Enniskillen 30 years on: A people together or apart?

- Published

The site where the Enniskillen bomb exploded

Walking through the centre of Enniskillen on a cold, grey November morning is much like walking through any other county town in Northern Ireland.

People are busy out and about getting on with their lives - but this is a place with a dark past.

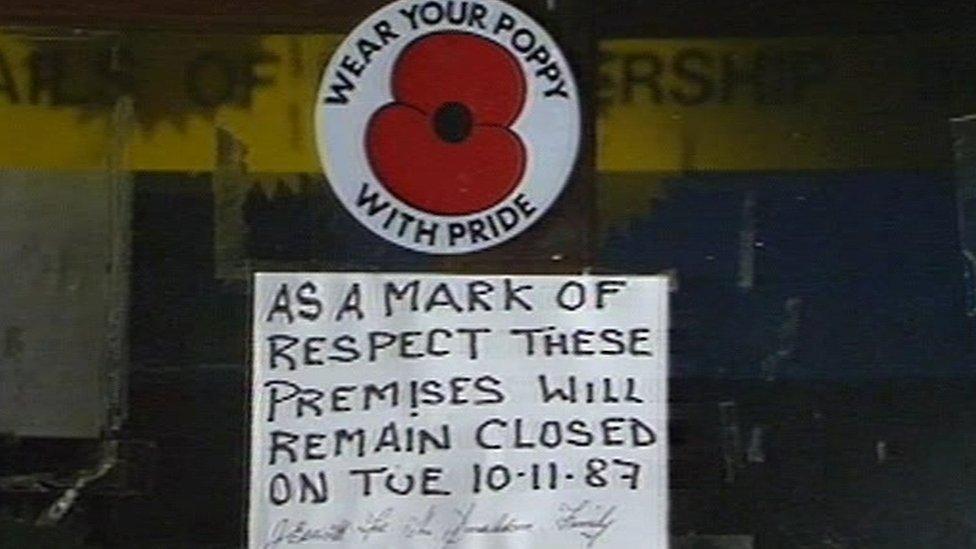

The IRA poppy day bombing 30 years ago blew a large, gaping hole in this community.

The Poppy Day Bomb brought widespread condemnation

In the immediate aftermath, the words and actions of local people helped to keep a lid on an extremely volatile situation.

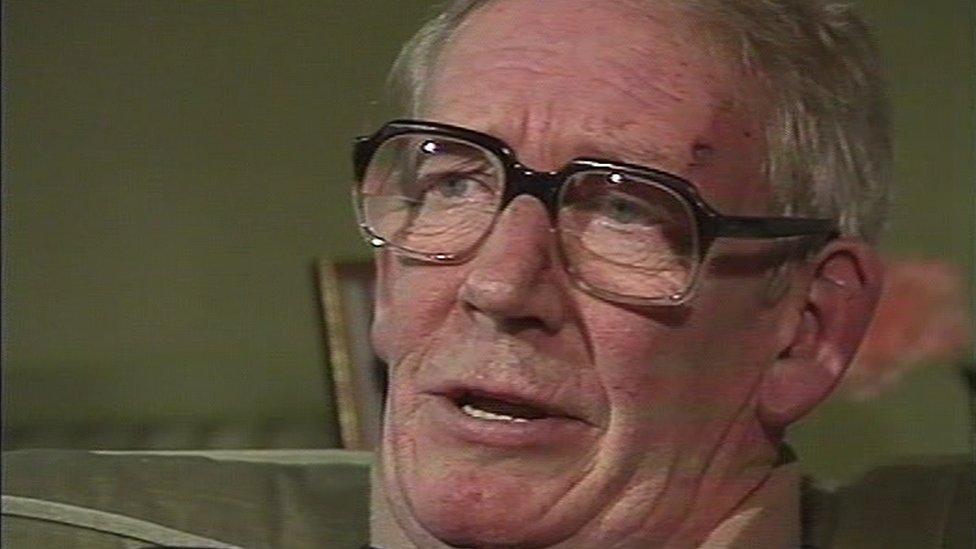

Words such as those spoken by Gordon Wilson that were broadcast around the world.

He said he had prayed for the bombers who had killed his 20-year-old daughter, Marie, in the attack at the cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday in 1987.

Gordon Wilson's daughter was the youngest person to die in the atrocity

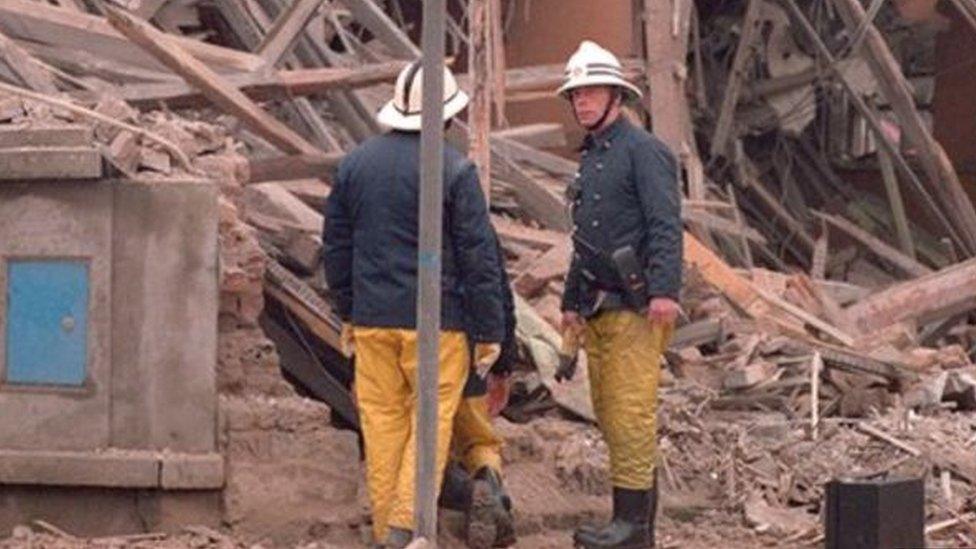

Eleven other people died from injuries inflicted by the blast.

What Gordon Wilson said helped bring about the birth of the Spirit of Enniskillen Trust, set up to foster forgiveness and reconciliation.

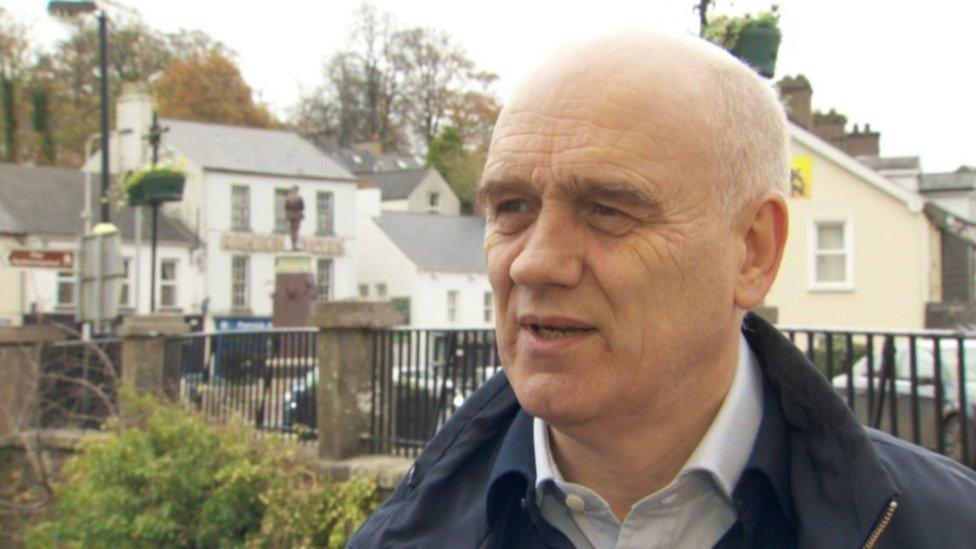

Gerry Burns, who narrowly escaped death as he stood with others awaiting the laying of the poppies that day, was a founding member of the trust.

Gerry Burns was a founding member of the Spirit of Enniskillen Trust

"The intention was to send many of our young people from Fermanagh and across Northern Ireland to other countries around the world where diversity is accepted and respected," he said.

"We did that for hundreds of people who now would be in their late 40s.

"They were sent to the United States, Canada, Mexico and Asia and they reported back on what they found there.

"The idea was later introduced into schools as well and, I believe, out of that came better community relations."

The aftermath of the Enniskillen bomb in 1987

Mr Burns accepts that bad things could have followed on from the bombing were it not for the leadership provided by Gordon Wilson, who helped broaden the reach of the Spirit of Enniskillen throughout the world.

"What we were trying to do was to encourage not just community relations but an understanding of the respect you can have for people of a different faith or culture," he added.

Those representing the Protestant and Catholic faiths in the town have played their part in salvaging some of the cross-community spirit that existed prior to the bombing.

Monsignor Peter O'Reilly and Dean Kenneth Hall's churches face each other at the top of the town just above the Hollow.

When they speak about the events of 30 years ago they do so virtually, as one voice, and they also talk about one community in Enniskillen.

"We don't forget about the past but we've got to try to learn from it and build together some hope for the future," said Dean Hall.

Those who died in the attack were all Protestant and included three married couples along with a reserve police officer and several pensioners

"Of course it's difficult because there are always those who do not want to mix.

"Our job is to work with each other and share with each other and to see difference not as a dividing factor but as something that can enrich us and from which we can learn."

Monsignor Peter O'Reilly and Dean Kenneth Hall's churches face each other

Monsignor O'Reilly agrees that the togetherness that existed within the local community prior to the bombing was sorely tested.

"The amount of hurt and shame that people felt, my God it was an awful shock," he said.

"It was a wake-up call not only for this part of the island but for the rest of it as well.

"The narrative of separateness that had developed particularly since the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising seemed to reach it's absolute expression here."

The cenotaph in modern times

Monsignor O'Reilly added: "The logic of it was played out in the Enniskillen bomb and I think it gave everybody pause for thought, for examination and indeed for repentance when that happened.

"Because people said: 'We need something else. This is not who we are. We need a different narrative - we need to explore what we have in common.'"

Five years ago, the Queen chose Enniskillen to make her own statement, crossing the street from St Macartin's Cathedral to St Michael's - the first time the monarch had visited a Catholic church on the island of Ireland.

The Queen met victims of the IRA bombing in 2012

"It was a few small steps but it was major strides ahead," said Dean Hall.

"It was a very big thing for Enniskillen and she set an example for many to follow and she has asked us again how we were we following up on what she had done."

Monsignor O'Reilly stresses that it wasn't just a one-sided welcome for the Queen that day.

"It was a lovely manifestation of the fact that there can be unity even in separateness or distinction," he explained.

"Unity doesn't have to mean uniformity. Tell me any house where everybody agrees perfectly and completely under the one roof. The secret is being able to see through to the humanity of each person.

"This lets you realise there's something more important and more basic than any difference of opinion or any past division that there might have been."

Denzil McDaniel was the former editor of the Impartial Reporter

A former editor of the Impartial Reporter in Fermanagh, Denzil McDaniel, has his own thoughts on how the people of the area have dealt with the horror of what happened 30 years ago.

"I think Enniskillen held its breath at that time," he said.

"This is a town that's always had good community relations, but an event of that magnitude left people waiting to see what was going to happen.

"We're standing here beside the cenotaph 30 years on and while the community has moved on, there are people still suffering physical and psychological pain and we have to be be mindful of that as well."

A man runs from the scene carrying children

No one is suggesting that Enniskillen has a monopoly on the suffering inflicted by the Troubles.

But for a time, the eyes of world fell upon this historic and picturesque Fermanagh town wedged between Upper and Lower Lough Erne.

Today, people still look to here for lessons learnt from the past and directions towards a shared future at peace.

- Published26 June 2012

- Published8 November 2012

- Published8 November 2017