Belfast City Cemetery: 150 years of buried stories

- Published

On 4 August 1869, the body of three-year-old Annie Collins was lowered into her paupers' grave in what was the very first burial at Belfast Cemetery, later to be known as Belfast City Cemetery.

Exactly 150 years later, her once solitary plot is surrounded by more than 226,000 others.

The abundant wealth of some of those buried in the cemetery's grounds is clear from the beautifully carved monuments and ornamental gates that surround their remains.

Others, like Annie's parents, were too poor to afford a simple headstone.

Annie's short life and hundreds of others like her are only remembered thanks to the work of historians who have, over the years, meticulously poured through public records to uncover their fascinating stories.

In a few months, Belfast City Council will begin a Heritage Lottery-funded restoration project to restore the cemetery to its previous glory.

The great wealth of some of those who rest in Belfast City Cemetery is displayed in beautifully carved statues and monuments

Author and historian Tom Hartley, who leads guided tours of the cemetery, says the graveyard "sums up the history of Belfast at the height of its power and wealth".

"All the big industrialists are buried here in this ground, alongside those who worked for them and in some cases died for them," he tells BBC News NI.

The Victorian 'big hitters'

It has been said many times that death is a great leveller, but this cemetery highlights the hierarchical systems and sexism that thrived in Victorian cities.

It is no coincidence that some of the most prominent Belfast families of the 19th and 20th centuries lie in raised vaults at the top of the central steps overlooking the vast graveyard below.

The graves of Sir Edward Harland and Thomas Gallaher lie in raised vaults at the top of the central steps

Sir Edward Harland, co-founder of the shipbuilding company Harland and Wolff, lies alongside tobacco merchant Thomas Gallaher, a man caustically described by Mr Hartley as "the greatest serial killer of all time".

Ironically, today these once impressive graves are overrun by weeds and surrounded by an ugly wrought iron fence for health and safety purposes, while those less fortunate, whose graves lie in less ostentatious surroundings, are often tended to by strangers.

Nearby is Viscount William Pirrie, former chair of Harland and Wolff. In the months leading up to the Titanic disaster, Lord Pirrie was questioned about the number of life boats aboard his ships.

He responded that the ships were unsinkable and the rafts were to save others, a line that would haunt him to his death in 1924.

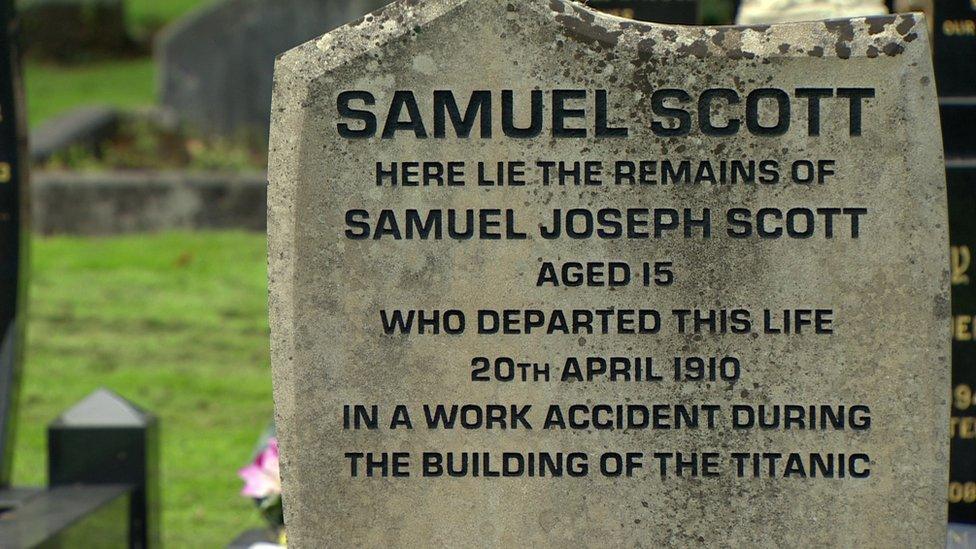

Further down the densely populated 100 acre plot of land, there lies a more understated grave, that of 15-year-old Samuel Scott, the first worker to die in the building of the Titanic.

In 1910, 15-year-old Samuel Scott became the first worker to die in the building of the Titanic

He was a so-called catch boy, who collected rivets, but fell to his death from the side of the ill-fated ship while under construction.

Samuel's descendants later told Mr Hartley that representatives of the shipbuilding giant later offered his family 12 shillings as compensation for the loss of their son.

His parents were also too poor to mark where he lay, but in 2011, a headstone was unveiled as part of the Féile an Phobail festival.

"So you see in just a few of the many graves here that Belfast was a schizophrenic sort of city, with enormous wealth and abject poverty," Mr Hartley says.

Radical

It was also, he adds, a city where Catholics converted to Protestantism and Presbyterians became Irish republicans.

A case in point is Robert Lynd, the son of a Presbyterian moderator, who was educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, now known as Inst, who later became an Irish republican writer.

Guide Tom Hartley at the grave of Robert Lynd, the son of a Presbyterian moderator, who became an Irish republican writer

"Robert taught Roger Casement how to speak Irish. He wrote the introduction to James Connolly's pamphlet, Labour in Irish History. He was a friend of James Joyce and when Joyce married Nora Barnacle, they stayed with Robert," says Mr Hartley.

"The cemetery is a great reminder that the political and cultural identity of late 19th century Belfast was complex and layered."

What about the women?

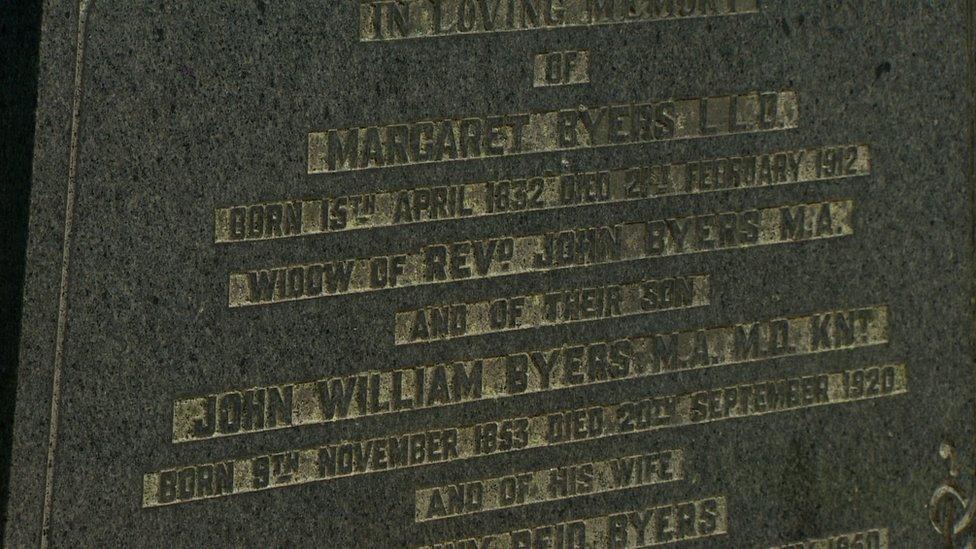

Mr Hartley says women buried in the cemetery were defined by the men they married.

The headstone of Margaret Byers, a renowned educationalist, activist and social reformer who founded Belfast's Victoria College for girls, simply describes her as "the widow of Rev John Byers", her husband who died about 50 years earlier.

Margaret Byers founded Belfast girls' school Victoria College

"It says nothing about what she achieved in her life," says Mr Hartley.

Behind a nearby oak tree lies a small patch of land, surrounded by an iron fence, with a sign that reads Ulster Female Penitentiary.

This is the unmarked grave of seven women who experienced unimaginable hardship, Mr Hartley explains.

"These women would have been labelled as prostitutes, and as such, we're not meant to know they're even here."

In a small grave with a simple iron sign that reads Ulster Female Penitentiary lie seven women

"These women epitomise our need to understand history, because we need to know who they were and how they were treated and the circumstances that brought them to the penitentiary."

Margaret Byers and her friend Isabella Todd - a Scottish suffragist who is buried in south Belfast's Balmoral cemetery - campaigned to help prostitutes and all exploited women by opposing the Contagious Diseases Act, legislation that allowed for the arrest of women suspected of being prostitutes.

Grieving parents

The grief of those who were left behind is evident in some of the more ornate monuments.

The grave of 14-year-old George Sayers, the only son of wealthy landowners in Malone Heights, who died in a sporting accident, is particularly poignant.

The headstone of 14-year-old George Sayers, the only son of wealthy landowners in Malone Heights, who died in a sporting accident

"In the roundel, you see two rose flowers in bloom, then you see a sickle, and beneath it, a rose bud broken at its stem," Mr Hartley points out.

"The two roses represent George's parents, the sickle is the grim reaper and the broken rose bud is George - he never got a chance to fully bloom."

- Published29 October 2018

- Published17 April 2012