Thalidomide mum speaks out on battle

- Published

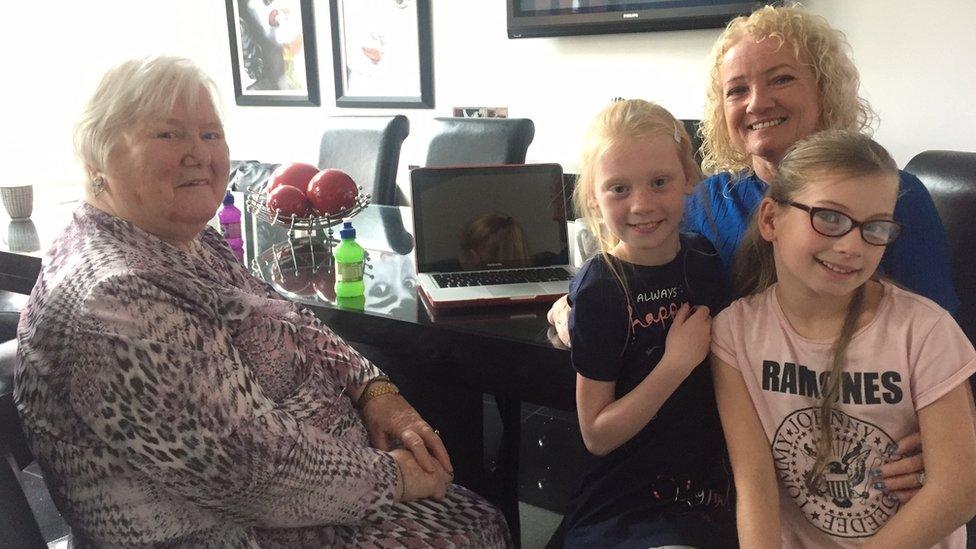

Agnes Lattimer pictured with her daughter Kim Fenton

They say a mother's love for her child is like nothing else in the world.

Kim Fenton, the public face of the Thalidomide campaign in Northern Ireland, knows that only too well.

She and her mum, Agnes Lattimer, share an exceptionally close bond - an ordinary east Belfast mother and daughter with an extraordinary story.

At the heart of it, one of the worst man-made disasters of the 20th Century, the Thalidomide scandal.

Developed in 1954 as a safe sedative by the German pharmaceutical firm, Chemie Gruenenthal, the drug was also used to ease morning sickness.

However, it was banned in 1961 after being linked to severe birth defects and internal organ damage in babies across Europe.

In her first ever in-depth interview, Agnes tells a BBC Radio Ulster documentary why she has ferociously backed her daughter's decades-long fight for truth, justice and compensation for Thalidomide survivors and families across the UK.

It's a battle that's far from over and now being played out in Germany.

Agnes Lattimer has ferociously backed her daughter's decades-long fight for truth, justice and compensation

Now 82, Agnes casts her mind back 56 years to the very day that was to change her life.

Then, she was in hospital and unaware that she was in the early stages of her pregnancy with Kim.

"I was lying awake and this young nurse came around and asked why I wasn't sleeping," she recalls.

"I said that I wasn't tired but she talked me into taking two tablets. I thought nothing of it."

But those two pills were to have catastrophic consequences. Agnes had been given Thalidomide - or Distaval, as the drug was branded in the UK.

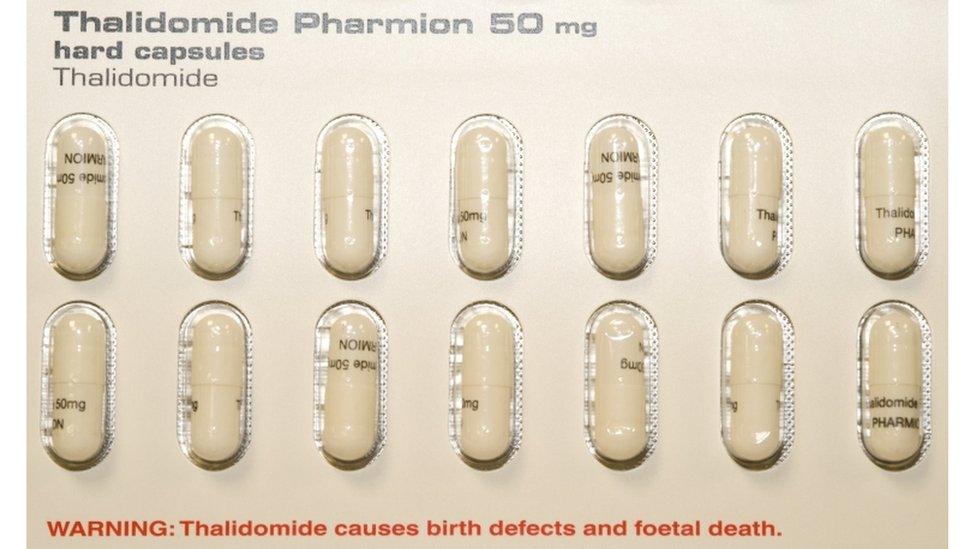

Thalidomide capsules in a blister pack

Unfortunately, Thalidomide's withdrawal came too late for Agnes - Kim was born in June 1962.

"I can remember the doctor saying to me that she had no thumbs... they took me up to the nursery and Kim was lying in the cot. All I saw was her head because they had covered her up in a blanket.

"One of the nurses asked me if I drank much whiskey," says Agnes.

"I said I had never tasted alcohol in my life. They (the medical staff) didn't know what or who to blame so they blamed the mother."

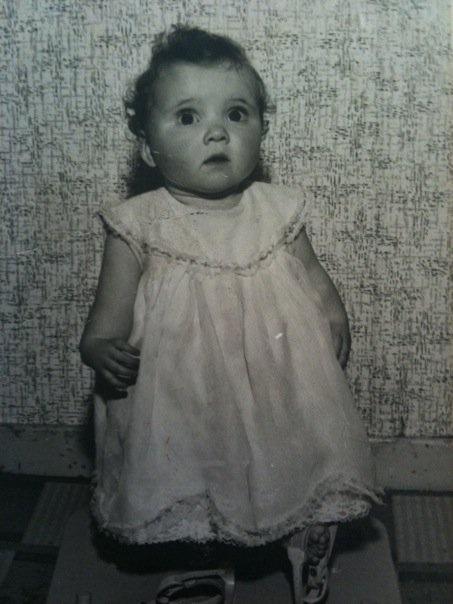

Kim Fenton as a baby

Kim's physical disabilities were severe on the Thalidomide spectrum; she'd also been born with shortened arms and legs, deformed hands, no kneecaps and upside-down feet.

'I felt ashamed'

It wasn't until Agnes brought her home from hospital that she saw for herself the extent of those disabilities.

"I opened up the blankets to change her nappy... and got quite a shock," she says.

"I must have been crying a lot because Kim's father was telling the rest of our children about her. The eldest boy turned around quickly to look at me and from that day he developed a stammer.

"I felt ashamed of myself, that I was so weak not to say to that young nurse (all those months back) that I didn't want those tablets."

Such searing honesty is mirrored by another of Northern Ireland's Thalidomide survivors, Jacqueline Fleming.

Thalidomide survivor Jacqueline Fleming says many mothers carried a lot of guilt

"I do think a lot of the mothers (of Thalidomide babies), to their dying days, felt guilty about it, but it wasn't their fault," she said.

"The doctors didn't know what they were giving them and the mothers didn't know what they were taking," she added.

Longest walk

Now a County Down-based artist, Jacqueline was born with diminished arms and contorted hands. She remembers her own father being treated with insensitivity rather than compassion when she was born.

"Daddy said whenever he arrived at the hospital, he gave the nurse his name and she went: 'Oh that's the armless baby'.

"He later told me that the walk up the hospital stairs was the longest walk of his life."

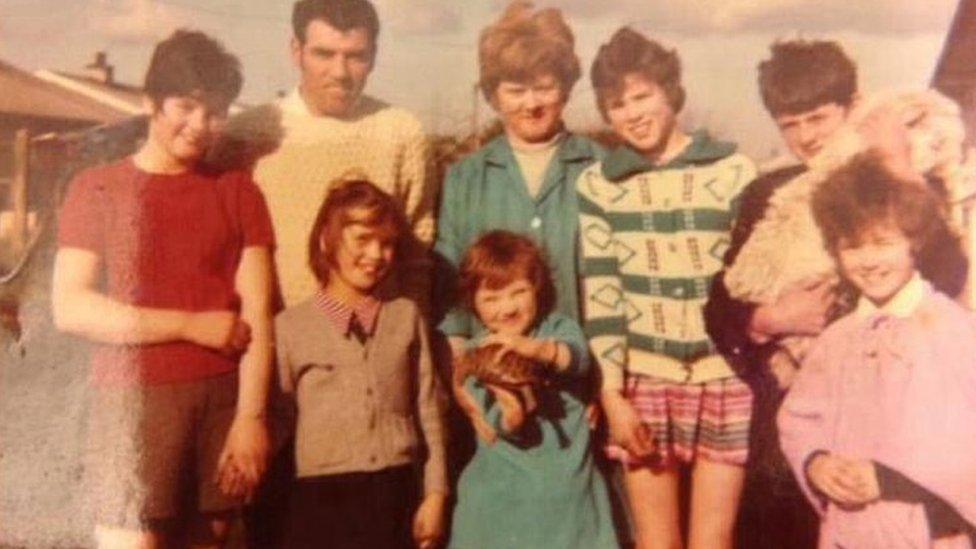

Kim Fenton and Agnes Lattimer (centre) in an old family photograph

Unlike many Thalidomide children, Jacqueline and Kim had normal upbringings.

"I don't know whether it was because I had six older brothers and sisters but I was never bullied or treated differently at school," Kim recalls.

Agnes was never in doubt about educating her daughter in the mainstream school system.

"Her brain was just fine, she wasn't slow, she was normal.

"The principal of (Kim's) primary asked me when she was coming to school. I mentioned her artificial legs and he said: 'Sure, can't she walk'.

"And we've got photos of her on the playground climbing frames with her (artificial) legs on."

German Thalidomide survivor Monica Eisenberg said she supports the British battle against Berlin

Unwavering support at school and from the close-knit community in which the family lived buoyed Agnes over the years.

Government apology

However, she also fought prejudice, recalling a conversation with a local clergyman who would not let Kim attend church because "they didn't have facilities for disabled children".

In January 2010, the British government officially apologised to UK Thalidomide survivors, prompting the Northern Ireland Executive to do the same just a month later and providing more than £1m in compensation.

Those apologies meant more than just words to Agnes.

"I still felt guilty up until that point because no-one had admitted a wrong had been done and said 'sorry'," she says.

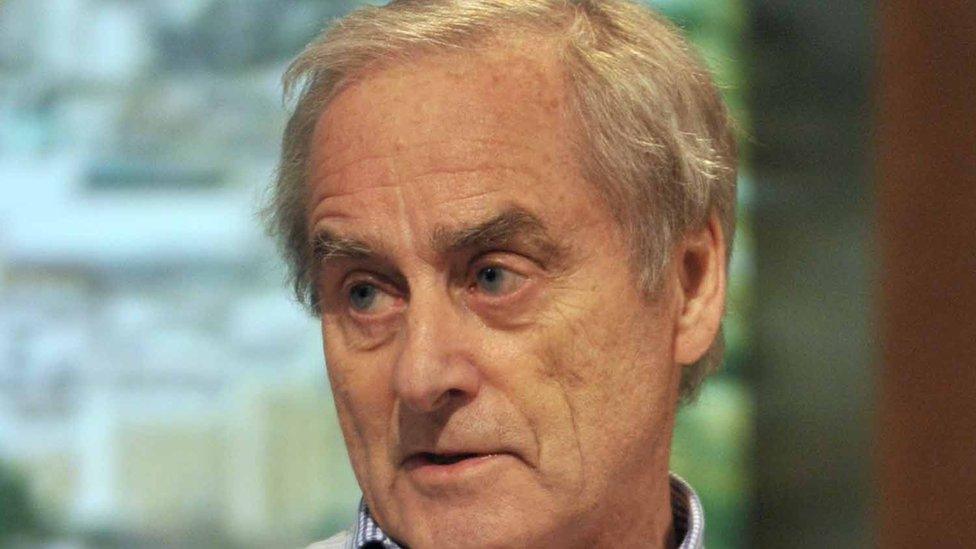

Former Sunday Times newspaper editor Sir Harold Evans

About 2,000 Thalidomide babies were born in the UK and fewer than 500 are alive today - 18 of them in Northern Ireland.

Now in middle age, Thalidomide survivors, like Kim and Jacqueline, say their bodies are starting to fail them and, as their health needs grow, so too does the expense.

That is just one of the reasons why many are looking to Germany where the Thalidomide story began - to gain access to a German government fund that was set up in 1972 to help the country's own Thalidomide survivors.

Agnes Lattimer pictured with her daughter Kim Fenton and Kim's two grand-daughters

From her home in Cologne, German Thalidomide survivor Monica Eisenberg says she supports the British battle against Berlin because "there were no borders for Thalidomide and there should be no borders for compensation".

British Thalidomide survivors also have the support of a former Fleet Street heavyweight Sir Harold Evans.

He and his team of reporters were pivotal in blowing the Thalidomide scandal wide open in the 1960s and 1970s.

"The tenacity (of British Thalidomide survivors) is noble. I can only applaud their actions and do whatever I can to endorse their message," he tells the BBC.

"It is still a very moving thing for me that the people who suffered the most are now trying to relieve the suffering of others."

Thalidomide: The Mother of All Battles airs on BBC Radio Ulster at 12:30 BST on Sunday.

- Published17 January 2016

- Published3 November 2011

- Published7 November 2016