October 1968: The birth of the Northern Ireland Troubles?

- Published

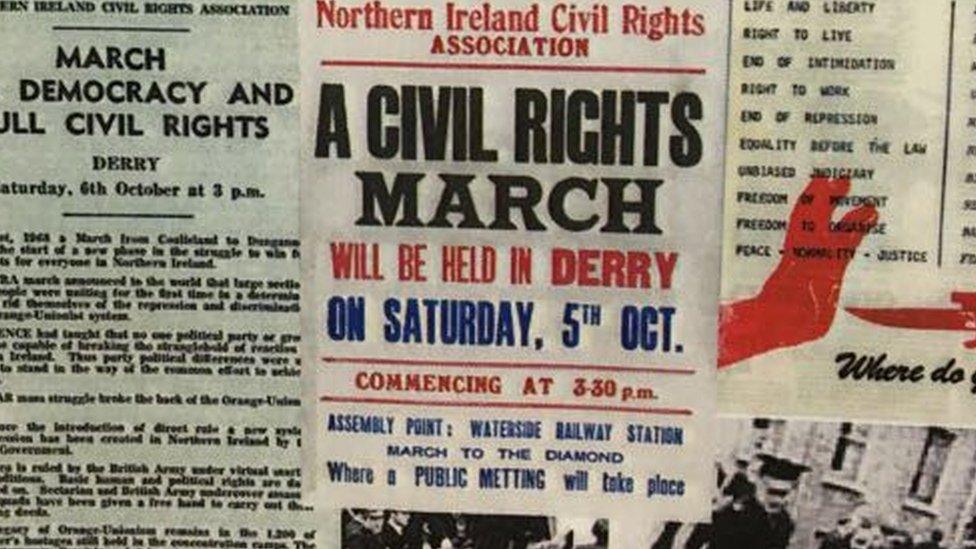

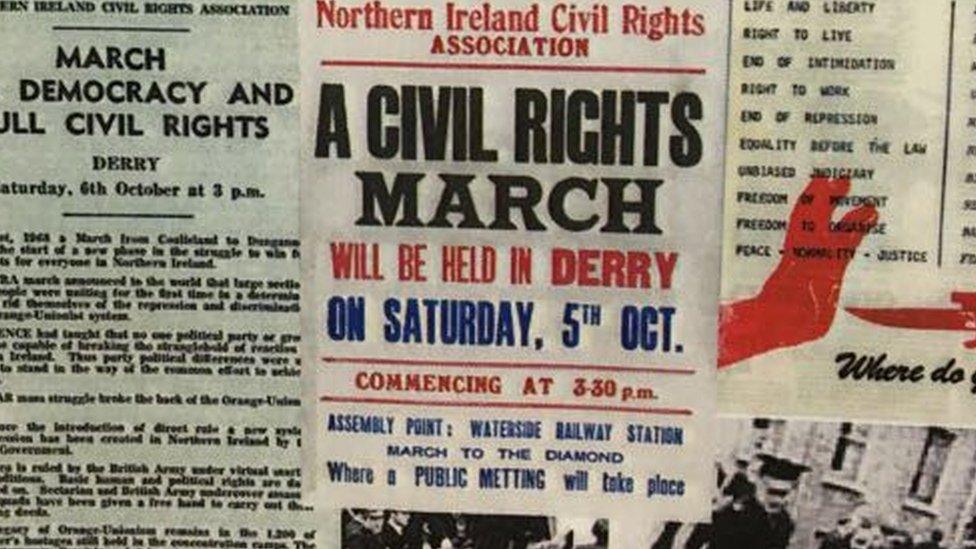

Civil rights march in Derry on the 5th October 1968

"A policeman came in with a baton in his hand with the blood dripping off it."

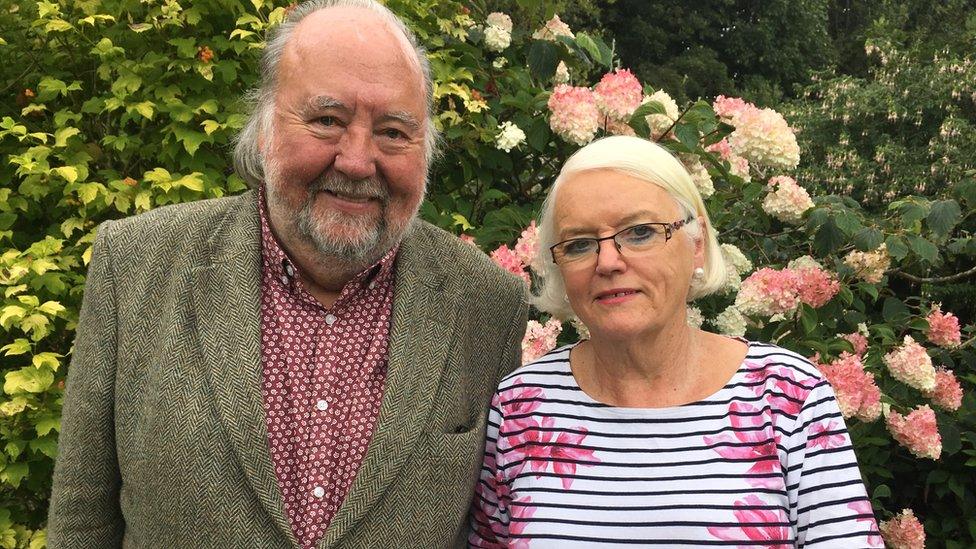

Deirdre O'Doherty was a trainee radiographer in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, in 1968, and was among the campaigners preparing to take part in a civil rights march on 5 October.

Half a century may now have passed, but she said she "will never forget" that day.

Her testimony is one of many that features in a new BBC series to mark 50 years since the date widely regarded as the day the Troubles in Northern Ireland began.

It was a time of protest across the world, with campaigners calling for social change in Paris, Prague and the US.

That atmosphere inspired activists in Northern Ireland who demanded an end to gerrymandering and discrimination and called for "one man, one vote".

The October 1968 Duke Street March in Londonderry had been organised by local activists, with the support of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA).

NICRA had formed in 1967, and drew inspiration from the campaign for equal rights in the US.

Their first march in Dungannon in August 1968 raised concerns around housing in County Tyrone, highlighted by one case, in particular, when a single Protestant woman was allocated a house ahead of Catholic families.

'Screaming'

In October 1968, their attention turned to the unionist-controlled Londonderry Corporation, and its housing policy.

Campaigners, Ms O'Doherty included, saw the local authority's housing policy as discriminating against the nationalist and Catholic population by the mainly Protestant/unionist-controlled local authority.

The previous day, the October march was banned by the Northern Ireland government.

It would go ahead, in defiance.

As campaigners gathered in the Waterside area of Derry, rows of police officers from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) waited.

Deirdre O'Doherty was a trainee radiographer who ended up working in Altnagelvin hospital on 5 October 1968

"We joined the march at the old railway station," Ms O'Doherty recalls.

"It was to start at 3.30pm. I walked up towards the Craigavon Bridge to see what the delay was.

"There were rows of RUC officers and there was a lot of debate going on. Then a riot broke out. People were screaming."

Baton-wielding RUC officers tried to break up the march and water cannon was deployed in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

It was all captured by a film crew from the Irish national broadcaster, RTÉ, and was beamed around the world.

'Found a voice'

As "police battered people left, right and centre," Ms O'Doherty sought solace in a nearby café.

"A door opened and a policeman came in with a baton in his hand with the blood dripping off it," she recalls.

"He was young. He looked vicious. I never saw a face with so much hatred in all my life. I thought that was it. He turned though, and walked out."

As the violence continued, the trainee radiographer flagged down an ambulance.

She hitched a lift to her work.

She "x-rayed about 45 skulls that day", among them the then West Belfast MP Gerry Fitt, who had travelled to take part in the march.

Protesters regularly took to the streets to call for civil rights in the late 1960s

Grainne and Michael McCafferty were students in 1968.

Like many young people, they felt empowered by education, and were emboldened by calls for change across the world.

"There was a much wider spread of people who were educated and in a position to say 'we do not find this acceptable'," Grainne remembers.

"There was a climate of unease and demand for change and the civil rights movement was borne out of that. That led into 5th October.

"We had found a voice, stood up for ourselves, refused to accept any longer this yoke that had been placed on us by the state."

Grainne and Michael McCafferty were on Duke Street on 5 October

Grainne's husband, Michael, said the march had "started quietly".

"It was only when we got near and realised there was a police blockade that tensions rose," he says.

Grainne recalls: "When the baton charge started by the police we turned to flee, and I remember a wall of policemen across the road blocking our exit route - and a sinking feeling that this is serious trouble - then people started to run in fear."

Mrs McCafferty says 5 October marked a "turning point."

The 5 October 1968 march in Derry was banned by the Northern Ireland government.

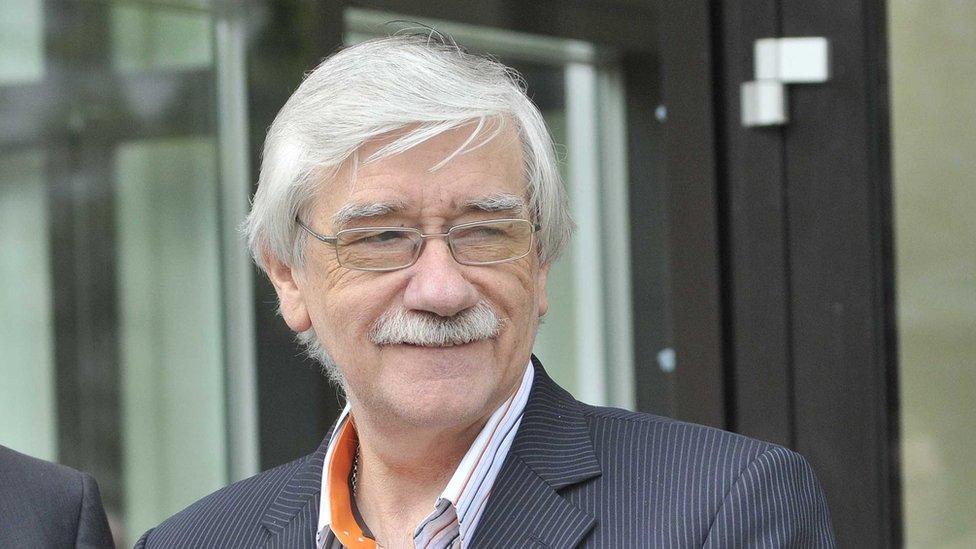

For Terry Wright, then a pupil at one of the city's Protestant schools, it was also a significant moment.

Mr Wright, who would go onto serve as deputy chair of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), believes it was the day relationships between Protestants and Catholics changed.

"I don't remember labels being particularly important in my life then, but it all changed in 1968 on 5 October," says Mr Wright.

He said his Protestant contemporaries could identify with the early demands of campaigners, that there was a shared sense of injustice.

'Disengaged'

"There were conversations going on at school being very critical of the Unionist Party and some would have identified with civil rights," he says.

"Something that is quite often forgotten is that when we talk about 'one man, one vote', there was quite a number of the unionist population that didn't have a vote because they weren't homeowners.

Terry Wright was a teenage school boy at a Protestant school in Derry in 1968. He would later serve as deputy chairman of the UUP

"A lot of young people felt 'unionism isn't doing what it needs to do', and would have identified with civil rights. I remember attending some of the civil rights meetings in Guildhall Square."

Ultimately, the sense of grievance shared between Protestant and Catholic neighbours, would dissipate.

"But once the violence started, and there began to be attacks on the Fountain [housing estate], it became sectarian. At least that was the perception. That's when a lot of young Protestants and unionists who identified with civil rights disengaged," he says.

A BBC Radio Foyle series features a range of witness testimony and reflections on 5 October.

The series, called '68, begins on 1 October at 08:55 BST and at 16.55 BST on BBC Radio Foyle and Radio Ulster, with podcasts available on the BBC Radio Foyle website.

A 30-minute radio documentary called ' The Day The Troubles Started' will air on BBC Radio Foyle on Friday 5 October at 13.30 BST.

- Published18 August 2018

- Published19 April 2018

- Published6 May 2018

- Published14 October 2017