Coronavirus: Living through a pandemic without sound

- Published

For the deaf community, the pandemic has brought a new set of challenges.

Support services have been disrupted and communicating is more difficult when people are wearing masks.

There are about 300,000 people in Northern Ireland affected by hearing loss.

BBC News NI spoke to some of them about their experiences during the coronavirus outbreak.

Leanne Gillespie was provided with technology to map her daughter's cochlear implants at home

Harnessing technology

Leanne Gillespie's 20-month-old daughter Ella-May was born profoundly deaf and had cochlear implants fitted in January.

They needed to attend four mapping appointments to have them programmed, but when lockdown was brought in those appointments could not happen.

Mrs Gillespie was told she would have to conduct the mapping herself at home via video call.

She said: "We've been provided with a tablet which the audiologist has access to from her own home and when we connect Ella-May's processors to the tablet during the video call, the audiologist can then play different frequencies of sounds to Ella-May and observe her reaction through the video call.

"We as parents were delighted this option was available and the medical team in Beech Hall Implant Centre have been brilliant at keeping in contact to catch up on Ella-May's progress."

There are about 4,500 British Sign Language users and 1,500 Irish Sign Language users in Northern Ireland.

Last month, members of the deaf community campaigned for a remote video interpreting service for the NHS 111 helpline.

In the rest of the UK, the service is accompanied by an online sign language relay service, so deaf people can use the number.

Northern Ireland was given access to the helpline at the end of February, but the video relay service and an interpreting system was only brought in at the end of April.

Communication barriers

Adrian and Victoria Richardson's seven-year-old son Emmett was born profoundly deaf and had cochlear implants fitted after a year of hearing aid tests.

He attends a primary school with a Hearing Impairment Unit attached where he has daily speech therapy and is taught in a classroom that is adapted for children with hearing aids or implants.

Mr Richardson said it was a big worry when his son's school closed as he is "more relaxed and confident around children on the same level as him".

Adrian Richardson worried that his son Emmett would find home schooling difficult

"We were worried if he'd be able to learn the same way they do it in the classroom, you're afraid of doing it wrong," he said.

"Everything for him is visual, he loves to be communicating and he loves to be around his friends.

"At the start he didn't understand it. I ended up drawing a picture of a person being sick and then going on a plane to create visuals of what coronavirus meant.

"He watches the news and asks us, 'what did they say?' and we'll sign it to him."

PPE problems

Mr and Mrs Richardson recently took their son to a hospital appointment but had difficulty communicating with doctors and nurses wearing personal protective equipment (PPE), as this meant Emmett could not lip read.

"Emmett kept trying to show them sign language, but the doctors were very apologetic as he was the first deaf person they'd had in the clinic," he said.

"He had to keep his mask on and his mum had to translate what the doctors were saying."

Emmett joins weekly video call activities organised by Action Deaf Youth, a charity that connects young people with hearing impairments.

They provided the children with videos on different sign language they could use that relates to the virus to help them learn more about it.

"It's kept them all connected and it's something to look forward to," Mr Richardson said.

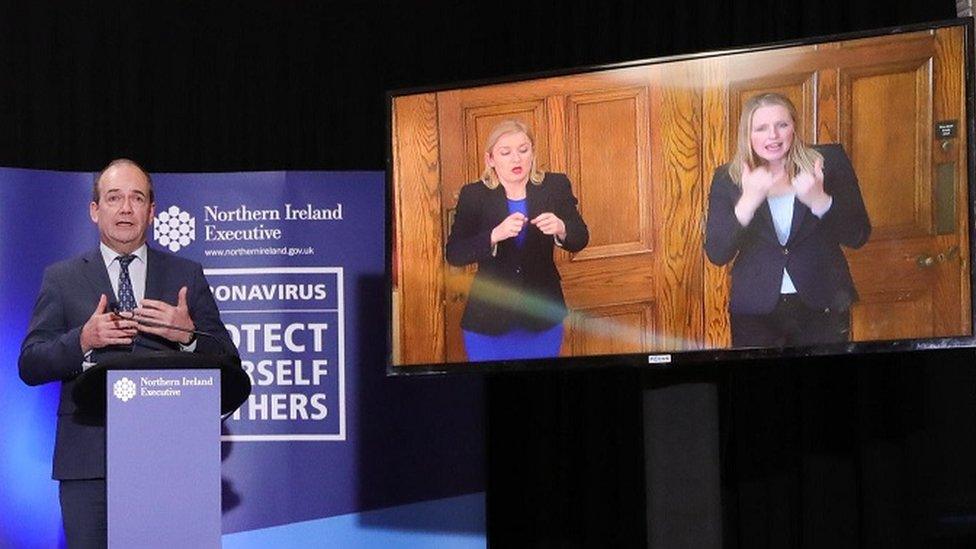

Sign language interpreters Amanda Coogan and Kristina Sinclair (top left corner) sign at the Stormont briefings

People in Northern Ireland have been recommended to wear face coverings, external "for short periods in enclosed spaces, where social distancing is not possible", such as shops and public transport.

Majella McAteer, of the NI branch of the British Deaf Association, said that if mask-wearing becomes compulsory for everyone, it would "become extremely trying for a deaf person".

"A big part of sign language is facial expressions and lip patterns so to lose these pieces leaves it much more difficult to communicate," she said.

"A full-face shield works better for a deaf person, but unfortunately these are most often used in conjunction with a surgical mask.

"There are masks known as communicator masks which have a window to allow the lips to be seen, but there are very few medical professionals with access to these."

Ms McAteer said that the lockdown has been isolating for the deaf community and accessing information has been difficult.

She added that deaf people often use sign language as their first and preferred language, with English being a second and even sometimes third language.

"Imagine trying to understand some of the concepts around coronavirus and social distancing in a foreign language if you only have a basic GCSE level grasp of that language," she said.

- Published29 April 2020