Brexit and the Irish border: The experts' verdict

- Published

- comments

With eight months to go until the UK officially exits the European Union, the Irish border remains one of the most difficult problems to solve.

BBC News NI has asked a number of Brexit experts for their assessment of the current state of play in the negotiations, and whether a deal between the EU and UK on the border can be done.

Dr Katy Hayward - Reader in sociology at Queen's University, Belfast

Dr Hayward has research experience on the impact of the EU on the Irish border and peace process.

At this stage in the Brexit process, it is remarkable that the two sides fundamentally disagree on so many basic points.

Essentially, the European Commission sees Brexit as a divorce, whereas the UK government views it as a move towards a more "open" relationship - keeping the benefits of marriage with fewer of the commitments.

So, while the EU is focused on the Withdrawal Agreement (to ensure an orderly separation), the UK's eye is on the Future Framework (setting out the aspirations for the new UK-EU relationship).

The EU approaches Brexit as a legal and technical process; the UK approaches it as a bargaining and political process.

Would you notice if you crossed the Irish border? (Video from 2017)

Hence, officials in Brussels are continually pointing to the clock, aware of the need to navigate the Withdrawal Agreement through its institutions to take legal effect.

In contrast, those in London are less stressed about the broken timetable and more confident in the possibility of last minute breakthroughs.

Such differences clash most dramatically on the Irish border.

In the absence of a common UK-EU understanding about the wider process, it has proven difficult to build on the shared commitments made in the Joint Report of December 2017, external.

Instead, each side suspects the other of using Northern Ireland's unique Brexit predicament to lever a final arrangement for the whole of the UK.

In the meantime - for all the talk of contingency planning for a no-deal exit - real damage is being done by the persistent uncertainty and stubborn disagreement about what it is that Brexit actually means."

The EU approaches Brexit as a legal process, while the UK sees it as more of a bargaining process, says Dr Katy Hayward

Dr Graham Gudgin - chief economic advisor at influential right-leaning think tank Policy Exchange

On the face of it, the Chequers white paper solves the Irish land-border issue.

Indeed, this is exactly what the Chequers arrangements were designed to do.

The arrangements include a customs union with free trade in goods, regulatory alignment in goods and procedures for ensuring that goods flowing through the UK to the EU pay the correct import duties and observe the correct regulations.

These complex arrangements mean that no consignments of goods need to be stopped at any UK border including that in Northern Ireland.

This would solve the problem for goods, but in Ireland that is not the whole issue. Much of the problem involves small traders living close to the border, many of them suppliers of services rather than goods.

Farming on the border

This might include retailers, and certainly includes electricians, plumbers and many others. For services, the UK will seek such things as mutual recognition of qualifications.

Since all such qualifications are already recognised, this should hardly be an issue but such is the determination of the EU to make life difficult, that it will need to be tortuously negotiated.

There are two problems. One is on the Irish side of the border.

The UK has promised no new infrastructure and can deliver regulatory alignment in NI in sectors where it matters, but the EU has to reciprocate on the Irish side.

The Taoiseach asserts he has such an undertaking from Brussels on infrastructure, but Brussels denies this in its normal spirit of using the border as a bargaining chip rather than as a problem to be solved.

The really big problem is that the white paper is unlikely to survive opposition from either pro-Brexit Tories or from the EU. The proposed arrangements are too complex and the white paper too full of wishful thinking.

It is another poorly crafted document of the sort we have unfortunately come to expect from the UK civil service. It will need to be replaced in the Autumn, including new proposals for the Irish border.

Dan O'Brien, chief economist at the Institute of International and European Affairs (IIEA), in Dublin

The Northern Ireland border backstop is now the central issue threatening to scupper Brexit negotiations between the UK and the EU.

The EU's position is that Theresa May's government must make a legally binding commitment to keep Northern Ireland in the EU's customs territory if the UK's future relationship with the EU causes any change to the way the border arrangements on the island of Ireland currently function.

The British government has rejected this, arguing that no government could concede to such a demand - it would mean having to impose an internal border between Northern Ireland and Britain; and it would mean that EU law would remain supreme over UK law in Northern Ireland.

The binary nature of customs and international trade powers makes the impasse intractable.

The reason for this lies in the nature of customs and international trade powers which mean a country (or region) can only be in one customs union and single market at a given time.

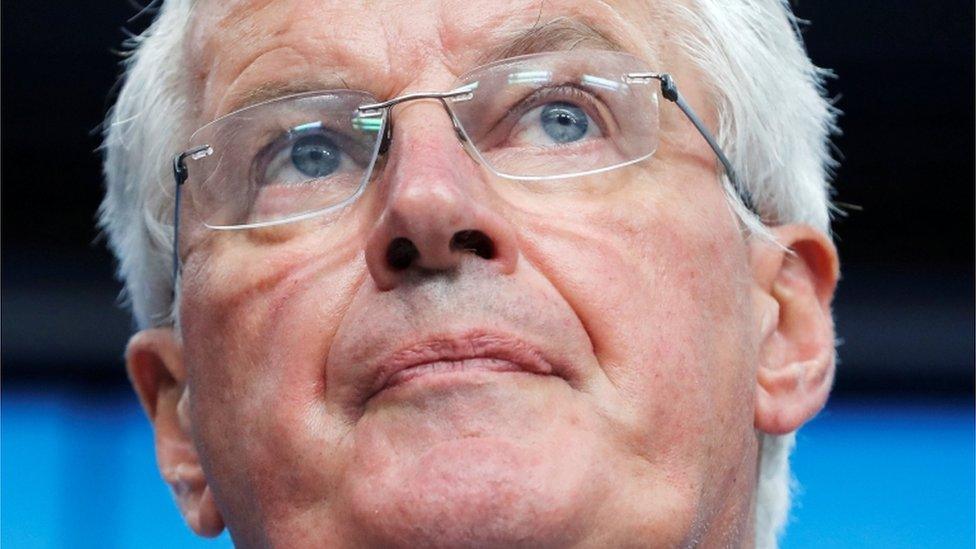

Michel Barnier has said there can be no Brexit withdrawal agreement without a backstop option for the Irish border

These powers, unlike others such as the power to tax, cannot be devolved to regional governments.

This is to be seen even in countries organised along federal lines, such as the US and Switzerland, where many powers are devolved away from central government.

In neither country do the states and cantons respectively exercise powers relating to international trade deals with other countries, a power which is the exclusive preserve of their federal governments.

Nor can they enact laws which lead to regulatory divergence as this would threaten the integrity of their national single markets.

It appears increasingly clear that the impasse over the backstop in the Brexit negotiations will only be resolved if one side makes a very significant change to its current position.

If that does not happen, it is difficult to see any agreement emerging on the UK's departure from the EU.

Dr Kathryn Simpson - Senior lecturer in Political Economy, Manchester Metropolitan University

The problem the prime minister faces is that the Chequers deal is too soft for Brexiteers, and not soft enough for Remainers.

Consequently, the UK has experienced intense political instability with the resignation of senior Cabinet Ministers and narrow governmental wins in Parliament to Brexit legislation. As a result, much discussion has taken place about a hard Brexit and a no-deal Brexit.

There is a substantial difference between the two. A hard Brexit allows the implementation of a Withdrawal Agreement agreed within the Article 50 process which will allow a transition period.

A no-deal Brexit would see no legal basis for UK-EU relations after 29 March 2019, and would result in the immediate and extensive disruption to trade, travel and security cooperation.

The problem the prime minister faces is that the Chequers deal is too soft for Brexiteers, and not soft enough for Remainers, says Dr Kathryn Simpson

Both a hard and a no-deal Brexit have wide-ranging implications for Northern Ireland and the backstop option which was agreed at the end of Phase One of negotiations in December 2017.

The backstop option, which would allow Northern Ireland to remain as part of the customs union and European single market for goods, will only take effect if the future UK-EU trade deal is inadequate to avoid border checks and controls between the UK and the EU.

However, the Irish border is about much more than trade.

The UK Withdrawal Agreement cannot be finalised without a guarantee to avoid a hard Irish border.

That is irreversible. A hard Brexit and a no-deal Brexit are directly at odds with the backstop option.

Whether the backstop is specific to Northern Ireland as insisted by the European Commission, or whether it is UK-wide, will only be decided by continued Brexit negotiations.

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar has said there can be no time limit placed on the backstop

Brexit is like a Rubik's Cube; it is multifaceted, complicated and frustrating. The process of negotiating a favourable UK-EU future relationship at the same time as the terms of withdrawal was always going to be a difficult undertaking.

The European Council meeting in October is crucial as it will finalise the UK's Withdrawal Agreement - the legal basis for UK-EU relations on Brexit Day on the 29 March 2019.

Autumn 2018 will determine whether Brexit will be hard, soft or indeed whether the UK will leave the UK with no-deal.

Northern Ireland is at the centre of that debate.

Sir Martin Donnelly - Former permanent secretary at the Department for International Trade

The UK is leaving the European Union at the end of March. The Republic of Ireland is remaining a member. For the last two years the EU has made clear that there will be no transition agreement to 2020 without a fallback arrangement to keep the Irish border as open as it is now. Permanently.

The British Government made a treaty commitment twenty years ago in the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement to an open border. Last December it repeated that pledge, regardless of the outcome of the wider Brexit negotiations.

Will the bridge that unites the two villages be used to divide them?

If the rest of the UK leaves the customs union or single market, then logically there will have to be checks in the Irish sea.

So either all the UK agrees to stay in the single market; or something else happens that nobody has thought of yet.

If we don't come up with a legally binding deal that can go into the transition agreement the UK will be leaving without any deal - the hard Brexit option.

That would be bad for Europe, awful for Ireland and a disaster for the United Kingdom.

On the plus side, having a watertight fallback which guarantees an open economic border is good news for jobs and investment in Northern Ireland, and arguably provides a competitive advantage over the rest of the UK.

The political problem is how we all get there by next March. I think we will, but only if Northern Irish voices are heard loud and clear in Westminster.

- Published2 August 2018

- Published16 October 2019

- Published19 July 2018

- Published25 July 2018

- Published15 May 2018