days, was to visit a total of nine bonfire sites across Northern Ireland and meet the builders intent on making theirs the biggest and the best.

Competition is fierce and watchers are appointed at bonfire sites lest someone sabotages the Eleventh party by setting the huge pyres on fire before the night itself.

Charles McQuillan set out.

Brothers Mark and Hayden watch over the nearly completed bonfire on the Ballyduff estate in Newtownabbey, County Antrim.

Bonfire number one and the builders were wary. The usual questions were asked: "Who are you? Where are you from?"

At one site, in Larne, 15 men were hard at work. It was a challenge to just walk in and ask to take pictures.

"It felt foreign, having to do that," he said.

But with each visit to each bonfire site, the task got easier.

Reece Moore stands guard over the Ballymacash bonfire in his makeshift hut which is manned 24 hours a day in Lisburn, County Antrim.

"I was able to show them what I had done. I showed them my photographs and that I was not trying to stereotype them and so they got on board. It was positive," he said.

The Larne bonfire had the feel of a building site about it.

"I was struck by the craic among them. There was banter, they were working hard. And there is certainly an art to building a bonfire. Those fellas were putting in a shift and working flat out, working harder than I was."

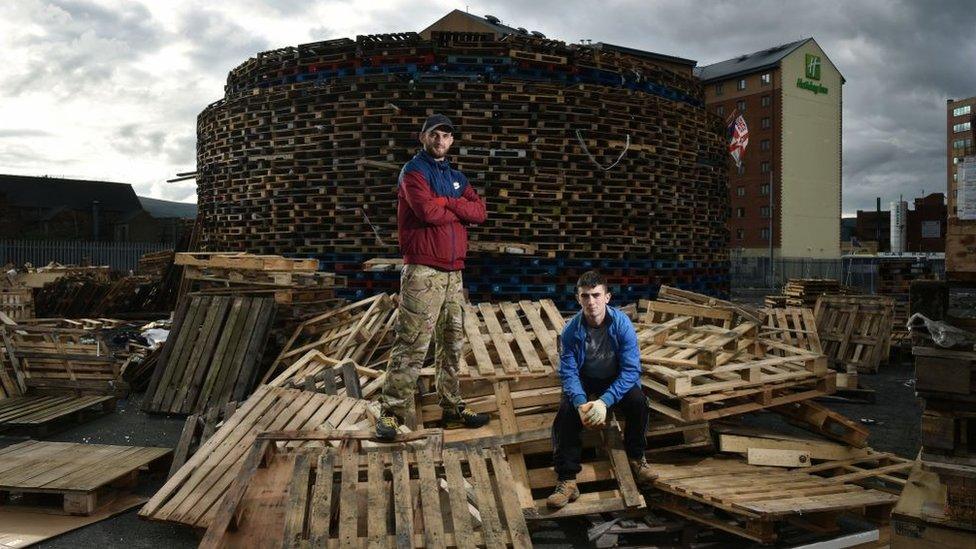

Douglas and Darren McDowell stand with their creation in an unused car park near Belfast City Centre.

At the Antrim bonfire, he struck lucky. A man with a Lambeg drum agreed to be pictured beating it in front of the bonfire. It made for a portrait that spoke about Orange tradition and culture. It said more than a tower of pallets.

And then there was Hurka. He is the chief architect of the Larne bonfire and is photographed, balancing on a ladder, hemmed in by a tower block of wooden pallets.

McQuillan has an eye for what draws others.

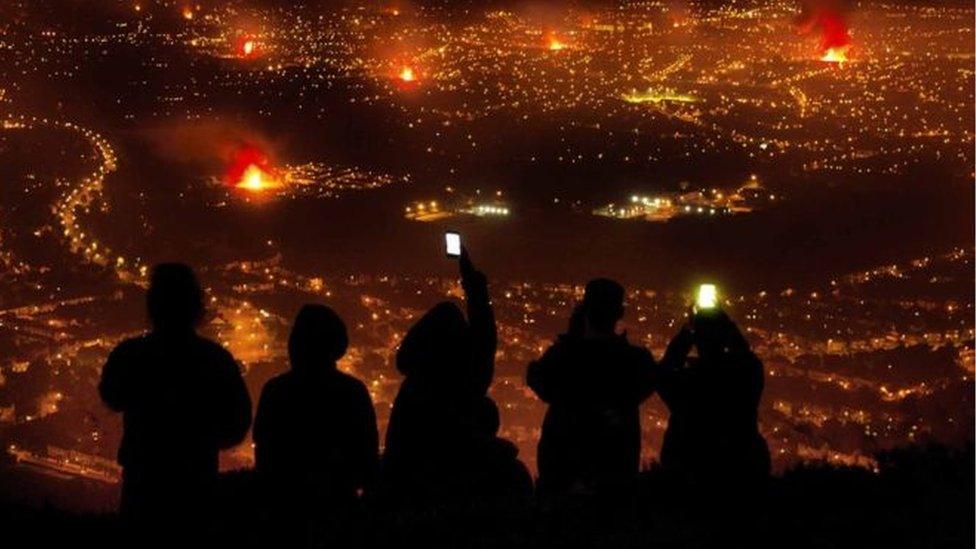

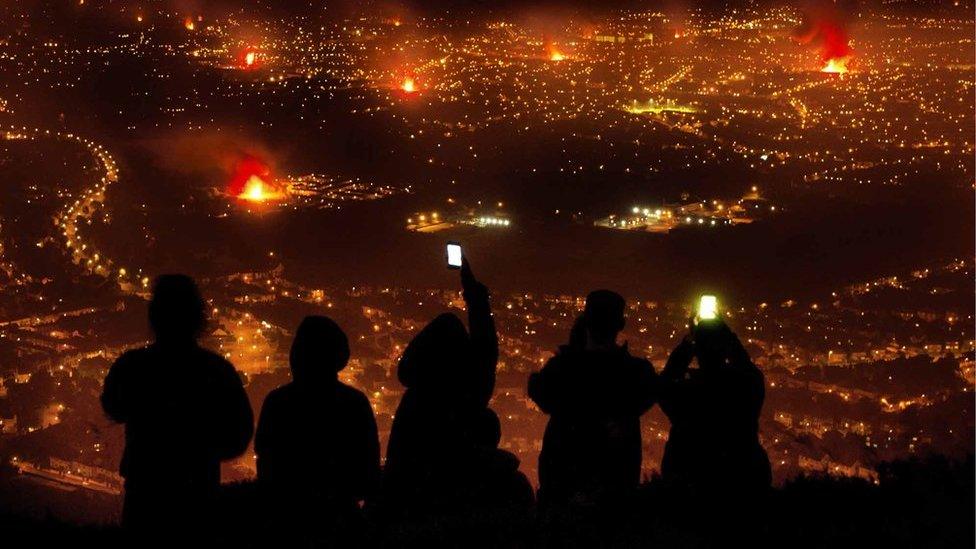

McQuillan took this picture of the Eleventh night bonfires from Cave Hill, Belfast

A unique view of a bonfire in 2015 helped win him the UK Picture Editors' Guild Awards.

"The year before we were flying home from Tenerife on the Eleventh night, just as they were lighting the bonfires in Belfast. I thought, 'There's a great picture, but how would you capture it?'

"I had the idea to take a photo up at Cave Hill, which is one of the highest points overlooking the city. It was a bit of a gamble but it paid off.

"It took the kids there with their smart phones to make the picture - if they hadn't been there, it wouldn't have been the same."

McQuillan took his camera to his own heart surgery

The world of photography has changed dramatically in recent years.

"More and more people have become media savvy, they know that an image can be used against them. It has become more difficult to photograph people on the street. People have become much more wary of the camera," he said.

"But I am not there to hurt anybody."

Behind the lens, he is at one remove from everyone else in the space, but he is also trying to build a connection - and that is what he did with the bonfire builders.

"It is very easy to be dismissive of things we do not understand or approve of. Some of these people do not have a voice and are marginalised. I wanted my photos to be neutral," he said.

He is happy with the response to his latest pictures. Most of all, he said, he wants people to connect.

- Published11 July 2017

- Published10 February 2015

- Published11 July 2017

- Published11 July 2012