Leprechaun 'is not a native Irish word' new dictionary reveals

- Published

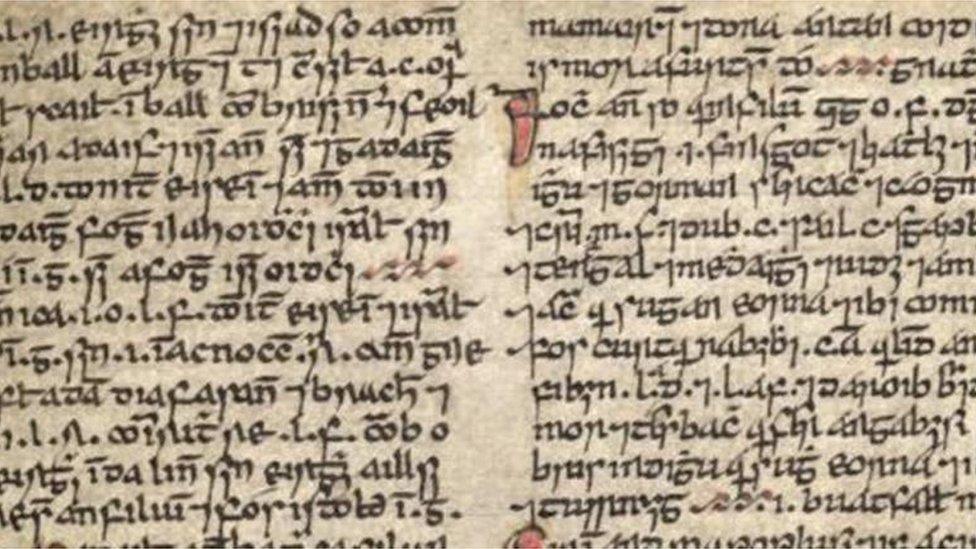

A painstaking journey through Irish manuscripts has yielded great rewards

Leprechauns may be considered quintessentially Irish, but research suggests this perception is blarney.

The word "leprechaun" is not a native Irish one, scholars have said.

They have uncovered hundreds of lost words from the Irish language and unlocked the secrets of many others.

Although "leipreachán" has been in the Irish language for a long time, researchers have said it comes from Luperci, a group linked to a Roman festival.

The feast included a purification ritual involving swimming and, like the Luperci, leprechauns are associated with water in what may be their first appearance in early Irish literature.

According to an Old Irish tale known as The Adventure of Fergus son of Léti, leprechauns carried the sleeping Fergus out to sea.

The team from Queen's and Cambridge spent five years studying old manuscripts and texts

A new revised dictionary created from the research spans 1,000 years of the Irish language from the 6th to the 16th Centuries.

A team of five academics from Cambridge University and Queen's University Belfast carried out painstaking work over five years, scouring manuscripts and texts for words which have been overlooked or mistakenly defined.

Their findings can now be freely accessed in the revised version of the online dictionary of medieval Irish, external.

An 'ogach' or 'eggy' place was considered just right for setting up home in medieval Ireland

Among the words brought back to life in this project are "ogach", which means "eggy" - but in a good way: If you were choosing where to live in medieval Ireland you would want somewhere ogach - "abounding in eggs".

On the other hand it is probably bad news if you hear the word "brachaid", meaning: "It oozes pus."

The scholars discovered other quirky words, such as "séis" - an old Irish word for a six-day week.

The dictionary of medieval Irish is 23 volumes long. It spans a period from 700 to 1700.

For Professor Greg Toner from Queen's University Belfast, finding and documenting the words has been a labour of love spanning nearly 20 years.

Academics have uncovered about 500 lost words in the Irish language

"People think it is an old language and there are no new words, but our interpretation changes," he said.

"We found about 500 words that have not been recorded. Among them is the word "séis", which means a period of six days.

"This is great, if you can't be bothered working a full week."

Other words include the Irish for curlew - "crottach" or "the humped one" - and might be an allusion to the bird's distinctive beak.

The old Irish word for curlew is "crottach"

The resource is a full academic dictionary with scholarly references and it already reaches a wide audience.

Prof Toner said the web version attracts 20,000 users a month - about a third from Ireland, a third from America and a third from the rest of the world.

"A key aim of our work has been to open the dictionary up, not only to students of the language but to researchers working in other areas such as history and archaeology, as well as to those with a general interest in medieval life," he said.

The resource allows users to put in any word to discover what the old Irish word was.

You can find the first reference to potato and how many different words there were for a knife or a sword.

Máire Ní Mhaonaigh, professor of Celtic and medieval studies at Cambridge, said the dictionary offered "real insight into the past and into how people lived".

The modern Irish word for computer dates back from a long time before they were invented

Some words suggest that the medieval world still resonates, she said.

One of these is "rímaire", the modern Irish word for computer (in its later form ríomhaire).

"In the medieval period, rímaire referred not to a machine but to a person engaged in the medieval science of computistics who performed various kinds of calculations concerning time and date, most importantly the date of Easter.

"So it's a word with a long pedigree whose meaning was adapted and applied to a modern invention."

The researchers are also developing educational resources for schools in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.