Soldier to shoe-maker - centenarian's WW2 memories

- Published

Bob Lingwood spent his 21st birthday as a soldier in France

Bob Lingwood was born in London just weeks before World War One ended.

He didn't imagine war would be part of his life, but he had his own reasons for joining up at the age of 19.

"I didn't join because I was loyal to the crown, as it were, patriotic. I joined because I wanted to learn about motor engines. Motor engines then were like computers are today."

When the World War Two hostilities began, he was called up.

"I spent my 21st birthday in France in 1939," he recalled.

Useless trenches

"For six months, we were virtually digging trenches, which were useless, they were never used.

"We did get leave back to London, but it was more dangerous to go back to London and the air raids than what we were experiencing in France."

Bob's job was to lay telephone wires to allow communication between different sections of the Army.

In early 1940, he was in Brussels, when things began to wrong.

"We were confronted by two armoured vehicles. We were no match for the Germans.

"I was in charge of the unit and I had no choice but to surrender."

A selection of Bob's medals

Bob and his men had to march towards a prison camp, collecting more prisoners, mostly French and Belgian soldiers, en route.

They reached the town of Aalst in Belgium, when Bob saw his chance.

"Our guard was distracted," he said.

"I'd already noticed as we entered the town, that I could see our troops on the other side of the river.

"I said to my section, 'come on lads, we'll make a run for it'."

'Bullets struck bridge'

Accompanied by some of their fellow French and Belgian prisoners, they made a break for the river, only to find the bridge had been blown up and was submerged not far below the surface, ending yards from the riverbank and safety.

"We managed to get all our soldiers, some were non-swimmers, on to the bridge.

"The Germans reappeared and opened fire on us. I could hear the bullets hitting the iron framework and so on top of the bridge.

"We got to the other side safely."

At that early stage of the war, concerns were running high about armies being infiltrated, and so the men were interviewed by a British officer.

Bob was awarded a military medal for bravery after saving the lives of about 30 men in a daring escape from the Germans

"We were interrogated, in fact. And he said, 'I'm sorry, but I can't accept all your story', so I was actually taken prisoner by both sides in the one day."

It took four days for Bob to establish his identity, when he was recognised by members of another unit.

Then, he and his men made their way to the beaches at Dunkirk to await the evacuation.

However, their boat came under attack from German dive-bombers and he was wounded in the back with shrapnel.

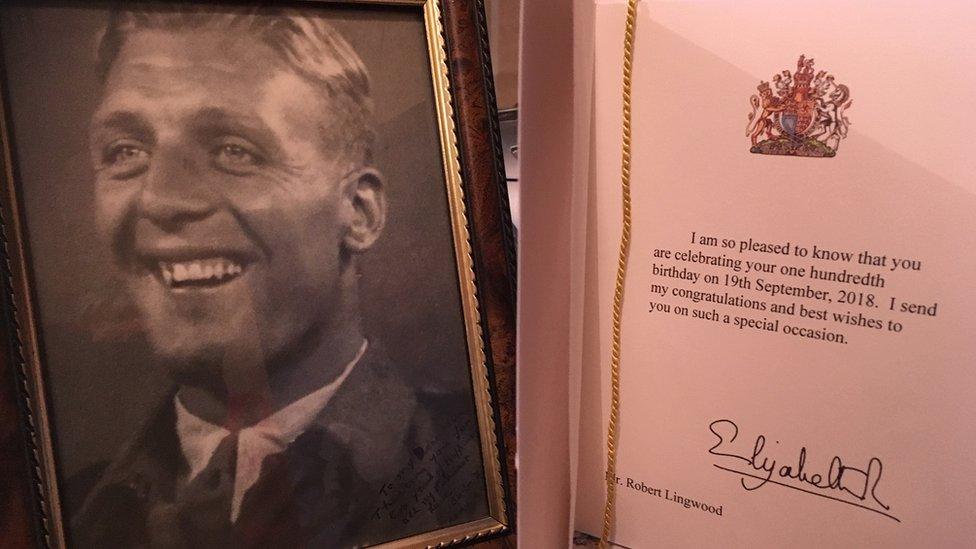

Bob turned 100 in September and received a card from the Queen. He is photographed during World War Two.

Bob spent several weeks in hospital, and discovered - via a newspaper - he had won a medal for his bravery in leading the escape.

He was given a new assignment in Catterick, where he was to report after his sick leave ended.

But he found out his old unit was reforming in Aldershot, so he went with them when they were sent to Northern Ireland.

"Northern Ireland was a place we had hardly ever heard of," he said.

"We landed on the 11th of July, we were moved up to Lisburn and the next day we were confined to camp.

"We hadn't a clue what it was about, but we could hear drums."

On 13 July, they were allowed to leave the camp and the first order of business was to phone home.

Bob and Emma (centre) on their wedding day. The bride wore turquoise, as white was not available

"I managed to get through to my father," Bob said.

"He said: 'Where are you?' and I said, 'Northern Ireland.'

"He said: 'The police and the Army were here looking for you today, you've been posted as a deserter.'

"But it was only because I hadn't reported back to Catterick."

The soldiers were made welcome, with the camp emptying out on a Sunday, thanks to many invitations to tea.

Bob found himself invited to one house, where he was to meet his future wife, Emma.

They were married in 1942, just before he was sent to the Middle East.

Soldier to shoemaker

In 1945, Bob was demobbed and went back to the shoe-making trade he had followed his father into before the war.

He and his wife settled into life in London, raising their son and daughter.

When the government announced subsidies for deprived areas, he moved the now-grown-up family to Northern Ireland and set up a branch of his employers' factory in Omagh, County Tyrone.

He ended up employing 200 people, making 8,000 pairs of shoes a week.

An image of Bob with the interior of the card from the Queen

The factory closed when manufacturing became cheaper overseas, but Bob and his son opened another, smaller enterprise, making specialised components for shoes and employing about 30 people.

At the age of 70, Bob felt retirement was beckoning.

But the industry had other ideas.

"I'd been retired a few weeks when I got a phone call from Reebok," he said.

"So I got a job with them as a consultant and got sent all over the world for about five years.

"I reckon that was a perfect ending to a great career in shoe-making."

Award winning gardener

Since then, Bob has filled his time with an award-winning garden and being involved in many community groups in Omagh.

Up until his early nineties, he was still running and exercising five days a week.

Things may have slowed down a little now, but he will play a special part in the Armistice Day commemorations in Omagh this weekend, as a member of the British Legion.

"This year, I've been asked to inspect the parade," he added.

"I'm to lay the first wreath and after that, I'm to take the salute of the parade, which is really an honour.

"On the final day, there were 5,000 soldiers killed when Armistice was declared. And I think of the millions of people, men that died.

"It's beyond comprehension. It's terrible."

- Published6 November 2018

- Published3 November 2018