Politics review: A year of dramatic change and stalemate

- Published

You couldn't make it up - Charles Dickens pondering Northern Ireland politics?

If Charles Dickens visited Stormont during 2017 he might have been tempted to describe it as both the best of times and the worst of times.

During this year of dramatic change and enduring stalemate, the main Northern Ireland parties experienced some exhilarating highs and a few emotional lows.

Dickens' encapsulation of the ups and downs of life served as a foreword to his Tale of Two Cities.

Snap election

There were more than two cities involved in our political saga. Belfast, where Stormont collapsed in January, remained a scene of grim-faced deadlock.

Brussels saw drama as the UK's divorce from the EU played out with some hard bargaining over cross-border trade and the Good Friday Agreement.

Both London and Dublin provided the backdrops to further high-pressure negotiations and trenchant ultimatums.

For the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the best of times was undoubtedly the snap election in June, which left them holding the balance of power at Westminster.

Done deal at Westminster between Theresa May and the DUP

Deputy leader Nigel Dodds and Sir Jeffrey Donaldson took a leading role in negotiating a £1bn deal in return for the party's 10 MPs propping up Theresa May in Downing Street.

The Westminster victory, which included gains in South Belfast and South Antrim, represented an incredible turn of fortunes for DUP leader Arlene Foster.

The year had begun with Mrs Foster losing her job as first minister following Martin McGuinness's resignation as deputy first minister.

Crocodile controversy

The collapse of the executive led by the two politicians was the most dramatic consequence of the angry recriminations triggered by a potentially costly green energy scandal.

The worst of times for the DUP came in March when the party lost 10 seats in the Stormont election triggered by the fall of the power-sharing executive.

Some of the decline could be explained by a reduction in the assembly's overall size from 108 to 90 seats.

However, the DUP lost its assembly veto, unionists lost their overall majority and Sinn Féin came within a single seat of the top spot.

The close result followed a bad-tempered campaign, dominated by exchanges over the Renewable Heating Incentive (RHI) controversy.

Mrs Foster also rejected passing an Irish Language Act, arguing that republicans were like crocodiles and if you fed them any concession, they would keep coming back for more.

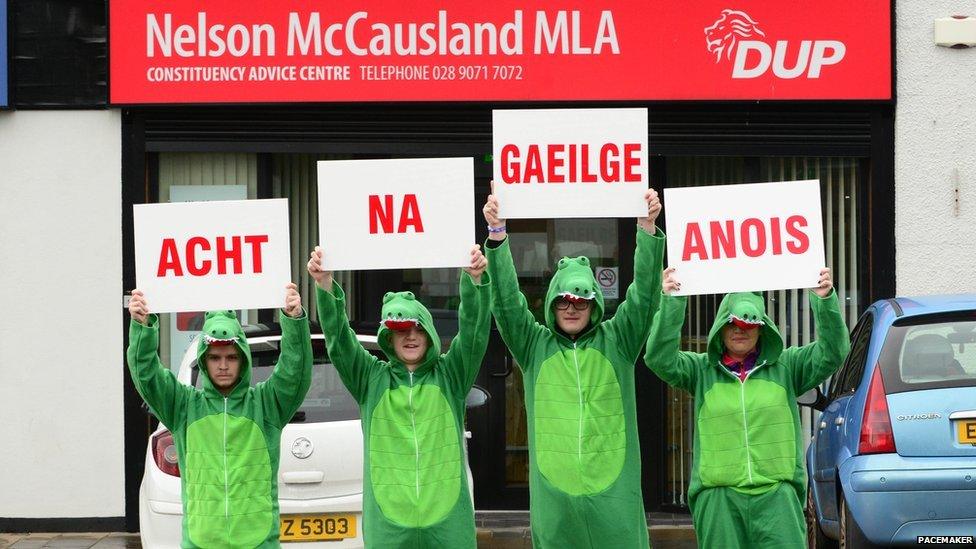

A snappy protest

Sinn Féin claimed Mrs Foster's disparaging language, dressing up activists in crocodile outfits and pledging to bite back.

The result, which left the DUP with 28 assembly members and Sinn Féin with 27, emboldened republicans to adhere strictly to their "red lines".

In the talks that followed, they insisted the DUP should agree to the Irish language legislation Mrs Foster had ruled out.

Thousands demonstrated in favour of same-sex marriage in July

In addition, they demanded progress on the introduction of same-sex marriage - something the DUP had previously blocked - and the release of funding for inquests into deaths during the Troubles.

The DUP resisted these demands, arguing that all the parties should return to power sharing and resolve their differences in parallel.

By the end of the year these arguments remained unresolved.

Martin McGuinness served as Northern Ireland's deputy first minister for 10 years

For Sinn Féin, the March election may have been the best of times. But the worst of times also came that same month with the loss of their chief negotiator, Martin McGuinness.

After a life that spanned leading the IRA and meeting the Queen, he succumbed to a rare condition, amyloidosis, at the age of 66, and was accorded something close to a state funeral as a massive crowd watched his coffin being carried through the streets of his native Londonderry.

Former US President Bill Clinton addressed the congregation inside Derry's St Columba's church, telling mourners: "If you want to continue his legacy, go and finish the work he has started."

Mr McGuinness didn't live to see his party triumph at the Westminster election in June.

Michelle O'Neill served as agriculture and health minister in the Northern Ireland Executive

The party's leader in Northern Ireland, former health minister Michelle O'Neill, led both their assembly and Westminster campaigns.

Sinn Féin took both Foyle and South Down from the SDLP and Fermanagh & South Tyrone from the Ulster Unionists. The result meant that all the border constituencies are represented by Irish republicans.

The joint advances of Sinn Féin and the DUP removed the SDLP and Ulster Unionists entirely from Westminster's green benches. Given Sinn Féin's abstentionism, this means only unionists represent Northern Ireland in the Commons chamber now.

The SDLP and Ulster Unionists suffered setbacks not just at Westminster but also at Stormont.

Mike Nesbitt stood down after a disastrous election result for the UUP

UUP leader Mike Nesbitt took responsibility for the failure of his experiment with opposition and resigned. His job was taken by Robin Swann.

Colum Eastwood hung on as SDLP leader despite two disappointing elections.

Alliance held its own at Stormont, although the party's relatively new leader Naomi Long failed to get back to Westminster.

The UK government insists its confidence and supply deal with the DUP in the Commons does not interfere with its ability to steer discussions on restoring Stormont in a balanced manner.

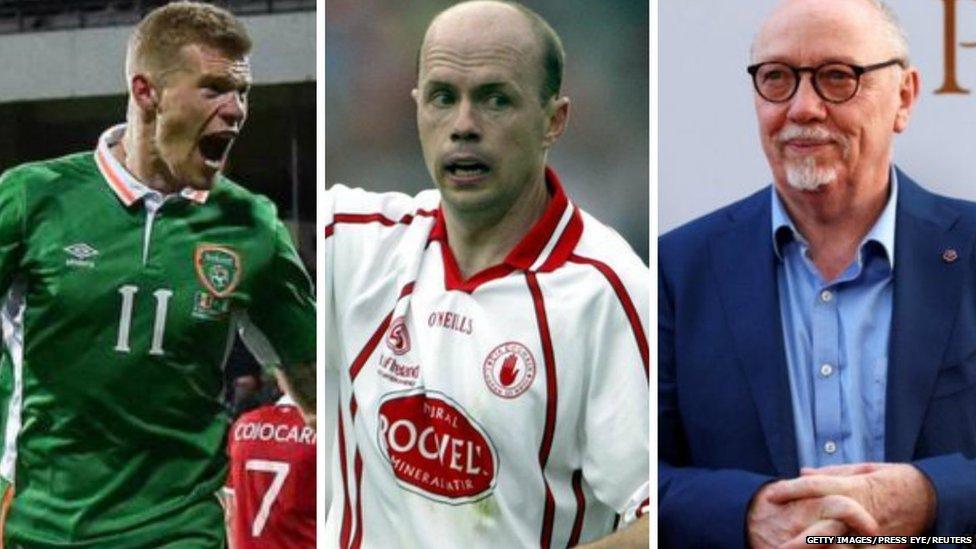

Republic of Ireland footballer James McClean, former GAA player Peter Canavan and filmmaker Terry George are among those who signed the letter to the taoiseach

But many nationalists beg to differ - at the end of the year a group of "civic nationalists" wrote to the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, asking him to defend their rights.

Northern Ireland Secretary James Brokenshire has avoided - so far - alienating nationalists by implementing direct rule from London. However, Westminster has had to step in to pass a Stormont budget and the absence of ministers led to tensions over issues such as public sector pay.

Strong position

Meanwhile, public anger has been simmering over assembly members being paid for not doing their jobs.

The involvement of the DUP in temporarily blocking the Brexit negotiations illustrated the strength of their position at Westminster.

The party claimed a victory by toughening up guarantees on the future economic integrity of the UK. This came as Theresa May negotiated a move forward to phase two of the Brexit talks.

The Irish border was as a major issue at the Brexit negotiations

A letter of comfort from the prime minister to the people of Northern Ireland - overwhelmingly aimed at unionist concerns - may serve to underline the impression that, without Stormont, London increasingly speaks for unionists and Dublin for nationalists.

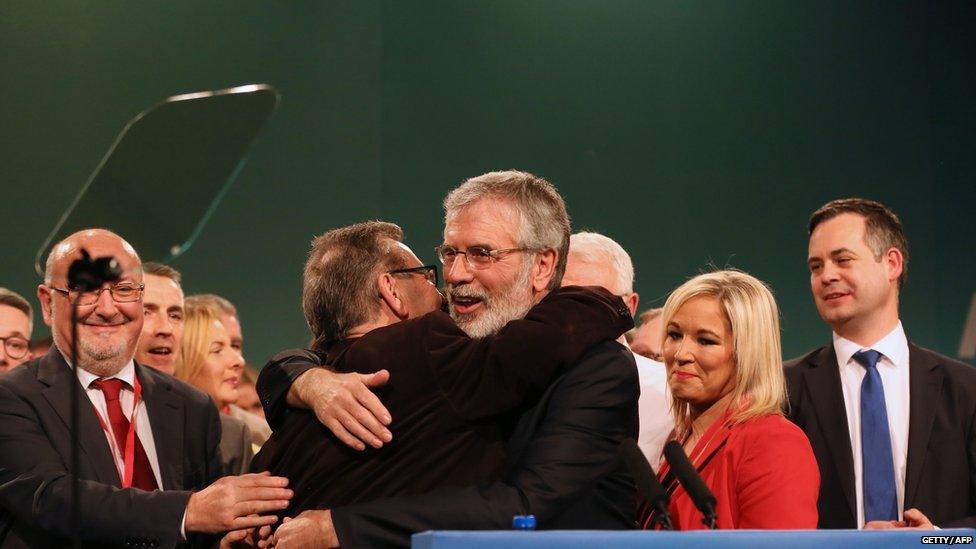

In Dublin, Gerry Adams announced in November that he was stepping down as Sinn Féin President after 34 years.

Assassination attempts

Mr Adams' life, like that of Martin McGuinness, mirrored the history of the Troubles.

He represented the IRA in talks with the government as a young man, survived imprisonment and assassination attempts, negotiated peace deals and was hailed around the world as a statesman.

As he announced his departure, Mr Adams continued to stir controversy - reviled by unionists and admired by his supporters.

Mr Adams is surrounded by party colleagues after his announcement

Gerry Adams is bowing out at 69 years of age to make room for a new generation - at the time of writing Sinn Féin's 48-year-old vice-president Mary Lou McDonald is the racing certainty to replace him.

Sinn Féin hopes Ms McDonald will enable the party to make even greater advances in the Dáil (lower house of the Irish parliament), where they now lie in third place behind Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil.

But when it comes to generational change, Fine Gael has already done its bit, replacing 66-year-old Enda Kenny with 38-year-old Leo Varadkar.

A doctor by training, Mr Varadakar took over as taoiseach in June.

Leo Varadkar said his government would be "one of the new European centres"

Young, gay, and with an Indian father, Mr Varadkar provided a fresh image for Irish politics, while his tough Brexit negotiating stance towards the end of the year proved he had substance as well as a new style.

Will 2018 be an age of change or an age of continuing stalemate?

Can the secretary of state put off direct rule much longer?

Could underemployed MLAs face a pay cut in 2018?

And how long will MLAs continue to get their full pay?

Change seems guaranteed when it comes to Brexit, but you would not bet against stalemate at Stormont, as both Brexit and the continuing inquiry into the energy scandal may make movement on restoring devolution difficult in the short term.

- Published7 November 2017

- Published5 February 2018