NI politics and policing 'still in tug-of-war'

- Published

The Police Service of Northern Ireland came into being in 2001

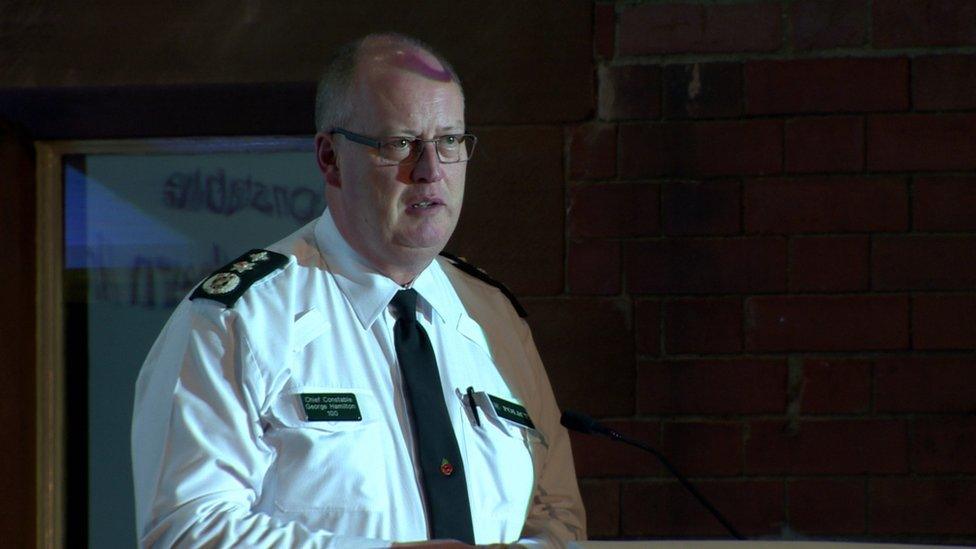

The most senior officer in the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) says politics is now "more polarised, more entrenched and less creative" than it was 20 years ago.

Chief Constable George Hamilton was reflecting on two breakthrough moments in the peace process - now almost two decades ago.

Firstly, in September 1999, the report of the Independent Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland, chaired by Lord Patten, which signalled major reforms and the beginning of the end of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

Then, in November of the same year, there was the negotiation that put in place a power-sharing executive at Stormont.

That was new policing alongside new politics.

PSNI Chief Constable George Hamilton recently announced his retirement

Twenty years later, the political institutions at Stormont have collapsed in a heap and, in a long standoff that began in 2017, there is no certainty about their future.

The chief constable, who will retire in June, also knows that policing is again under the sharpest of spotlights.

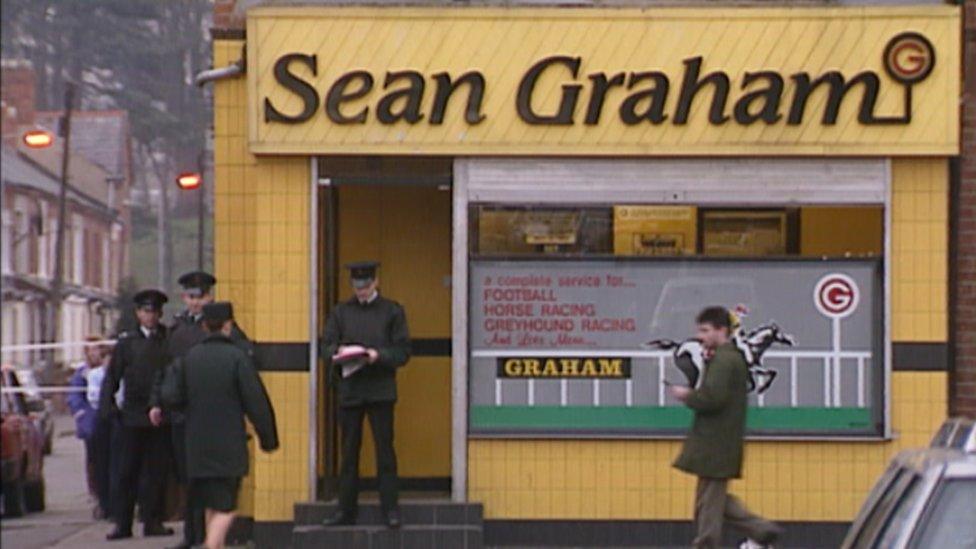

In the headlines - another disclosure controversy - the PSNI's failure to disclose all documents relating to the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) killing of five men in a Belfast bookmakers in 1992.

The PSNI failed to reveal significant information about the gun attack on Sean Graham's shop

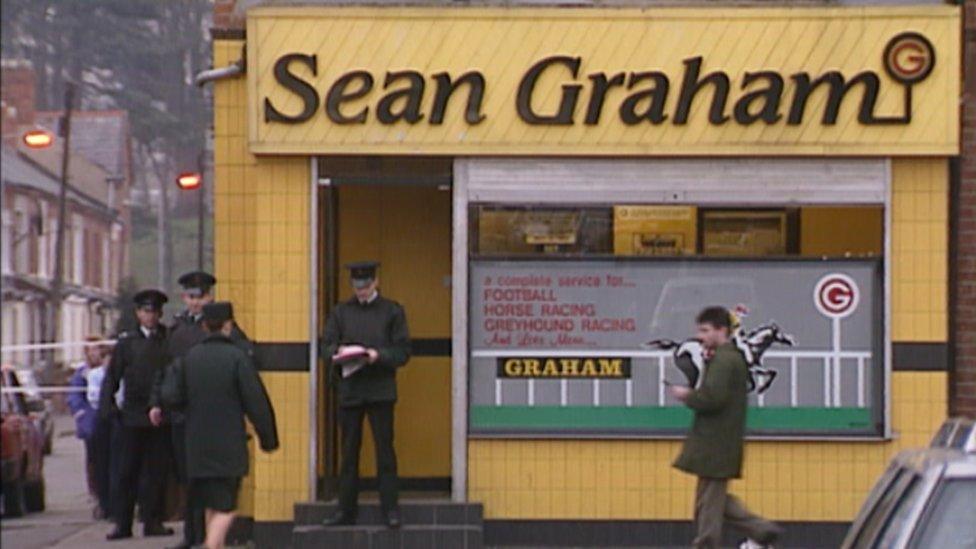

Sinn Féin MLA Gerry Kelly believes the "huge issue of legacy" is "the primary reason for the loss of confidence".

"It's contaminating the new beginning to policing - the recent issue around disclosure is not an isolated incident," he adds.

This latest controversy over the disclosure of information will mean a delay in a number of reports on investigations by the Police Ombudsman, Michael Maguire.

Sinn Féin's Gerry Kelly said there was a belief that "there is dead hand holding back disclosure"

Gerry Kelly also cites the case of murdered solicitor Pat Finucane and how it took several investigations and reviews over a long period of years to achieve the information now in the public domain, and not yet the full picture, "which leads to a belief that there is dead hand holding back disclosure".

These continuing battles have opened old wounds and arguments about confidence in policing, about credibility and the composition of the service in terms of Catholic representation throughout its ranks.

Political class

"The irony of the political class criticising us," comments a senior PSNI officer.

No government in Northern Ireland for more than two years.

And no process yet in place to address the questions of the conflict years, despite being two decades beyond the 1998 Good Friday peace agreement.

"Twenty years ago, we didn't realise the problem the past was going to be," Mr Hamilton says.

"There was no commission to deal with the past, no architecture to deal with the past."

The lack of an executive at Stormont since January 2017 has left legacy issues in the hands of the Northern Ireland Office

The political negotiation that stretched from 1997 through to late 1999 was silent on this.

"Either they thought they had solved the past or they didn't think at all."

That observation from Mr Hamilton takes us back two decades - to the early release of paramilitary prisoners under the Good Friday Agreement, the decommissioning of weapons, and, subsequent arrangements to assist in the recovery of the remains of "The Disappeared" - those murdered and secretly buried by the IRA.

Those steps in the political process included a Sentence Review Commission, an Independent International Commission on Decommissioning, an Independent Commission for the Location of Victims' Remains and Lord Patten's Independent Commission on Policing.

Procrastination

The transformation of policing in Northern Ireland has proved to be a long process

It was not until 2007 that a wider consultation began on the past with a report from a consultative group two years later.

Delay and procrastination have been the features of the legacy debate since then.

"Politics needs to take this burden of the past away from us," says the PSNI Dep Ch Con Stephen Martin.

"We can't relieve ourselves of it.

"We have no desire at all to hold on to it - it is contaminating the new beginning that we have all invested so much in."

Decisions are in the hands of the Northern Ireland Office.

Will they proceed with legislation to implement the legacy structure that emerged from political negotiations in 2014, including a new Historical Investigations Unit (HIU) and an Independent Commission on Information Retrieval (ICIR)?

A Historical Investigations Unit would have a caseload of about 1,700 Troubles-related deaths and aim to complete its work in five years, while an Independent Commission on Information Retrieval would only look for information if asked to do so by families.

Twenty years after the Patten report politics and policing are still in a tug-of-war

A former vice chairman of the Policing Board, Denis Bradley, recently added his voice to the calls for legacy cases to be taken out of the hands of the PSNI.

"Policing has been damaged as we know, as headlines will tell you over the past month - or over the past 10 years - by its involvement in trying the deal with legacy," he told BBC Radio Ulster.

After another recent consultation, there is no indication as yet on the next steps, but rather a suggestion that some further discussion or consultation may be needed.

"We need to identify where the political blockage is," says Gerry Kelly.

"It is with the British government, who have not produced the legislation to set this up.

"We don't need another consultation. It's another stall. Everybody has been consulted."

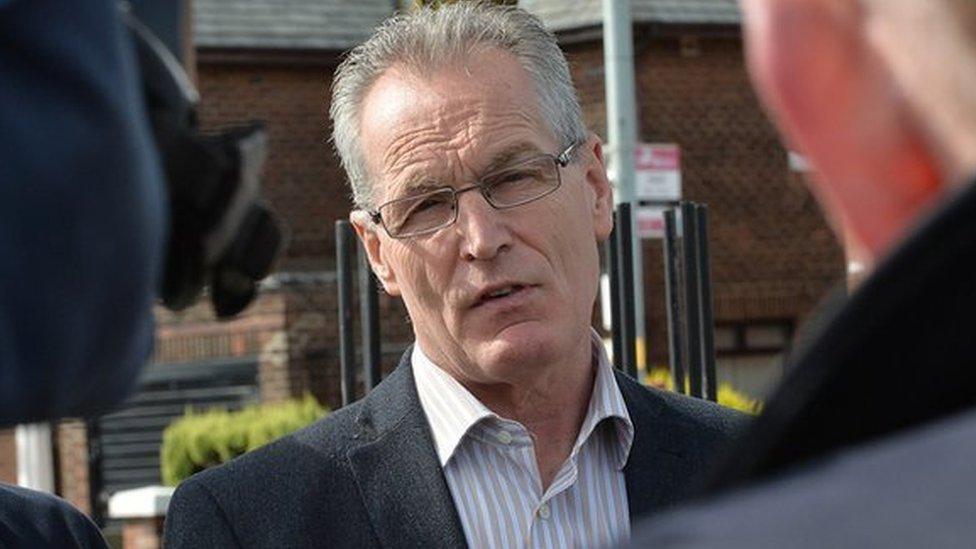

'Taking the politics out of policing' was a key part of Chris Patten's 1999 report

Back in 1999, when Lord Patten set out his commission's proposals for the new beginning for policing, he identified a significant challenge.

"We believe that it is possible to find a policing solution to the policing problem, but only if you take the politics out of policing. That is a key part of this report - the depoliticisation of policing."

In 2019, this remains a challenge - politics and policing are still in a tug-of-war.

'Losing faith'

Mr Hamilton has argued, throughout his tenure, that the past must be taken out of policing.

In his community, Gerry Kelly sees the damage that is being done in terms of confidence in the PSNI.

"The view is certainly hardening against the policing body and people are losing faith at a high rate," he said.

"The confidence within the victims and survivors community is at nil.

"We have a situation where the chief constable himself has said he wants this taken away from the PSNI. The [legacy] structures need set up."

Twenty years on from the Patten Report the question of the legacy of the Troubles remains a potent issue

The new beginning is poisoned by this constant rewind into the conflict period and, in the running arguments, today's policing can be made look and feel like old policing.

Mr Hamilton believes that progress has been "good" in the areas dealt with by the Patten Report but, in other areas not addressed in that report, there has been a lack of progress and in some respects policing has been left "in a worse position".

He is thinking and talking about the past and specifically the absence of an alternative approach.

The fallout is a legacy war, not a healing or reconciliation process. Too often, the past becomes the present.

So in a landscape of so many commissions, why has there not been one specific to legacy?

It was a recommendation in the 2009 report of the consultative group co-chaired by Archbishop Robin Eames and Denis Bradley.

Earlier this week, the Department of Justice announced it is to set up a legacy inquest unit in the Coroners Service to process Troubles inquests.

It aims to speed up legacy inquest arrangements and deal with outstanding cases.

Dissident threat

However, if the focus now is just on who will replace Mr Hamilton as chief constable this summer, then it will miss the point.

The question of legacy, the dissident republican threat now into its third decade and how to depoliticise policing are unresolved issues.

If they remain so, then the arguments of new policing versus old policing will continue.

Brian Rowan is a former Security Editor at BBC News NI

- Published1 March 2019

- Published3 November 2016

- Published25 February 2019