Belfast doctor tells of fighting Ebola in African war zone

- Published

Dr Stacey Mearns has been involved in battling two Ebola outbreaks in Africa

Imagine being a doctor fighting to contain an outbreak of one of the world's deadliest diseases.

Then imagine doing so in a war zone where more than 100 armed groups are operating.

Belfast-born doctor Stacey Mearns has just returned from North Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo where there has been an outbreak of Ebola.

It is the second time Dr Mearns, who works for the International Rescue Committee, has battled the disease.

She worked in Sierra Leone during the West Africa outbreak, which killed more than 11,300 people between 2014 and 2016.

"In West Africa, I think as a global community we left it quite late to respond," Dr Mearns said.

"By the time we had the financial resources and enough partners on the ground, the outbreak was already very out of control.

A healthcare worker sprays a room during a funeral of a person suspected of dying of Ebola in Beni, North Kivu Province of Democratic Republic of Congo

"It's been the opposite in Congo. We saw in Congo a very early response from the international community, very early entrance of partners into the response and very early funding of the response."

However, she said a big difference between the outbreaks was the dangerous political situation in DR Congo.

"In West Africa we didn't have to deal with that, those three countries [Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia] were relatively stable, whereas North Kivu has over 100 armed groups and an active conflict, so that's one striking difference that's actually made controlling the outbreak really difficult," she said.

Lessons learned

"With Ebola, you do learn how to protect yourself and the measures you can put in place to protect you from acquiring the virus.

"But with conflict, there's a whole different dimension associated with that.

"So for me, definitely I was more concerned about the conflict and fighting in North Kivu than Ebola itself."

Dr Mearns, a former NHS doctor who joined the International Rescue Committee (IRC) four years ago, said lessons learned from the earlier West Africa outbreak have been used in the DR Congo outbreak.

Ebola broke out there last year and has so far resulted in the deaths of about 700 people.

A vaccine not available during the West Africa outbreak is being used in DR Congo

"(West Africa) was the first time we'd had to deal with an outbreak of Ebola on that scale, so there was a lot of learning, a lot of tools at our disposal off the back of that outbreak that we didn't have before - for example the vaccine," she said.

"So I think it was a good opportunity to go back and work on Ebola again, but this time with a lot of new tools at our disposal and a lot of learning under our belt."

Humanitarian group Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has pulled out of the Butembo area of DR Congo due to the security situation.

In the past month, four Ebola clinics have been attacked, while a male nurse was strangled in front of his wife.

"The situation is hazardous," she said.

"I was not attacked personally, but I certainly had my movement affected. You have fierce fighting between rival factions and aid organisations being targeted directly."

Dr Mearns said some people in the area believe Ebola was deliberately introduced as a political tool to enrich those in power while rumours have also circulated that if you go for the vaccine, you are actually injecting people with Ebola.

"One of the biggest things that we learned from the West Africa outbreak was that engaging with communities in a meaningful way that builds trust is absolutely critical," she said.

"I feel like in North Kivu, eight months into the outbreak, we're still not there with engaging communities. There's still a lot of mistrust that's affecting our ability to contain the outbreak."

What is Ebola?

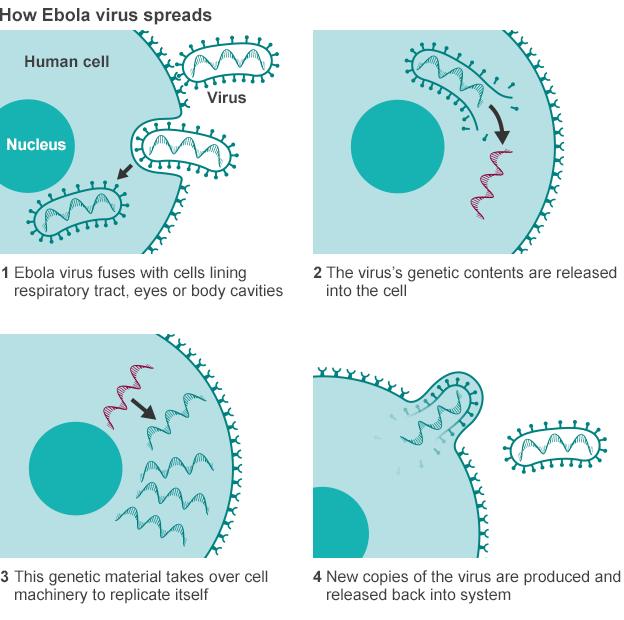

Ebola is a viral illness of which the initial symptoms can include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat.

That is just the beginning: Subsequent stages are vomiting, diarrhoea and - in some cases - both internal and external bleeding.

The disease infects humans through close contact with infected animals, including chimpanzees, fruit bats and forest antelope.

It then spreads between humans by direct contact with infected blood, bodily fluids or organs, or indirectly through contact with contaminated environments. Even funerals of Ebola victims can be a risk, if mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased.

The incubation period can last from two days to three weeks, and diagnosis is difficult.

Healthcare workers are at risk if they treat patients without taking the right precautions to avoid infection.

People are infectious as long as their blood and secretions contain the virus - in some cases, up to seven weeks after they recover.

Dr Mearns said that while, as a former NHS doctor, she had seen people die, nothing could have prepared her for the volume and pace of death she witnessed working in Sierra Leone.

"There was a period where dead bodies were just being dumped all over the hospital," she said.

Attackers set fire to an Ebola treatment centre run by Medecins Sans Frontieres in February

"I think the worst day, I saw 25 people in body bags. That was a combination of bodies dumped around the hospital and people dying inside the unit.

"It felt like everyone was just dying and that was a very tough environment to work in.

"You just see immeasurable amounts of suffering and all of that takes its toll on you.

"When I think back to West Africa, there were times of just feeling hopeless. You were seeing the outbreak worsening, feeling exhausted and tired from the work you were doing.

"I think the hardest moments are those moments of just wondering if this is ever going to end."

Dr Mearns said that the population of North Kivu had already endured much before the Ebola outbreak.

"There's been fighting there for 15 or 20 years and it's affected every facet of people's lives," she said.

"So people are understandably frustrated when they see a lot of attention and resources come in for Ebola, but not the same for the broader conditions and the violence.

More than 11,300 people died in the West Africa Ebola outbreak from 2014-2016

"We're eight months into the outbreak and we're seeing it currently spread at its fastest rate yet.

"During the last two weeks we've seen a record number of infections, so we've still got a long road ahead of us to contain and end the outbreak. And it's likely to get worse before it gets better."

International Development Secretary Penny Mordaunt said the UK was playing a key role in combating the disease.

"From helping to put specialists like Dr Mearns on the ground, to developing a vaccine - the UK is playing a crucial role in the fight against Ebola," she said.

"Disease does not respect borders, so UK aid is playing a significant role in saving lives and stopping the spread of this devastating and deadly virus is firmly in our national interest."

The dangers faced by health workers were illustrated during the West Africa outbreak when British nurses William Pooley and Pauline Cafferkey nearly died after returning to the UK in 2014 with Ebola.

Dr Mearns admitted that when she came back from that outbreak she did feel a bit "paranoid".

Dr Mearns has been doing emergency work for the last five years

"Every time you get a headache or something, you fear the worst," she said.

"Ebola is the last disease in the world you'd want to catch."

However, she added: "I've been doing emergency work now for the last five years and I'm quite accustomed to adjusting when I come back home and just being thankful for being at home.

"It certainly makes you more thankful for what you do have in your life."

- Published17 May 2018

- Published14 May 2018

- Published19 February 2018

- Published31 January