Contaminated blood inquiry: Victim's 'life of fear and anger'

- Published

Contaminated blood inquiry: 'It messes with your head'

A man who was infected by contaminated blood has told a public inquiry of a life of fear, paranoia and anger.

Hearings into what has been called "the worst treatment scandal in the history of the NHS" opened in Belfast on Tuesday.

An estimated 4,000 people across the UK were infected and thousands are thought to have died.

With allegations of a cover-up, no-one in government or the NHS has been held to account.

Paul Kirkpatrick from Londonderry, who has haemophilia, was speaking for the first time about his experience.

'Paranoid'

Mr Kirkpatrick, who is in his fifties, said he had lived a life being told he was a public health risk and had been paranoid that his children would be affected.

As a result of the infection he contracted Hepatitis B and C.

Giving evidence, he said he had felt unclean and only now as a result of the inquiry had he been offered counselling.

Over the past three decades, he said he had batted away various "clouds", including potential cancer, CJD, AIDS, never knowing what the health service would throw at him next.

He described the "shocking, confused process of passing on life-threatening information to patients" including himself, "where often information is passed on to patients because they ticked a box"

Mr Kirkpatrick said this should never be allowed to happen again.

'You want to protect your kids'

At the inquiry, Paul Kirkpatrick spoke of how the infection affected his family and his children.

He said: "My wife would follow me round the house sterilising everything to make sure there was no risk to the kids."

He added that he would not touch dummies, prepare food or allow the children to get into his bed when he had open wounds.

Mr Kirkpatrick said: "Like any parent you want to protect your kids first and foremost and both of us did that as best we could. There was fear they would be contaminated in some fashion."

Witnesses from Northern Ireland are speaking at the inquiry this week

The first UK-wide public inquiry into the scandal is being led by Sir Brian Langstaff, who was appointed in February 2018, and is looking at why thousands of people with haemophilia were infected with hepatitis C or HIV in the 1970s and 1980s.

Some people have waited 30 years for a full public inquiry.

Speaking at the start of proceedings on Tuesday, Sir Brian said the inquiry had visited Belfast "as a matter of principle", adding that it puts people first and that he was in the city to listen.

Financial support

Each of the UK nations has its own financial support scheme for infected patients.

There have been complaints that victims of the contaminated blood scandal in England and Scotland are receiving more financial help than those in Wales and Northern Ireland.

The problem dates back to the 1970s when imported blood-clotting products derived from blood plasma caused haemophiliacs and others to be infected with HIV and hepatitis.

Warnings raised as early as 1974 were ignored - now patients want to know who within the NHS and the government knew what and when.

'No stone unturned'

Christina McLaughlin's brother Seamus Conway, who was 45, died last year - he had haemophilia, which affects the blood's ability to clot.

Seamus Conway died aged 45 last year from haemophilia

His family believes his eventual liver cancer diagnosis was a direct result of having hepatitis after he was given infected blood products as a child.

Ms McLaughlin is due to give evidence to the inquiry on Thursday and said she had every faith in its chairman.

She told BBC News NI that although previous attempts at inquiries were not successful, Sir Brian had said he would "get to the truth and leave no stone unturned".

Ms McLaughlin's sister, Patricia Kelly, said she hoped lessons would be learned.

"This inquiry will get people some kind of closure but it won't bring back their family members, their sisters or brothers, their mothers or fathers," said Mrs Kelly.

"It's horrendous, but at least people will get a closure."

What is the scandal about?

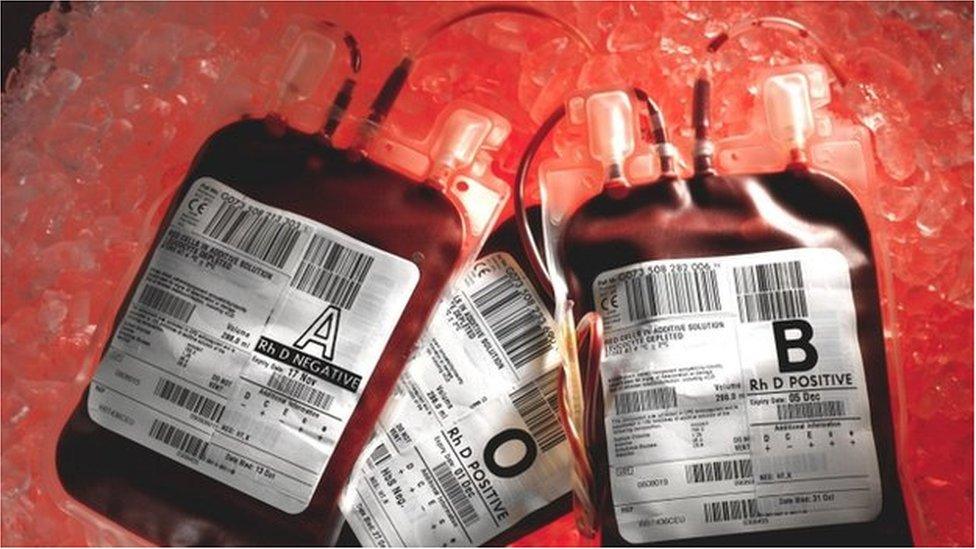

About 5,000 people with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders are believed to have been infected with HIV and hepatitis viruses over a period of more than 20 years.

This was because they were injected with blood products used to help their blood clot.

It was a treatment introduced in the early 1970s. Before then, patients faced lengthy stays in hospital to have transfusions, even for minor injuries.

Britain was struggling to keep up with demand for the treatment - known as clotting agent Factor VIII - and so supplies were imported from the US.

But much of the human blood plasma used to make the product came from donors such as prison inmates, who sold their blood.

Factor VIII was imported from the US in the 1970s and 1980s

The blood products were made by pooling plasma from up to 40,000 donors and concentrating it.

People who had blood transfusions after an operation or childbirth were also exposed to the contaminated blood - as many as 30,000 people may have been infected.

By the mid-1980s, the products started to be heat-treated to kill the viruses.

But questions remain about how much was known before this and why some contaminated products remained in circulation.

Screening of blood products began in 1991. And by the late 1990s, synthetic treatments for haemophilia became available, removing the infection risk.

Why has it taken so long to have an inquiry?

This is the first UK-wide public inquiry that can compel witnesses to testify.

It comes after decades of campaigning by victims, who claim the risks were never explained and the scandal was subsequently covered up.

The government has been strongly criticised for dragging its heels.

There have been previous inquiries. One was led by Labour peer Lord Archer of Sandwell and was privately funded.

It held no official status and was unable to compel witnesses to testify or require the disclosure of documents.

Meanwhile, the Penrose Inquiry, a seven-year investigation launched by the government in Scotland, was criticised as a whitewash when it was published in 2015.

The government announced there would be an inquiry only after it faced a possible defeat in a vote on an emergency motion.

- Published20 May 2019

- Published30 April 2019

- Published24 September 2018

- Published30 April 2019