Coronavirus: Covid-19 samples tested in Belfast laboratory

- Published

Dr Ultan Power described it as "significant" that they can examine the virus in a Belfast laboratory

Scientists at Queen's University in Belfast are working with Covid-19 samples to identify potential drugs that could save lives around the world.

The UK-wide research involves the Queen's team screening in the region of 1,200 different drugs in various combinations that will either kill the virus or stop it from replicating.

The samples were shipped from Public Health England via lorry and road.

They were contained in a vial a little bigger than a thimble.

Dr Lindsay Broadbent, a research fellow in virology, told BBC News NI that depending on its concentration, the vial's contents could infect hundreds or thousands of people.

"It was shipped by a company that specialises in this transportation," she said.

"The virus was contained in a vial which was placed within a container which itself was in another container and that was surrounded by absorption paper and then surrounded by dry ice to keep it frozen and all of that would have been in a very large polystyrene box.

"It was extremely safe."

Dr Lindsay Broadbent says the way the virus samples were transported was "extremely safe"

The project is highly significant as it is using clinically-proven drugs that can be repurposed in order tackle Covid-19.

That should speed up the process, as discovering a new drug from scratch can take years.

'Risk is minimal'

Dr Ultan Power, a professor of molecular virology at Queen's, said: "It is one of the few projects in the UK that is funded by the UK Research and Innovation to look at repurposing drugs that have already been approved for human use against the virus.

"We are looking at an antiviral aspect that can prevent the virus from causing infection in the cells and also the anti-inflammatory response, which is the immune system's response to the infection that in very severe cases causes a lot more of the damage than the actual virus itself."

The scientists and their colleague Dr Connor Bamford are used to working in high-risk areas.

Dr Broadbent said: "Yes, this is just our day job, all we care about is doing good science.

"It doesn't matter what virus we are looking at and there are always risks involved, but as long as we follow the protocols in how we were trained then the risk is minimal."

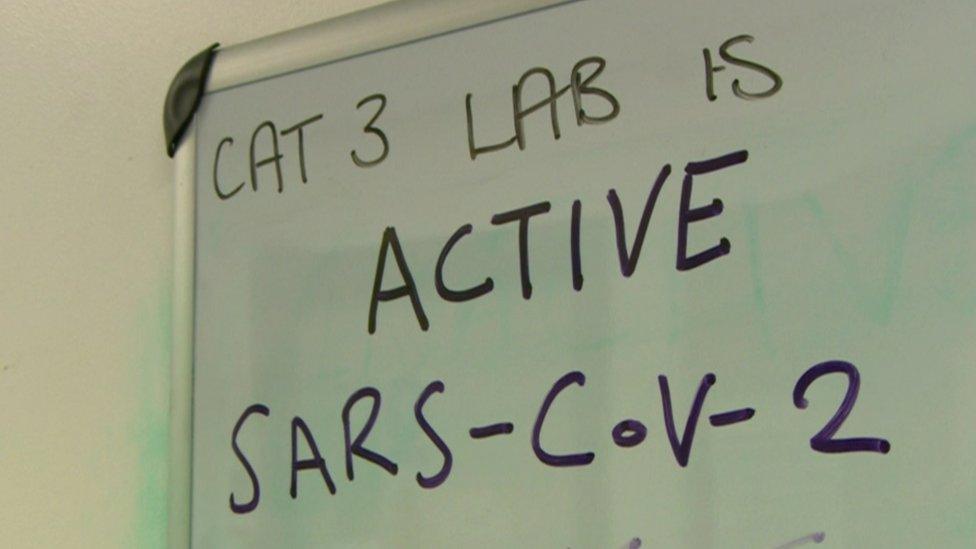

The research team is carrying out its tests in "a lab within a lab" to ensure a secure environment

The crucial part of the work takes place in a highly secure biosafety level three area, described by Dr Broadbent as "a lab within a lab".

She said: "Within that there is a negative pressure system that means all the airflow goes into the lab which means there is never any airflow from the lab into the corridor and that's primarily what keeps us safe.

"Then within that inner lab there is a biosafety cabinet and that is where we work with the virus which provides another level of protection because all of that air within the lab is kept there and is then extracted up through the ceiling and out through filters. "

Analysis

By Marie-Louise Connolly, BBC News NI Health Correspondent

So what is it like sharing a lab with a deadly virus?

In reality, I was at least 15ft away from the sample of Covid-19 and protected by two thick windows.

My cameraman Niall Gallagher and I were told the filming would take place in a biosafety level three lab - one where research is done "using agents that are associated with serious or lethal human disease".

A risk assessment and all the necessary checks were done before travelling to the Queen's science labs, where we got changed into our white coats, masks and visors.

From our positions in the corridor we looked on as Dr Lindsay Broadbent changed into full PPE inside the first lab or contained area.

The door to a second lab was then opened and inside further safety precautions were carried out.

Donning goggles, then an FFP3 mask which was personally fitted and tested to ensure it is completely sealed, Dr Broadbent moves between fridges and the hood.

The area is small, hot and soon clearly uncomfortable.

The drab surroundings fail to match the importance of what's going on under the hood.

A sample of Covid-19 which has killed 500,000 worldwide is in the gloved hands of Dr Broadbent under the hood and only metres away. The small flask-like container is moved slowly and carefully about.

It is not at all the way I imagined.

But what I was witnessing was part of a global effort to save lives by finding a way of killing the virus.

Real progress

Dr Power said it is significant that they are handling the virus.

"That's real progress. To have it here in this lab to handle it (through the best personal protective equipment) we are able to see what it does to cells now and to see the damage that it is causing. "

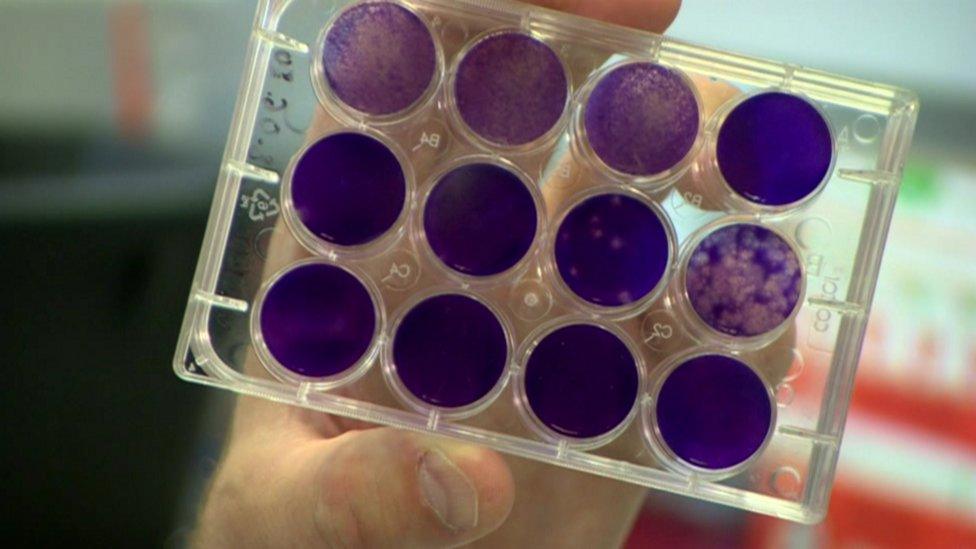

Dr Power showed slides in which white "holes" highlight the damage that the virus does to cells.

"So when we are screening particular drugs we would be looking to see how the cells react to the drugs and that gives us an indication as to whether we have something that might be useful against Sars-Cov-2, " he said.

Dr Broadbent would like to be able to publish results by the end of the year.

"Realistically we don't really know when that is going to be - there are lots of factors involved and it really does depend how well the research goes."

- Published27 May 2020