Brexit: PM says backstop stays but boosts Stormont's role

- Published

Prime Minister Theresa May has unveiled what she called her new Brexit deal

The backstop is perhaps the most controversial part of the prime minister's Brexit deal.

It is an insurance arrangement designed to avoid a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic under all circumstances.

It would keep the UK in a "single customs territory" with the EU, and leave Northern Ireland in the EU's single market for goods.

Some MPs fear it could trap the UK in a customs union with the EU while Northern Ireland unionists think it would diminish their place in the union.

In her speech on Tuesday, the prime minister said she had listened to unionist concerns.

But she was also clear that the backstop would be staying in the Withdrawal Agreement.

Instead, she promised to give legal force to commitments that she has already made and proposed an enhanced role for the Northern Ireland Assembly - should it ever be reconstituted.

Firstly, Theresa May said there would now be a legal commitment to find "alternative arrangements" for the Irish border by December 2020.

Alternative arrangements basically mean technological solutions for the Irish border which would allow trade to flow across it unimpeded, even if the UK is outside the EU's customs union and single market.

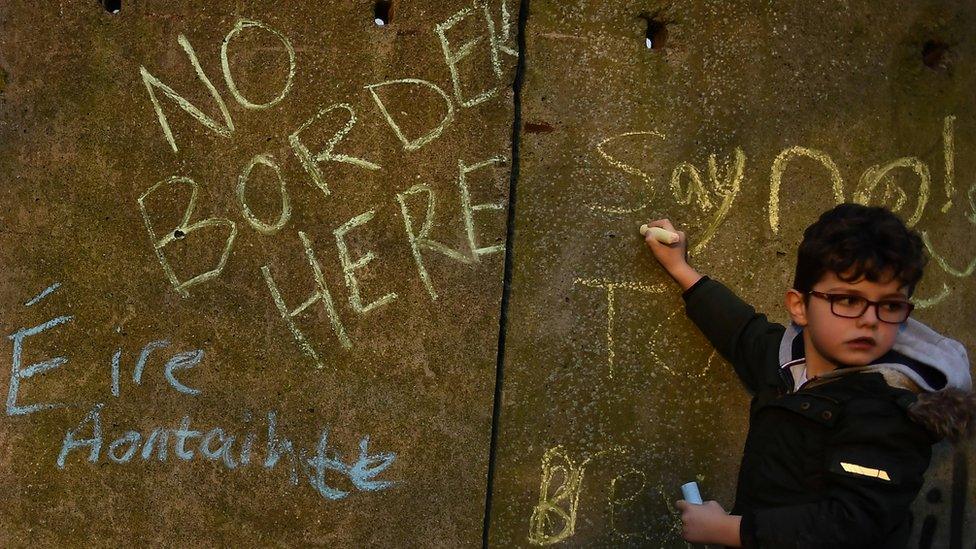

The Irish border has been one of the most contentious issues surrounding Brexit

Brexit supporters see this as being key to avoiding the backstop.

However, a government commitment to seek alternative arrangements by the end of 2020 is not new - it was laid out in a joint statement with the EU in March, external.

The prime minister also said that if the backstop was applied and Northern Ireland had to continue to follow EU rules, then the rest of the UK would voluntarily follow those same rules.

That is also not new - it was part of a package of commitments, external announced by the UK government almost six months ago.

However, the government would claim that moving from political promises to legally binding commitments should be seen as significant.

Wield its veto

What was new in the prime minister's speech was the role that Stormont would play if the backstop was ever implemented.

In January, the UK government said that if any new areas of Northern Ireland-specific alignment were to be added to the backstop, then it would "seek the agreement of the Northern Ireland Assembly".

NI's devolved government collapsed in January 2017 following a bitter dispute between Sinn Féin and the DUP

That stopped well short of a Stormont veto - Westminster was only required to seek agreement, not to get it.

This has now been toughened up.

The prime minister said: "The Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive will have to give their consent on a cross-community basis for new regulations which are added to the backstop."

The words "cross-community basis" are important as it means that a simple majority vote of the assembly would not be enough.

It is possible that unionists, who dislike the very concept of the backstop, could use a blocking mechanism known as the petition of concern.

What would happen if Stormont did veto any addition to the backstop is not entirely clear.

All we can say for sure is that there is a mechanism in the Withdrawal Agreement that ultimately allows the EU to take "appropriate remedial measures" if the UK does not update the backstop.

There is also the question of how to define a new regulation - under the Withdrawal Agreement a regulation is not new if it is replacing or amending an existing regulation.

So it is likely that Stormont would only, very rarely, get an opportunity to wield its veto.

- Published21 May 2019

- Published21 May 2019

- Published21 May 2019

- Published13 July 2020

- Published26 January 2024

- Published16 October 2019