Ivor Bell: What is a trial of the facts?

- Published

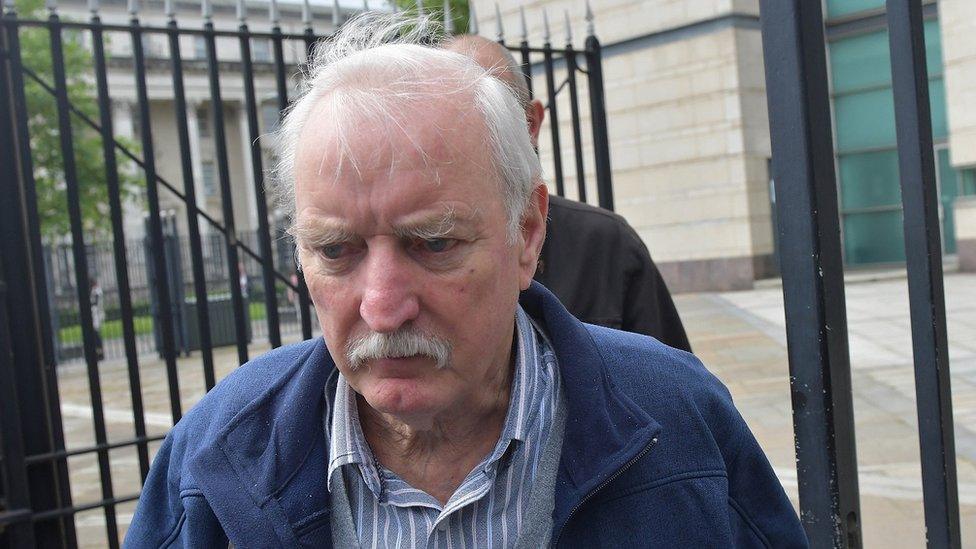

Ivor Bell, a former IRA leader, has been cleared of soliciting one of the most notorious murders of the Troubles after a trial of the facts.

The trial had heard allegations that Gerry Adams recommended the murder and secret burial of Jean McConville, one of the Disappeared, in 1972.

The case against 82-year-old Mr Bell was based on alleged admissions made to a Boston College oral history project which were played in public for the first time during the legal action.

The judge ruled the tapes were unreliable and could not be used as evidence against him.

The case was heard as a trial of the facts.

What is a trial of the facts?

If, based on medical evidence, a court determines that a person is unfit to stand trial, then criminal proceedings cannot proceed.

Prosecutors, however, have the option to have the matter heard as a "trial of the facts".

This process takes the place of a criminal trial. It is a public hearing to determine whether an accused committed the acts alleged.

It cannot result in a conviction, but if the court is not satisfied that the accused committed the acts alleged, then he/she will be acquitted.

The procedure is allowed for in legislation by Article 49A of the Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order 1986.

What happens during a trial of the facts?

The prosecution puts its evidence against the defendant before a judge and jury, in a courtroom, in a similar way to a normal criminal trial.

However, the accused does not play a part in proceedings as such. They do not necessarily even need to be in court.

The accused will be represented by a legal team and their lawyers can question the witnesses, challenge the evidence and make legal submissions on their behalf.

Unlike in a criminal trial, the jury is not required to return a verdict of guilty or not guilty.

Ivor Bell, 83, was cleared of two counts of soliciting the murder of Jean McConville

Instead, they are asked to decide whether or not the accused committed the offence with which they were charged.

The focus is on what they are alleged to have physically done - not their state of mind at the time.

In a normal criminal trial, a jury would be invited to decide whether or not a defendant had the mental faculties required to be guilty of the offence as well.

The standard of proof remains the same - a jury must be sure beyond all reasonable doubt that the accused committed the acts alleged.

The accused can't be convicted but they can be acquitted if the jury decide they didn't commit the acts alleged.

What happens if it is found an accused committed the offence?

The court will not sentence them as normal - but instead has the option of making a number of treatment orders, or an absolute discharge.

A number of different medical orders are available to the judge in the place of sentencing, as set out by legislation. These are mainly designed to protect the public.

An individual can be committed to hospital, they can be subject to a guardianship order or they can be subject to a supervision and treatment order.

If none of those are required, the defendant would be absolutely discharged.

Being absolutely discharged means the defendant committed the offence, but there is no punishment or order of any substance. They are free to go.