Eamonn McCann: The long march to Stormont

- Published

Eamonn McCann went from fiery speaker to assembly member after 50 years

"The only thing that ever got us anywhere in this town was not parliamentary manoeuvre. In my view, it certainly wasn't armed struggle. What it was, was the sound of marching feet."

In 1968, 25-year-old Eamonn McCann earned the reputation of a fiery speaker at the forefront of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland.

After standing unsuccessfully for more than five decades, he was eventually elected in March 2016 at the age of 73 to the Stormont Assembly as a People Before Profit politician.

By March 2017, he had lost his seat - the result of a snap election.

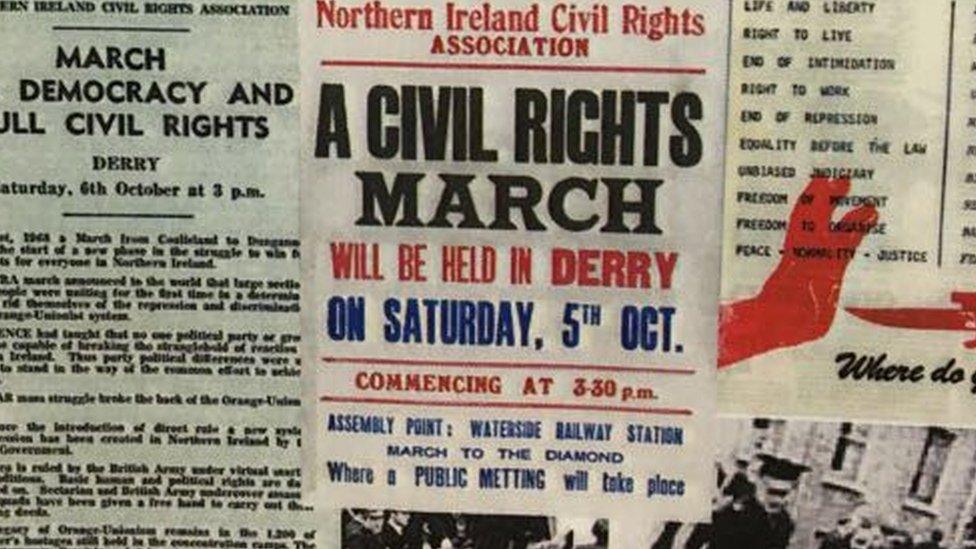

Civil rights march in Derry on the 5th October 1968

A BBC Northern Ireland documentary looks back over his career and reveals the inside story of his 10 months as an assembly member, rising from street activist to politician and back again.

By Eamonn McCann, political commentator

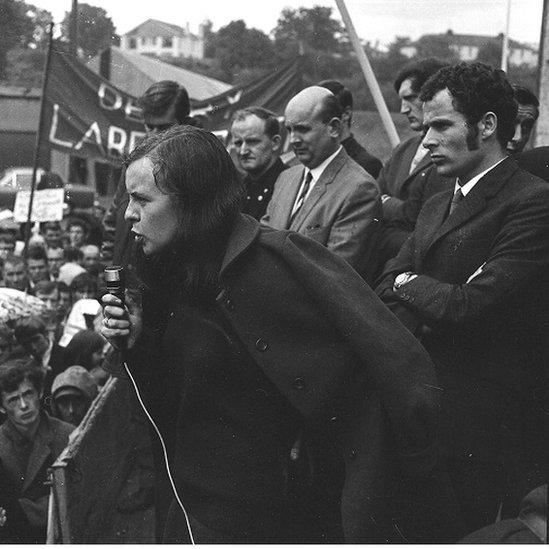

Eamonn McCann, speaking at an event in the Bogside area of Derry in April 1969

I don't claim that the account in the film is the only truth of the period.

Some who were as close to the action as I was, will recall events in a different perspective. That's always the way of it.

I can only say that in long conversations and interviews with producer-director Margo Harkin, I gave it my best shot.

In my own view, the most valuable thing about the film is that it provides an account of the developments in Derry which led to 5 October 1968 march which may take some by surprise.

It doesn't navigate between the standard lines of the Orange-Green narrative.

Bernadette Devlin, who later became an MP, addressing the crowd at a civil rights march in Derry in 1969, alongside Eamonn McCann

But then that march, which provides the peg on which the piece is hung, didn't fit into the standard narrative either.

The film shows that the impetus for the march came not from a strategy for uniting Ireland, but from working-class agitation over housing and jobs.

In Derry, at least, the key precursor of the civil rights campaign was the Derry Housing Action Committee.

The 5 October 1968 march in Derry was banned by the Northern Ireland government

For months, we had been disrupting civic life in Derry, invading the council chamber, blocking roads, squatting homeless families into empty houses and much else. When there were arrests, we protested at police stations.

When some were charged with public order offences, we picketed the courthouse. And when picketers were arrested, we picketed over that.

As 1968 wore on, the numbers supporting and taking part in street activity steadily grew.

What happened on 5 October signalled that we'd reached critical mass. Highlighting this sequence is long overdue.

The ripening of local politics matched the rise of radicalism around the world.

Derry in November 1968 at a civil rights demonstrations, where protesters are seen confronting RUC officers

All of us in the group that organised the 1968 march saw ourselves not as nationalists or unionists, but as leftists.

We looked for example and inspiration, not backwards into Irish history, but outwards into the wider world, for example, the black civil rights movement in the United States, the campaign against the American war on Vietnam, the student uprising in France and the resistance of the people of Prague to Soviet imperialism.

The civil rights movement widened the perspective of huge numbers who had been hemmed in by oppression.

It held out the possibility of a society where political loyalties were not solely or mainly dictated by communal loyalties but by attitudes to the rights of working class people to issues of justice and equality, to injustice not just in Derry but everywhere.

That vision was to fade too fast and too soon. But it gave us a glimpse of what was possible, of what yet could be. It still inspires.

What I remember most now of the things which filled my days half a century ago, is the visceral feeling of being part of a vibrant mass, transforming the politics around us by our own collective action.

Eamonn McCann: A Long March, will be broadcast on BBC One Northern Ireland, on Monday 8 October, 9pm

- Published18 August 2018

- Published19 April 2018

- Published6 May 2018