Brexit: What does a trade deal mean for Northern Ireland?

- Published

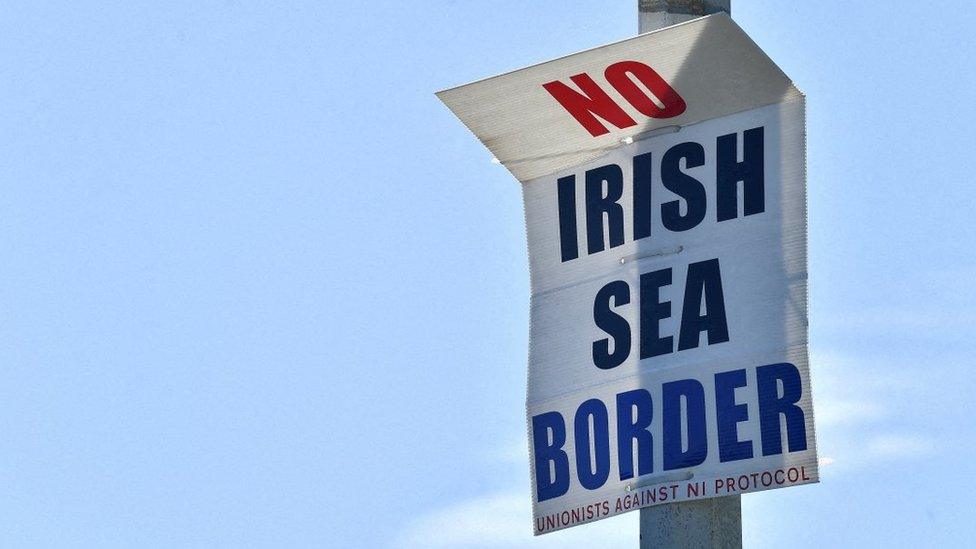

A trade deal will help solve some of the problems created by the new Irish Sea border.

But on its own it would not solve them all.

The EU and UK already have a deal on Northern Ireland.

It's called the Northern Ireland protocol and formed part of last year's withdrawal agreement.

It's fundamental purpose is to prevent a hardening of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

It does that by keeping Northern Ireland in the EU's single market for goods and by having Northern Ireland apply EU customs rules at its ports.

That means goods arriving from Great Britain are supposed to be checked and controlled at Northern Ireland's ports from 1 January.

The implementation of the protocol is the subject of a separate negotiation between the EU and UK, through a body called the Joint Committee

But the work of the Joint Committee is easier with a trade deal.

The direct impact of a trade deal?

One of the most difficult issues facing the Joint Committee is "at risk" goods.

These are goods which the EU fear could travel from Great Britain through Northern Ireland, on into the Republic and the wider EU without paying the correct EU tariff.

In other words, Northern Ireland could become a tariff-dodgers backdoor into the EU's customs union.

Northern Ireland will have to enforce EU customs rules at its ports when the Brexit transition period ends on 1 January

The solution is that some goods will be deemed at risk and hit with a EU tariff as they enter NI from GB.

The tariff could be rebated if it could be shown the goods were consumed in NI.

This would create a new layer of complexity and expense on GB-NI trade and is politically controversial.

The Joint Committee is supposed to agree what goods are at risk, with the UK keen for a more permissive approach than the EU.

But with a trade deal, which eliminates tariffs on all goods, then the at risk goods issue is hugely reduced.

If there are no tariffs then there is no risk.

However, as the customs expert Anna Jerzewska explains the issue does not go away entirely because of rules of origin.

That means that GB goods would have to show they really are GB goods and therefore qualify for the zero tariff treatment.

The indirect impacts of a trade deal

A trade deal by itself does not solve some of the trickiest issues facing the Joint Committee.

It will not change the fact that Northern Ireland will stay in the EU's single market for goods while the rest of the UK leaves.

For example, businesses shipping food products from GB to NI are set to face onerous new bureaucracy as a result of this arrangement.

Supermarket chain Sainsbury's has already issued a warning about the availability of some foods in NI

But a trade deal could create the good will which allows some of these Irish Sea border issues to be mitigated.

When it comes to the food products issues the supermarkets have put forward a plan for a form of "trusted trader" scheme which reduce the levels of new checks and controls.

Some in the business community think the EU has been reluctant to move on these issues because Northern Ireland has been drawn into the trade talks.

Last month, Aodhán Connolly from the NI Retail Consortium told MPs it appeared the work of the Joint Committee had being slowed down by the "political machinations" of the trade talks.

"What we feel is happening at the moment is the political effort is going into the free trade agreement and because of that neither side wants to give flexibilities on Northern Ireland because it can be seen as leverage," he said.

He expressed hope that with a trade deal, the talks on Northern Ireland issues can be intensified.

Related topics

- Published5 December 2020

- Published1 December 2020

- Published1 January 2021

- Published2 February 2024