Rugby rape trial played out beyond courtroom

- Published

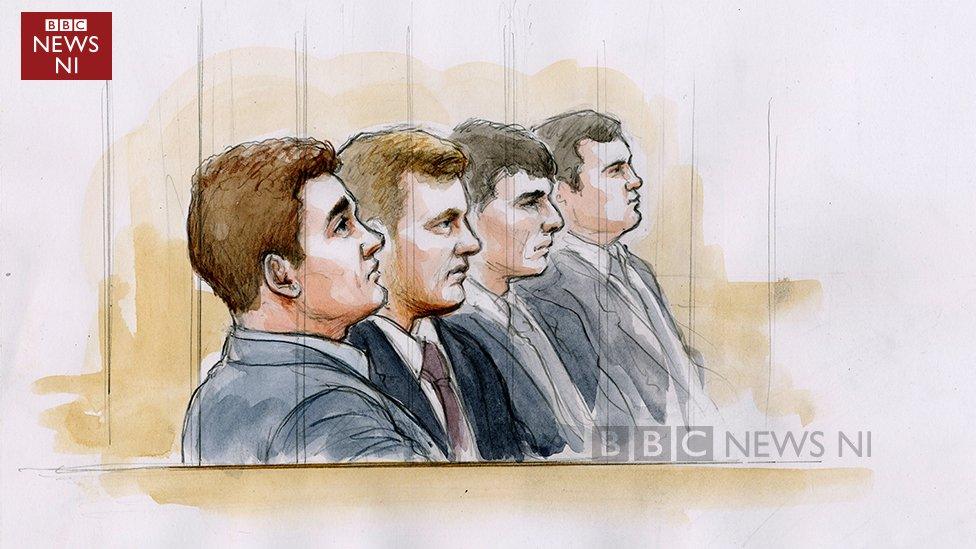

Blane McIlroy, Stuart Olding, Paddy Jackson and Rory Harrison denied all the charges against them

In the courtroom, it was all about the bedroom.

Day after day, hour after hour, the discussions centred on what happened on Paddy Jackson's bed between 03:30 and 04:30 BST on a Tuesday at the end of June 2016.

However, one point was made clear from the outset - this was not a court of morals, this was a court of law.

It was irrelevant whether the jury approved of young people, who barely knew each other, being involved in sexual activity in Paddy Jackson's bedroom.

The jury's task was to decide whether a crime had been committed.

"I was handled like a piece of meat," the young woman at the centre of the case told the court. She was 19 at the time of the alleged assault.

"There was not one bit of my body that they did not touch."

Gossip did not stop

The trial hinged on consent.

After nine weeks, the court of law finally reached its conclusions

Many people following events from a distance made up their minds before the trial began.

Rumours about the case, many of them false and malicious, swirled around Belfast for months.

Stories about the woman.

Stories about the men.

Stories about a video.

Even when the trial began in Court 12 and the facts started to emerge, the gossip did not stop.

Idle speculation about the case became a new sport around Belfast.

Judge Patricia Smyth warned the jury not to listen to "fireside lawyers" giving their opinions on social media.

In spite of the warning, commentary continued - even from some prominent public figures.

The four defendants entered the dock for the first time at 10:47 GMT on Monday 29 January.

'Best decision I've made'

Paddy Jackson went in first. Stuart Olding sat beside him, then Blane McIlroy, then Rory Harrison, then a security guard.

Two days later, the 21-year-old woman who said she had been raped by two of them entered the court.

There was no possibility of eye contact: She was shielded by a curtain placed around the witness box. However, there was a camera beside her and her face could be seen on screens around the court.

She spoke clearly and confidently.

"It's the best decision I have made," she said, about going to the police and reporting the rape allegations.

Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding watched her on the screen. They did not react.

They waited for their turn to give evidence.

First up was Paddy Jackson. He took off his jacket, had a sip of water from a white paper cup, walked the 22 steps towards the witness box and lifted up the Bible.

He looked at the court usher and swore an oath to tell the truth.

Paddy Jackson has won caps for Ulster and Ireland

It was day 27 of the trial.

It had all begun back in winter; this was now spring. The suit he had worn on day one had been replaced by a blue jumper and an open-neck shirt.

He was witness number 23. The trial was already going on much longer than expected.

Five weeks had been set aside; it ended up taking almost twice as long.

So what took up so much time?

Arguments and delays

The questioning of the complainant, for a start. The young woman was in the witness box on eight separate days.

She started giving evidence on 31 January, and finished on 12 February.

Her days in the witness box were not all full days. She was given regular breaks. Nonetheless, she spent a long time answering questions as she faced cross-examination from four separate defence barristers.

There were a number of other reasons for the length of the trial.

Legal arguments over the admissibility of evidence took up a large amount of time and sickness of jurors delayed proceedings.

To try to make up lost time there was a legal rarity, a Saturday sitting of the Crown Court.

Drinking scrutinised

There was no video of what happened, in spite of the rumours that circulated before the trial.

Five different people told the court they were in the bedroom, at some stage, during the night. Every aspect of their evidence was painstakingly explored.

Thirty different witnesses gave evidence, including 10 police officers, two doctors and a taxi driver.

Such was the level of detail that the underwear the woman wore that night was produced in court, passed around and examined.

Dozens of text and WhatsApp messages were scrutinised.

The amount of alcohol each person consumed on the night was also analysed.

Much was made of the fact that Stuart Olding had 23 drinks - eight cans of Carlsberg, four pints of Guinness, two gin and tonics, five vodka and lemonades, three shots and a beer from the fridge in Paddy Jackson's house.

He told the court he was "pretty drunk but still coherent".

The jury went on a visit to the house but the media were not allowed to go along.

Inside Court 12, there were only eight seats for reporters. The rest of the media, many of them from Dublin, had to sit in the public gallery.

The trial has been a major news story for its duration

Most days, the 100 seats in the public gallery were filled, not just by the friends and family of the four defendants but by onlookers.

One man travelled by train from Coleraine every day to watch proceedings. A judge from Texas in the United States came one day, during a trip to Belfast on holiday.

By the end of the trial, patience on all sides was wearing thin. The summing-up process took more than a week.

There was a final flurry of appeals to the jury.

Prosecution barrister Toby Hedworth QC looked at the four defendants then turned to the jury and said: "The lads. Legends? You decide."

One by one, the four defence barristers said the answer was "not guilty".

Judge Patricia Smyth had the final word before sending the jury out to deliberate.

Their verdicts marked the end of the trial.

After nine weeks, the court of law finally reached its conclusions.

Now the court of public opinion will, no doubt, have its say.