Shankill bomb: A dark day amid talks of peace

- Published

The Shankill Bomb: 23 October 1993

Brian Rowan was BBC News NI's Security Correspondent at the time of the Shankill bomb. Nine people were killed in the 1993 attack in Belfast, as well as one of the IRA bombers. 25 years on, the journalist looks back on the attack, the violence of 1993 and the secret talks which eventually lead to peace.

None of us knew what peace would look like; how it would be achieved or how and when it might arrive.

We certainly couldn't see it or read it in the words and the headlines of 1993.

The Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) had threatened to "intensify and widen" its campaign "to a ferocity never imagined".

And, as the year unfolded, its 'war commentary' detailed its attacks on republicans and the nationalist community.

At the time, [UFF leader] Johnny Adair, spoke to me of attacking Sinn Féin at "the top, middle and bottom of the ladder".

The statements became more political - referencing the Hume-Adams-Dublin talks of that time and a pan-nationalist front in "ruthless pursuit of the common goal of a united, Gaelic Ireland".

A UFF codeword "crucible" - now defunct - was the means of authenticating the many statements of this time.

The IRA said it was "determined to exact a price" from loyalists - that there would be "no hiding place"; this warning part of an interview just days before the Shankill bomb.

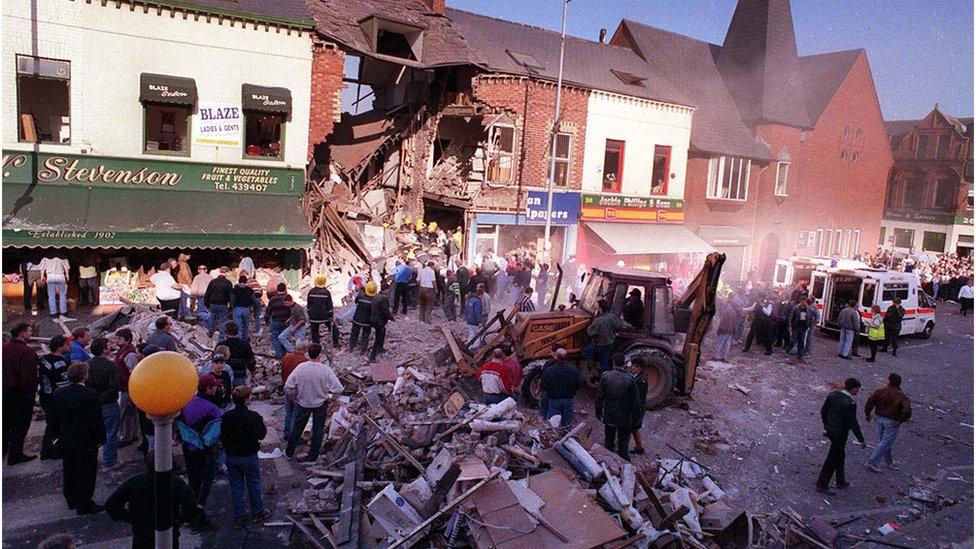

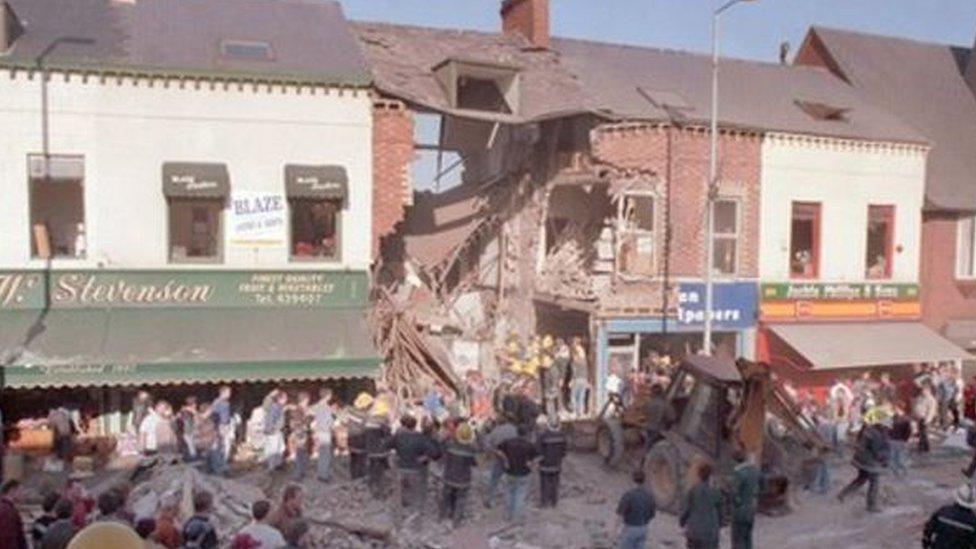

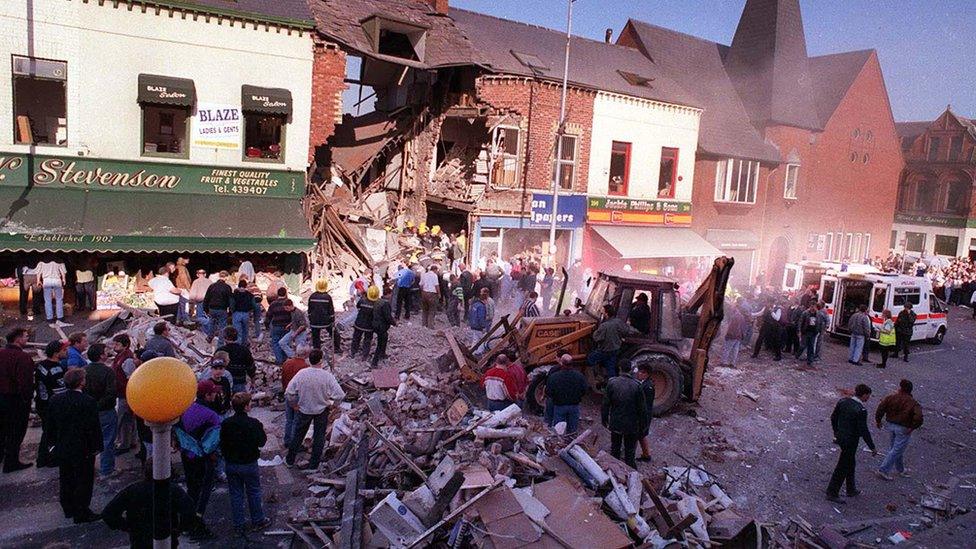

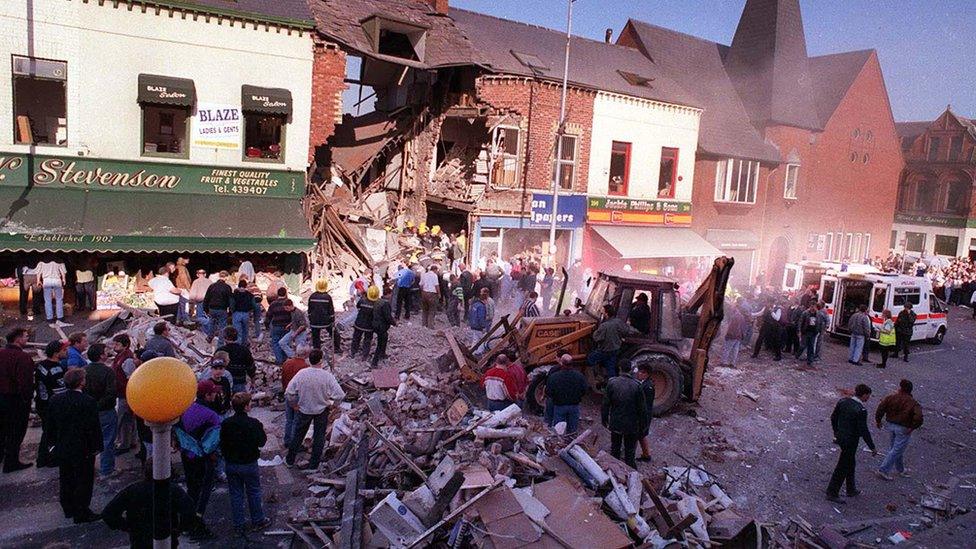

The bomb exploded in a fish shop on a busy Saturday afternoon

As the carnage of that attack became clear, the IRA spoke of an operation that "went tragically wrong".

But had it gone tragically wrong or was it the inevitable outcome of their actions?

It was a busy Saturday on the Shankill Road.

The bomb was set to go off within seconds.

The bomb caused devastation in the Shankill Road

There was a stated intention to target loyalist leaders in an upstairs office above Frizzell's fish shop in that tight block of buildings.

It soon emerged that the office was empty.

But if those Ulster Defence Association, external (UDA) leaders had been there on the day of the Shankill bomb, and if any credible warning had been given by the IRA, then they would have escaped - down the stairs and away from danger.

As part of my work at the BBC, I had visited that office on occasions to speak with UDA leaders.

Any warning was never going to be sufficient to clear the area. This is the lie in the IRA statement of that day.

They must have known they were going to kill and injure civilians.

Indeed, many years later, one of the IRA's most-senior leaders in that period accepted that the nature of the attack meant there would be "collateral damage".

In the context of the legacy discussion and process now under consideration, the IRA should correct the statement of October 1993 - as many other statements from the many other sides should be corrected.

The IRA will also have known that a loyalist response to the Shankill bomb was inevitable.

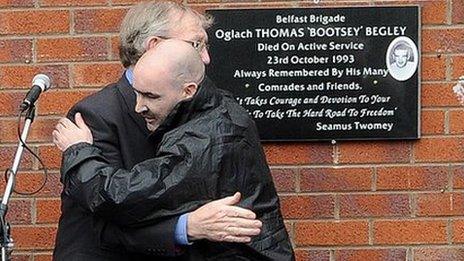

Wreaths were laid earlier in October to mark the 25th anniversary of the bomb

Secret talks

Within hours of the attack, a UFF statement telephoned to the BBC warned that all active service units would be "fully mobilised" and that the nationalist electorate would pay "a heavy, heavy price for today's atrocity".

There was a killing rage involving both the UFF and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), and the names of Martin Moran, Sean Fox, James Cameron, Mark Rodgers, Gerard and Rory Cairns and then those targeted in the Greysteel pub shootings were added to the list of the dead.

In 1993, this place was walked to its very edge.

It was the year of the Warrington bomb.

The year when Gordon Wilson, whose daughter Marie was killed in the Enniskillen bomb of 1987, met the IRA in a plea for peace.

The year of an IRA video statement calling on the British government "to pursue the pathway to peace or resign themselves to the inevitability of war".

A year when the UVF attempted to smuggle a huge arms shipment into Northern Ireland as part of its "determination to carry on the war against the IRA".

And it was a year of secret draft political texts linked to those Hume-Adams-Dublin talks and then the headline revelation of contacts between the British government and the IRA leadership.

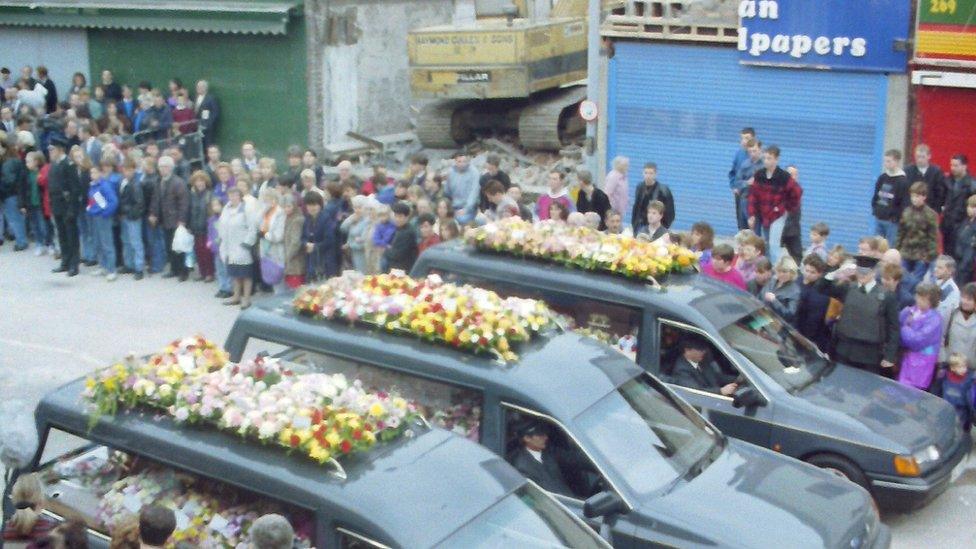

Crowds of mourners gathered to remember those killed

Ceasefires

This is the context of the period, including this talk of peace.

It was hard to believe and see in all that was happening at that time, but within a year of the Shankill bomb and all that followed, both the IRA and the Combined Loyalist Military Command had announced ceasefires.

Organisations that had spoken out of the dictionary of war, had now found new words and a new beginning.

Perhaps the convulsion of October 1993 - the madness and sadness of that time - had made people stop and think, step back from the edge.

But what a bloody price the dead of that period alongside the long list of lost lives paid for that peace.

- Published21 October 2018

- Published19 October 2018

- Published20 October 2018

- Published27 January 2016

- Published20 October 2013